Related Research Articles

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

An antibody (Ab) is the secreted form of a B cell receptor; the term immunoglobulin (Ig) can refer to either the membrane-bound form or the secreted form of the B cell receptor, but they are, broadly speaking, the same protein, and so the terms are often treated as synonymous. Antibodies are large, Y-shaped proteins belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which are used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that cause disease. Antibodies can recognize virtually any size antigen with diverse chemical compositions from molecules. Each antibody recognizes one or more specific antigens. Antigen literally means "antibody generator", as it is the presence of an antigen that drives the formation of an antigen-specific antibody. Each tip of the "Y" of an antibody contains a paratope that specifically binds to one particular epitope on an antigen, allowing the two molecules to bind together with precision. Using this mechanism, antibodies can effectively "tag" a microbe or an infected cell for attack by other parts of the immune system, or can neutralize it directly.

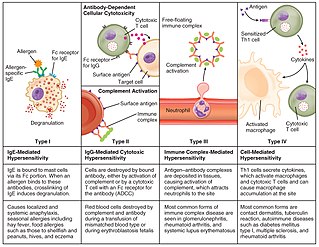

Hypersensitivity is an abnormal physiological condition in which there is an undesirable and adverse immune response to antigen. It is an abnormality in the immune system that causes immune diseases including allergies and autoimmunity. It is caused by many types of particles and substances from the external environment or from within the body that are recognized by the immune cells as antigens. The immune reactions are usually referred to as an over-reaction of the immune system and they are often damaging and uncomfortable.

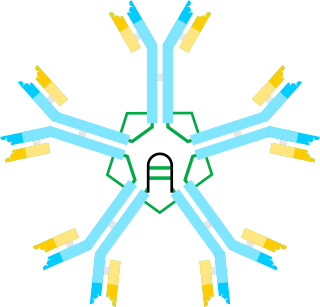

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) is the largest of several isotypes of antibodies that are produced by vertebrates. IgM is the first antibody to appear in the response to initial exposure to an antigen; causing it to also be called an acute phase antibody. In humans and other mammals that have been studied, plasmablasts in the spleen are the main source of specific IgM production.

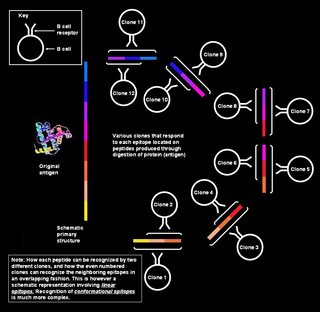

An epitope, also known as antigenic determinant, is the part of an antigen that is recognized by the immune system, specifically by antibodies, B cells, or T cells. The part of an antibody that binds to the epitope is called a paratope. Although epitopes are usually non-self proteins, sequences derived from the host that can be recognized are also epitopes.

The complement system, also known as complement cascade, is a part of the immune system that enhances (complements) the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to clear microbes and damaged cells from an organism, promote inflammation, and attack the pathogen's cell membrane. It is part of the innate immune system, which is not adaptable and does not change during an individual's lifetime. The complement system can, however, be recruited and brought into action by antibodies generated by the adaptive immune system.

The direct and indirect Coombs tests, also known as antiglobulin test (AGT), are blood tests used in immunohematology. The direct Coombs test detects antibodies that are stuck to the surface of the red blood cells. Since these antibodies sometimes destroy red blood cells they can cause anemia; this test can help clarify the condition. The indirect Coombs test detects antibodies that are floating freely in the blood. These antibodies could act against certain red blood cells; the test can be carried out to diagnose reactions to a blood transfusion.

Opsonins are extracellular proteins that, when bound to substances or cells, induce phagocytes to phagocytose the substances or cells with the opsonins bound. Thus, opsonins act as tags to label things in the body that should be phagocytosed by phagocytes. Different types of things ("targets") can be tagged by opsonins for phagocytosis, including: pathogens, cancer cells, aged cells, dead or dying cells, excess synapses, or protein aggregates. Opsonins help clear pathogens, as well as dead, dying and diseased cells.

Antibody opsonization is a process by which a pathogen is marked for phagocytosis.

Immunogenicity is the ability of a foreign substance, such as an antigen, to provoke an immune response in the body of a human or other animal. It may be wanted or unwanted:

An immune complex, sometimes called an antigen-antibody complex or antigen-bound antibody, is a molecule formed from the binding of multiple antigens to antibodies. The bound antigen and antibody act as a unitary object, effectively an antigen of its own with a specific epitope. After an antigen-antibody reaction, the immune complexes can be subject to any of a number of responses, including complement deposition, opsonization, phagocytosis, or processing by proteases. Red blood cells carrying CR1-receptors on their surface may bind C3b-coated immune complexes and transport them to phagocytes, mostly in liver and spleen, and return to the general circulation.

Co-stimulation is a secondary signal which immune cells rely on to activate an immune response in the presence of an antigen-presenting cell. In the case of T cells, two stimuli are required to fully activate their immune response. During the activation of lymphocytes, co-stimulation is often crucial to the development of an effective immune response. Co-stimulation is required in addition to the antigen-specific signal from their antigen receptors.

Protein A is a 42 kDa surface protein originally found in the cell wall of the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus. It is encoded by the spa gene and its regulation is controlled by DNA topology, cellular osmolarity, and a two-component system called ArlS-ArlR. It has found use in biochemical research because of its ability to bind immunoglobulins. It is composed of five homologous Ig-binding domains that fold into a three-helix bundle. Each domain is able to bind proteins from many mammalian species, most notably IgGs. It binds the heavy chain within the Fc region of most immunoglobulins and also within the Fab region in the case of the human VH3 family. Through these interactions in serum, where IgG molecules are bound in the wrong orientation, the bacteria disrupts opsonization and phagocytosis.

Complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) are polypeptide segments of the variable chains in immunoglobulins (antibodies) and T cell receptors, generated by B-cells and T-cells respectively. CDRs are where these molecules bind to their specific antigen and their structure/sequence determines the binding activity of there respective antibody. A set of CDRs constitutes a paratope, or the antigen-binding site. As the most variable parts of the molecules, CDRs are crucial to the diversity of antigen specificities generated by lymphocytes.

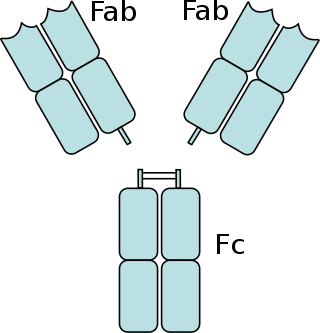

The fragment crystallizable region is the tail region of an antibody that interacts with cell surface receptors called Fc receptors and some proteins of the complement system. This region allows antibodies to activate the immune system, for example, through binding to Fc receptors. In IgG, IgA and IgD antibody isotypes, the Fc region is composed of two identical protein fragments, derived from the second and third constant domains of the antibody's two heavy chains; IgM and IgE Fc regions contain three heavy chain constant domains in each polypeptide chain. The Fc regions of IgGs bear a highly conserved N-glycosylation site. Glycosylation of the Fc fragment is essential for Fc receptor-mediated activity. The N-glycans attached to this site are predominantly core-fucosylated diantennary structures of the complex type. In addition, small amounts of these N-glycans also bear bisecting GlcNAc and α-2,6 linked sialic acid residues.

Polyclonal B cell response is a natural mode of immune response exhibited by the adaptive immune system of mammals. It ensures that a single antigen is recognized and attacked through its overlapping parts, called epitopes, by multiple clones of B cell.

Type III hypersensitivity, in the Gell and Coombs classification of allergic reactions, occurs when there is accumulation of immune complexes that have not been adequately cleared by innate immune cells, giving rise to an inflammatory response and attraction of leukocytes. There are three steps that lead to this response. The first step is immune complex formation, which involves the binding of antigens to antibodies to form mobile immune complexes. The second step is immune complex deposition, during which the complexes leave the plasma and are deposited into tissues. Finally, the third step is the inflammatory reaction, during which the classical pathway is activated and macrophages and neutrophils are recruited to the affected tissues. Such reactions may progress to immune complex diseases.

Immune adherence was described by Nelson (1953) for an in vitro immunological reaction between normal erythrocytes and a wide variety of microorganisms sensitized with their individually specific antibody and complement; erythrocytes were observed to adhere to microorganisms. It was later recognized to occur in vivo.

A neutralizing antibody (NAb) is an antibody that defends a cell from a pathogen or infectious particle by neutralizing any effect it has biologically. Neutralization renders the particle no longer infectious or pathogenic. Neutralizing antibodies are part of the humoral response of the adaptive immune system against viruses, intracellular bacteria and microbial toxin. By binding specifically to surface structures (antigen) on an infectious particle, neutralizing antibodies prevent the particle from interacting with its host cells it might infect and destroy.

Antigen-antibody interaction, or antigen-antibody reaction, is a specific chemical interaction between antibodies produced by B cells of the white blood cells and antigens during immune reaction. The antigens and antibodies combine by a process called agglutination. It is the fundamental reaction in the body by which the body is protected from complex foreign molecules, such as pathogens and their chemical toxins. In the blood, the antigens are specifically and with high affinity bound by antibodies to form an antigen-antibody complex. The immune complex is then transported to cellular systems where it can be destroyed or deactivated.

References

- 1 2 3 Anderson DM, ed. (2003). "Sensitization." Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary , 30th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, p. 1680. ISBN 0-7216-0146-4.

- 1 2 3 Brown MJ, ed. (1992). "Sensitization." Miller-Keane Encyclopedia & Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health , 5th ed. Philadelphia; London: Saunders, p. 1352. ISBN 0-7216-3456-7.

- 1 2 Pugh MB, ed. (2000). "Sensitization." Stedman's Medical Dictionary , 27th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, p. 1619. ISBN 0-683-40007-X.

- 1 2 3 Janeway C, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik M, eds. (2001). Immunobiology 5: The Immune System in Health and Disease. New York: Garland Pub., ISBN 0-8153-3642-X

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tada T, Taniguchi M, Okumura Y, Miyasaka M, eds. (1993). "Sensitization." Dictionary of Terms in Immunology, 3rd ed. Osaka: Saishin-Igakusha, Ltd., p. 510. ISBN 4-914909-10-3 C3547 (in Japanese).