Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized silicate grains, cemented together by another mineral. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

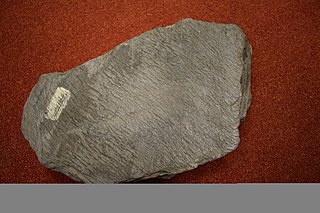

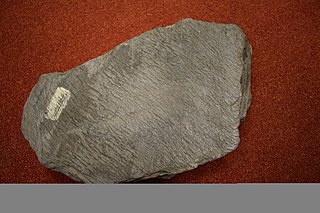

Schist is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes or plates. This texture reflects a high content of platy minerals, such as mica, talc, chlorite, or graphite. These are often interleaved with more granular minerals, such as feldspar or quartz.

Phyllite is a type of foliated metamorphic rock formed from slate that is further metamorphosed so that very fine grained white mica achieves a preferred orientation. It is primarily composed of quartz, sericite mica, and chlorite.

Petrography is a branch of petrology that focuses on detailed descriptions of rocks. Someone who studies petrography is called a petrographer. The mineral content and the textural relationships within the rock are described in detail. The classification of rocks is based on the information acquired during the petrographic analysis. Petrographic descriptions start with the field notes at the outcrop and include macroscopic description of hand-sized specimens. The most important petrographer's tool is the petrographic microscope. The detailed analysis of minerals by optical mineralogy in thin section and the micro-texture and structure are critical to understanding the origin of the rock.

Metasomatism is the chemical alteration of a rock by hydrothermal and other fluids. It is traditionally defined as metamorphism which involves a change in the chemical composition, excluding volatile components. It is the replacement of one rock by another of different mineralogical and chemical composition. The minerals which compose the rocks are dissolved and new mineral formations are deposited in their place. Dissolution and deposition occur simultaneously and the rock remains solid.

Hornfels is the group name for a set of contact metamorphic rocks that have been baked and hardened by the heat of intrusive igneous masses and have been rendered massive, hard, splintery, and in some cases exceedingly tough and durable. These properties are caused by fine grained non-aligned crystals with platy or prismatic habits, characteristic of metamorphism at high temperature but without accompanying deformation. The term is derived from the German word Hornfels, meaning "hornstone", because of its exceptional toughness and texture both reminiscent of animal horns. These rocks were referred to by miners in northern England as whetstones.

The chlorites are the group of phyllosilicate minerals common in low-grade metamorphic rocks and in altered igneous rocks. Greenschist, formed by metamorphism of basalt or other low-silica volcanic rock, typically contains significant amounts of chlorite.

Volcanogenic massive sulfide ore deposits, also known as VMS ore deposits, are a type of metal sulfide ore deposit, mainly copper-zinc which are associated with and produced by volcanic-associated hydrothermal events in submarine environments.

Sericite is the name given to very fine, ragged grains and aggregates of white (colourless) micas, typically made of muscovite, illite, or paragonite. Sericite is produced by the alteration of orthoclase or plagioclase feldspars in areas that have been subjected to hydrothermal alteration typically associated with copper, tin, or other hydrothermal ore deposits. Sericite also occurs as the fine mica that gives the sheen to phyllite and schistose metamorphic rocks.

The rock cycle is a basic concept in geology that describes transitions through geologic time among the three main rock types: sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous. Each rock type is altered when it is forced out of its equilibrium conditions. For example, an igneous rock such as basalt may break down and dissolve when exposed to the atmosphere, or melt as it is subducted under a continent. Due to the driving forces of the rock cycle, plate tectonics and the water cycle, rocks do not remain in equilibrium and change as they encounter new environments. The rock cycle explains how the three rock types are related to each other, and how processes change from one type to another over time. This cyclical aspect makes rock change a geologic cycle and, on planets containing life, a biogeochemical cycle.

Sedimentary exhalative deposits are zinc-lead deposits originally interpreted to have been formed by discharge of metal-bearing basinal fluids onto the seafloor resulting in the precipitation of mainly stratiform ore, often with thin laminations of sulfide minerals. SEDEX deposits are hosted largely by clastic rocks deposited in intracontinental rifts or failed rift basins and passive continental margins. Since these ore deposits frequently form massive sulfide lenses, they are also named sediment-hosted massive sulfide (SHMS) deposits, as opposed to volcanic-hosted massive sulfide (VHMS) deposits. The sedimentary appearance of the thin laminations led to early interpretations that the deposits formed exclusively or mainly by exhalative processes onto the seafloor, hence the term SEDEX. However, recent study of numerous deposits indicates that shallow subsurface replacement is also an important process, in several deposits the predominant one, with only local if any exhalations onto the seafloor. For this reason, some authors prefer the term clastic-dominated zinc-lead deposits. As used today, therefore, the term SEDEX is not to be taken to mean that hydrothermal fluids actually vented into the overlying water column, although this may have occurred in some cases.

This glossary of geology is a list of definitions of terms and concepts relevant to geology, its sub-disciplines, and related fields. For other terms related to the Earth sciences, see Glossary of geography terms.

Tonstein is a hard, compact sedimentary rock that is composed mainly of kaolinite or, less commonly, other clay minerals such as montmorillonite and illite. The clays often are cemented by iron oxide minerals, carbonaceous matter, or chlorite. Tonsteins form from volcanic ash deposited in swamps. Tonsteins occur as distinctive, thin, and laterally extensive layers in coal seams throughout the world. They are often used as key beds to correlate the strata in which they are found. The regional persistence of tonsteins and relict phenocrysts indicate that they formed as the result of the diagenetic alteration of volcanic ash falls in an acidic and low-salinity environment, consistent with a freshwater swamp. In contrast, the alteration of a volcanic ashfall deposit in a marine environment typically produces a bentonite layer.

Spilite is a fine-grained igneous rock, resulting particularly from alteration of oceanic basalt.

The Génis Unit is a Paleozoic metasedimentary succession of the southern Limousin and belongs geologically to the Variscan basement of the French Massif Central. The unit covers the age range Cambrian/Ordovician till Devonian.

Argillic alteration is hydrothermal alteration of wall rock which introduces clay minerals including kaolinite, smectite and illite. The process generally occurs at low temperatures and may occur in atmospheric conditions. Argillic alteration is representative of supergene environments where low temperature groundwater becomes acidic.

Hajigak Mine is the best known and largest iron oxide deposit in Afghanistan, located near the Hajigak Pass, with its area divided between Maidan Wardak and Bamyan provinces. It has the biggest untapped iron ore deposits of Asia.

Phyllic alteration is a hydrothermal alteration zone in a permeable rock that has been affected by circulation of hydrothermal fluids. It is commonly seen in copper porphyry ore deposits in calc-alkaline rocks. Phyllic alteration is characterised by the assemblage of quartz + sericite + pyrite, and occurs at high temperatures and moderately acidic conditions.

The Catoctin Formation is a geologic formation that expands through Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. It dates back to the Precambrian and is closely associated with the Harpers Formation, Weverton Formation, and the Loudoun Formation. The Catoctin Formation lies over a granitic basement rock and below the Chilhowee Group making it only exposed on the outer parts of the Blue Ridge. The Catoctin Formation contains metabasalt, metarhyolite, and porphyritic rocks, columnar jointing, low-dipping primary joints, amygdules, sedimentary dikes, and flow breccias. Evidence for past volcanic activity includes columnar basalts and greenstone dikes.