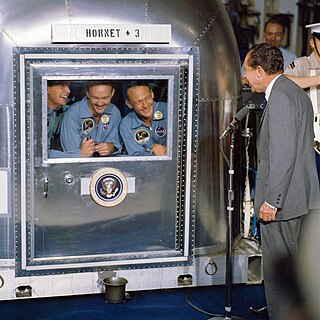

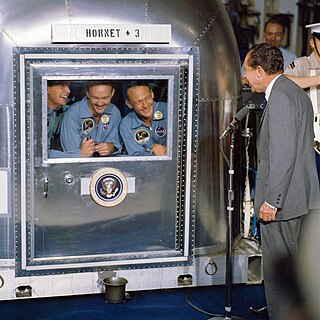

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have been exposed to a communicable disease, yet do not have a confirmed medical diagnosis. It is distinct from medical isolation, in which those confirmed to be infected with a communicable disease are isolated from the healthy population. Quarantine considerations are often one aspect of border control.

Aimable-Jean-Jacques Pélissier, 1st Duc de Malakoff, was a Marshal of France. He served in Algeria where he became widely known for his cruel conduct and extermination of entire tribes. He also served elsewhere, and as a general commanded the French forces in the Crimean War.

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin was a Russian statesman who served as the third prime minister and the interior minister of the Russian Empire from 1906 until his assassination in 1911. Known as the greatest reformer of Russian society and economy, his reforms caused unprecedented growth of the Russian state, which was halted by his assassination.

The November Uprising (1830–31), also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution, was an armed rebellion in the heartland of partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. The uprising began on 29 November 1830 in Warsaw when young Polish officers from the military academy of the Army of Congress Poland revolted, led by Lieutenant Piotr Wysocki. Large segments of the peoples of Lithuania, Belarus, and Right-bank Ukraine soon joined the uprising. Although the insurgents achieved local successes, a numerically superior Imperial Russian Army under Ivan Paskevich eventually crushed the uprising. The Russian Emperor Nicholas I issued the Organic Statute in 1832, according to which henceforth Russian-occupied Poland would lose its autonomy and become an integral part of the Russian Empire. Warsaw became little more than a military garrison, and its university closed.

Henry Tifft Gage was an American lawyer, politician and diplomat. A Republican, Gage was elected to a single term as the 20th governor of California from 1899 to 1903. Gage was also the U.S. Minister to Portugal for several months in 1910.

A cordon sanitaire is the restriction of movement of people into or out of a defined geographic area, such as a community, region, or country. The term originally denoted a barrier used to stop the spread of infectious diseases. The term is also often used metaphorically, in English, to refer to attempts to prevent the spread of an ideology deemed unwanted or dangerous, such as the containment policy adopted by George F. Kennan against the Soviet Union.

Cholera riots are civil disturbances associated with an outbreak or epidemic of cholera.

Black Sea Cossack Host, also known as Chernomoriya, was a Cossack host of the Russian Empire created in 1787 in southern Ukraine from former Zaporozhian Cossacks. In the 1790s, the host was re-settled to the Kuban River. It comprised the Caucasus Fortified Defence Line from the mouth of the Kuban River to the mouth of the Bolshaya Laba River.

The Great Plague of Marseille, also known as the Plague of Provence, was the last major outbreak of bubonic plague in Western Europe. Arriving in Marseille, France, in 1720, the disease killed over 100,000 people: 50,000 in the city during the next two years and another 50,000 to the north in surrounding provinces and towns.

The fifth cholera pandemic (1881–1896) was the fifth major international outbreak of cholera in the 19th century. It spread throughout Asia and Africa, and reached parts of France, Germany, Russia, and South America. It claimed 200,000 lives in Russia between 1893 and 1894; and 90,000 in Japan between 1887 and 1889. The 1892 outbreak in Hamburg, Germany was the biggest European outbreak; about 8,600 people died in that city. Although many residents held the city government responsible for the virulence of the epidemic, it continued with practices largely unchanged. This was the last serious European cholera outbreak of the century.

General Nicholas Nikolaievich Annenkov was an influential Russian General of the Infantry, Governor-General of Kiev and Bessarabia, and member of the State Privy Council. He was the brother of prominent Russian poet, Varvara Annenkova.

Ivan Antonovich Dumbadze was a Major-General of H. I. M. Retinue of Nicholas II, Supreme Head of Yalta, one of the activists of the Union of Russian People, notorious for his antisemitic and extravagant escapades.

Colonel John Vaughan (1778–1830) was a senior British officer in the service of the Honourable East India Company’s Army. Through his military career he saw active service on the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War, Second Anglo-Maratha War and Third Anglo-Maratha War.

During the Great Northern War (1700–1721), many towns and areas around the Baltic Sea and East-Central Europe had a severe outbreak of the plague with a peak from 1708 to 1712. This epidemic was probably part of a pandemic affecting an area from Central Asia to the Mediterranean. Most probably via Constantinople, it spread to Pińczów in southern Poland, where it was first recorded in a Swedish military hospital in 1702. The plague then followed trade, travel and army routes, reached the Baltic coast at Prussia in 1709, affected areas all around the Baltic Sea by 1711 and reached Hamburg by 1712. Therefore, the course of the war and the course of the plague mutually affected each other: while soldiers and refugees were often agents of the plague, the death toll in the military as well as the depopulation of towns and rural areas sometimes severely impacted the ability to resist enemy forces or to supply troops.

The Battle of Biržai was a series of skirmishes during the January Uprising. They took place on May 7–9, 1863, in the area of Lithuanian town of Biržai, at the time part of the Russian Empire's Kaunas Governorate. Lithuanian rebels commanded by Zygmunt Sierakowski, clashed here with the Imperial Russian Army.

The Governor of Sevastopol is head of the executive branch of the political system in the city of Sevastopol. The governor's office administers all city services, public property, police and fire protection, most public agencies, and enforces all city and state laws within Sevastopol.

The 29th Chernigov Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment of the Russian Imperial Army.

The Lazzarettos of Dubrovnik is a group of interconnected buildings located 300 meters away from the walls of Dubrovnik that were once used as a quarantine station for the Republic of Ragusa.

The 1813–1814 Malta plague epidemic was the last major outbreak of plague on the islands of Malta and Gozo. It occurred between March 1813 and January 1814 on Malta and between February and May 1814 on Gozo, and the epidemic was officially declared to be over in September 1814. It resulted in approximately 4500 deaths, which was about 5% of the islands' population.

Fedor Sergeyevich Panyutin was a Russian general, Warsaw military governor, and member of the State Council.