Kwee Tek Hoay was a Chinese Indonesian Malay-language writer of novels and drama, and a journalist.

Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari is an 1884 Malay-language syair (poem) by Lie Kim Hok. Adapted indirectly from the Sjair Abdoel Moeloek, it tells of a woman who passes as a man to free her husband from the Sultan of Hindustan, who had captured him in an assault on their kingdom.

Lie Kim Hok was a peranakan Chinese teacher, writer, and social worker active in the Dutch East Indies and styled the "father of Chinese Malay literature". Born in Buitenzorg, West Java, Lie received his formal education in missionary schools and by the 1870s was fluent in Sundanese, vernacular Malay, and Dutch, though he was unable to understand Chinese. In the mid-1870s he married and began working as the editor of two periodicals published by his teacher and mentor D. J. van der Linden. Lie left the position in 1880. His wife died the following year. Lie published his first books, including the critically acclaimed syair (poem) Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari and grammar book Malajoe Batawi, in 1884. When van der Linden died the following year, Lie purchased the printing press and opened his own company.

Tio Ie Soei was a peranakan Chinese writer and journalist active in the Dutch East Indies and Indonesia. Born in the capital at Batavia, Tio entered journalism while still a teenager. By 1911 he had begun writing fiction, publishing Sie Po Giok – his first novel – that year. Over the next 50 years Tio wrote extensively in several newspapers and magazines, serving as an editor for some. He also wrote several novels and biographies, including ones on Tan Sie Tat and Lie Kim Hok.

Phoa Keng Hek Sia was a Chinese Indonesian Landheer (landlord), social activist and founding president of Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan, an influential Confucian educational and social organisation meant to better the position of ethnic Chinese in the Dutch East Indies. He was also one of the founders of Institut Teknologi Bandung.

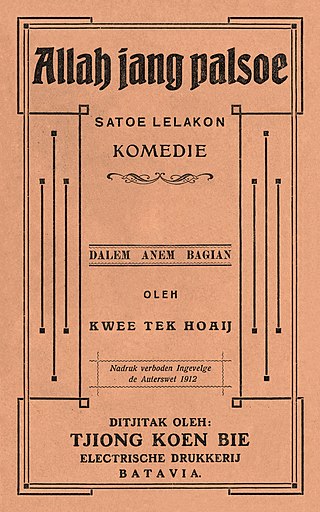

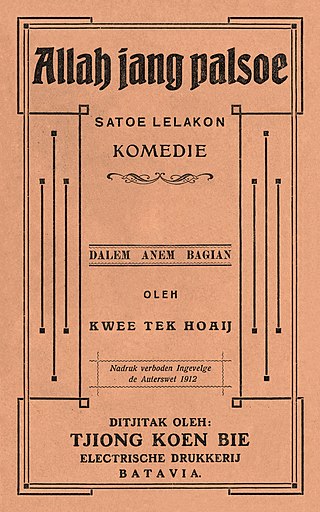

Allah jang Palsoe is a 1919 stage drama from the Dutch East Indies that was written by the ethnic Chinese author Kwee Tek Hoay based on E. Phillips Oppenheim's short story "The False Gods". Over six acts, the Malay-language play follows two brothers, one a devout son who holds firmly to his morals and personal honour, while the other worships money and prioritises personal gain. Over more than a decade, the two learn that money is not the path to happiness.

Thio Tjin Boen was a Chinese-Indonesian writer of Malay-language fiction and a journalist.

Tjerita "Oeij-se": Jaitoe Satoe Tjerita jang Amat Endah dan Loetjoe, jang Betoel Soedah Kedjadian di Djawa Tengah is a 1903 Malay-language novel by the ethnic Chinese writer Thio Tjin Boen. It details the rise of a Chinese businessman who becomes rich after finding a kite made of paper money in a village, who then uses dishonesty to advance his personal wealth before disowning his daughter after she converts to Islam and marries a Javanese man.

Tjhit Liap Seng, also known as Bintang Toedjoeh in Malay, is an 1886 novel by Lie Kim Hok. It is considered the first Chinese Malay novel.

Tan Boen Soan was an ethnic Chinese Malay-language writer and journalist from Sukabumi, Java. He was the author of works such as Koetoekannja Boenga Srigading (1933), Bergerak (1935), Digdaja (1935) and Tjoban (1936). He later wrote for the Sunday Courier of Jakarta.

Lauw Giok Lan was a Chinese Indonesian journalist and writer. He was one of the founders of the newspaper Sin Po.

Letnan Cina Oey Thai Lo was a notable Chinese-Indonesian tycoon who acted as a pachter for tobacco in the early 19th century.

The Ngo Ho TjiangKongsi, sometimes spelled Ngo Houw Tjiang, was a powerful consortium that dominated the opium pacht or tax farm of the Residency of Batavia, Dutch East Indies in the early to mid-nineteenth century. The pacht was an outsourced tax operation, collecting customs, excise and indirect duties on behalf of the Dutch colonial government.

Tjoe Boe San was a Chinese nationalist, translator and newspaper editor in the Dutch East Indies, most notably editor and director of the influential Indonesian Chinese newspaper Sin Po until his death in 1925. Along with Kwee Kek Beng, he was a key member of the "Sin Po Group" which was a political faction of the Indonesian Chinese which believed that they should stay out of Dutch colonial politics and remain focused on China.

Yap Goan Ho was a Chinese Indonesian translator, businessman, bookseller, and publisher based in Batavia, Dutch East Indies. In the 1880s and 1890s, he was one of the first Chinese Indonesians to own a printing press and the first to publish Chinese language novels in Malay language translations.

Tan Tiang Po, Luitenant der Chinezen, also spelled Tan Tjeng Po, was a colonial Chinese-Indonesian bureaucrat, landowner, philanthropist and the penultimate Landheer (landlord) of the domain of Batoe-Tjepper in the Dutch East Indies.

Oey Liauw Kong, Kapitein der Chinezen (1799–1865) was a Chinese-Indonesian high official, Landheer (landlord) and head of the Oey family of Kemiri, part of the 'Tjabang Atas' or Peranakan gentry. He was also the owner of the 18th-century Baroque mansion and Jakarta landmark, Toko Merah.

Phoa Tjoen Hoay, who sometimes published as T. H. Phoa Jr., was a Chinese Indonesian, Malay language journalist, translator, and newspaper editor active in the Dutch East Indies in the early twentieth century. He translated a number of Chinese and European works into Malay, including seven volumes of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle.

Lie Sim Djwe, who also published under the name Lie Sien Djioe, was a Chinese Indonesian writer, journalist and translator active in the Dutch East Indies and Indonesia from the 1910s until the 1950s. His major contribution was the translation of Chinese-language novels into Malay.