Related Research Articles

Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari is an 1884 Malay-language syair (poem) by Lie Kim Hok. Adapted indirectly from the Sjair Abdoel Moeloek, it tells of a woman who passes as a man to free her husband from the Sultan of Hindustan, who had captured him in an assault on their kingdom.

Lie Kim Hok was a peranakan Chinese teacher, writer, and social worker active in the Dutch East Indies and styled the "father of Chinese Malay literature". Born in Buitenzorg, West Java, Lie received his formal education in missionary schools and by the 1870s was fluent in Sundanese, vernacular Malay, and Dutch, though he was unable to understand Chinese. In the mid-1870s he married and began working as the editor of two periodicals published by his teacher and mentor D. J. van der Linden. Lie left the position in 1880. His wife died the following year. Lie published his first books, including the critically acclaimed syair (poem) Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari and grammar book Malajoe Batawi, in 1884. When van der Linden died the following year, Lie purchased the printing press and opened his own company.

Boenga Roos dari Tjikembang is a 1927 vernacular Malay-language novel written by Kwee Tek Hoay. The seventeen-chapter book follows a plantation manager, Aij Tjeng, who must leave his beloved njai (concubine) Marsiti so that he can be married. Eighteen years later, after Aij Tjeng's daughter Lily dies, her fiancé Bian Koen discovers that Marsiti had a daughter with Aij Tjeng, Roosminah, who greatly resembles Lily. In the end Bian Koen and Roosminah are married.

Tio Ie Soei was a peranakan Chinese writer and journalist active in the Dutch East Indies and Indonesia. Born in the capital at Batavia, Tio entered journalism while still a teenager. By 1911 he had begun writing fiction, publishing Sie Po Giok – his first novel – that year. Over the next 50 years Tio wrote extensively in several newspapers and magazines, serving as an editor for some. He also wrote several novels and biographies, including ones on Tan Sie Tat and Lie Kim Hok.

Tjerita Sie Po Giok, atawa Peroentoengannja Satoe Anak Piatoe is a 1911 children's novel from the Dutch East Indies written by Tio Ie Soei in vernacular Malay. It tells the story of Sie Po Giok, a young orphan who faces several challenges while living with his uncle in Batavia. The story, which has been called the only work of children's literature produced by Chinese Malay writers, has been read as promoting traditional gender roles and questioning Chinese identity.

Tjěrita Si Tjonat, Sato Kěpala Pěnjamoen di Djaman Dahoeloe Kala is a 1900 novel written by the journalist F. D. J. Pangemanann. One of numerous bandit stories from the contemporary Indies, it follows the rise and fall of Tjonat, from his first murder at the age of thirteen until his execution some twenty-five years later. The novel's style, according to Malaysian scholar Abdul Wahab Ali, is indicative of a transitional period between orality and written literature. Tjerita Si Tjonat has been adapted to the stage multiple times, and in 1929 a film version was made.

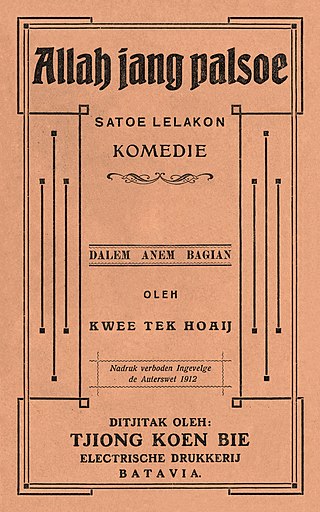

Allah jang Palsoe is a 1919 stage drama from the Dutch East Indies that was written by the ethnic Chinese author Kwee Tek Hoay based on E. Phillips Oppenheim's short story "The False Gods". Over six acts, the Malay-language play follows two brothers, one a devout son who holds firmly to his morals and personal honour, while the other worships money and prioritises personal gain. Over more than a decade, the two learn that money is not the path to happiness.

Thio Tjin Boen was a Chinese-Indonesian writer of Malay-language fiction and a journalist.

Tjhit Liap Seng, also known as Bintang Toedjoeh in Malay, is an 1886 novel by Lie Kim Hok. It is considered the first Chinese Malay novel.

Drama dari Krakatau is a 1929 vernacular Malay novel written by Kwee Tek Hoay. Inspired by Edward Bulwer-Lytton's 1834 novel The Last Days of Pompeii and the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, the sixteen-chapter book centres on two families in 1920s Batam that are unknowingly tied together by siblings who were separated in 1883. The brother becomes a political figure, while the sister marries a Baduy priest-king. Ultimately, these families are reunited by the wedding of their children, after which the priest sacrifices himself to calm a stirring Krakatoa.

Tan Boen Soan was an ethnic Chinese Malay-language writer and journalist from Sukabumi, Java. He was the author of works such as Koetoekannja Boenga Srigading (1933), Bergerak (1935), Digdaja (1935) and Tjoban (1936). He later wrote for the Sunday Courier of Jakarta.

Lauw Giok Lan was a Chinese Indonesian journalist and writer. He was one of the founders of the newspaper Sin Po.

Tan Eng Goan, 1st Majoor der Chinezen was a high-ranking bureaucrat who served as the first Majoor der Chinezen of Batavia, capital of colonial Indonesia. This was the highest-ranking Chinese position in the civil administration of the Dutch East Indies.

Oey Tamba Sia, also spelt Oeij Tambah Sia, or often mistakenly Oey Tambahsia, was a rich, Chinese-Indonesian playboy hanged by the Dutch colonial government due to his involvement in a number of murder cases in Batavia, now Jakarta, capital of colonial Indonesia. His life has become part of Jakarta folklore, and inspired numerous literary works.

Letnan Cina Oey Thai Lo was a notable Chinese-Indonesian tycoon who acted as a pachter for tobacco in the early 19th century.

Lim Soe Keng Sia, also known as Liem Soe King Sia, Soe King Sia or Lim Soukeng Sia, was a Pachter, or revenue farmer, in Batavia, capital of the Dutch East Indies, best known for his rivalry with the notorious Betawi playboy Oey Tamba Sia. He acted as administrator of the 'Ngo Ho Tjiang' Kongsi, the most influential consortium of opium monopolists in early to mid-19th century Batavia.

Oey Giok Koen, Kapitein der Chinezen was a Chinese-Indonesian public figure, bureaucrat and Landheer, best known for his role as Kapitein der Chinezen of Tangerang and Meester Cornelis, and as one of the richest landowners in the Dutch East Indies. As Kapitein, he headed the local Chinese civil administration in Tangerang and Meester Cornelis as part of the Dutch colonial system of 'indirect rule'. In 1893, he bought the particuliere landen or private domains of Tigaraksa and Pondok Kosambi.

Tjerita Roman was a monthly Peranakan Chinese, Malay-language literary magazine published in the Dutch East Indies from 1929 to 1942. It was one of the most successful literary publications in the Indies, publishing hundreds of novels, plays, and short stories during its run. Among its authors were many of the notables of the Chinese Indonesian literary world including Njoo Cheong Seng, Pouw Kioe An, Tan Boen Soan, and Liem Khing Hoo.

References

- 1 2 Phoa, Kian Sioe (1956). Sedjarahnja Souw Beng Kong: (tangan-kanannja G.G. Jan Pieterszoon Coen), Phoa Beng Gan (achli pengairan dalam tahun 1648), Oey Tamba Sia (hartawan mati ditiang penggantungan) (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Reporter.

- ↑ JCG, Thio Tjin Boen.

- 1 2 Sumardjo 2004, p. 170.

- ↑ Sumardjo 2004, p. 169.

- ↑ Suryadinata 1993, p. 103.

- ↑ Nio 1962, p. 44.

- 1 2 Sumardjo 2004, pp. 167–168.

- ↑ Suryadinata 1993, p. 104.

- 1 2 Sim 2010, p. 240.

- ↑ Sim 2010, p. 241.

- ↑ Sim 2010, p. 242.

- ↑ Sumardjo 2004, p. 164.

- ↑ Thio 2000, p. 175.

- ↑ Sumardjo 2004, p. 165.