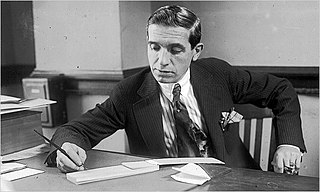

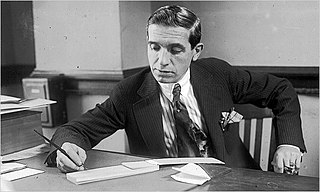

Charles Ponzi was an Italian charlatan and con artist who operated in the United States and Canada. His aliases included Charles Ponci, Carlo, and Charles P. Bianchi.

A Ponzi scheme is a form of fraud that lures investors and pays profits to earlier investors with funds from more recent investors. Named after Italian businessman Charles Ponzi, this type of scheme misleads investors by either falsely suggesting that profits are derived from legitimate business activities, or by exaggerating the extent and profitability of the legitimate business activities, leveraging new investments to fabricate or supplement these profits. A Ponzi scheme can maintain the illusion of a sustainable business as long as investors continue to contribute new funds, and as long as most of the investors do not demand full repayment or lose faith in the non-existent assets they are purported to own.

Edwin Atkins Grozier was an American journalist, publisher and author, who owned The Boston Post from 1891 until his death. He authored the book, "The Wreck of the 'Somerset,'" first published in the New York World, May 1886.

Melvin Morse Swig was an American real estate developer and philanthropist. He was also the owner of the National Hockey League's California Golden Seals and Cleveland Barons.

Hyman Philip Minsky was an American economist, a professor of economics at Washington University in St. Louis, and a distinguished scholar at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. His research attempted to provide an understanding and explanation of the characteristics of financial crises, which he attributed to swings in a potentially fragile financial system. Minsky is sometimes described as a post-Keynesian economist because, in the Keynesian tradition, he supported some government intervention in financial markets, opposed some of the financial deregulation of the 1980s, stressed the importance of the Federal Reserve as a lender of last resort and argued against the over-accumulation of private debt in the financial markets.

School Street is a short but significant street in the center of Boston, Massachusetts. It is so named for being the site of the first public school in the United States. The school operated at various addresses on the street from 1704 to 1844.

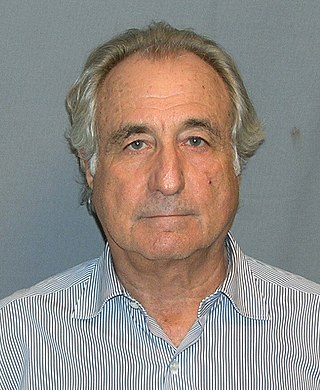

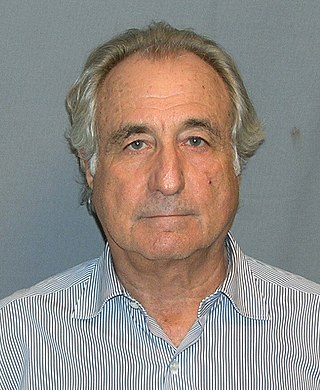

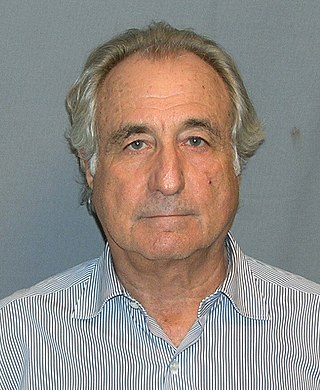

The Madoff investment scandal was a major case of stock and securities fraud discovered in late 2008. In December of that year, Bernie Madoff, the former Nasdaq chairman and founder of the Wall Street firm Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC, admitted that the wealth management arm of his business was an elaborate multi-billion-dollar Ponzi scheme.

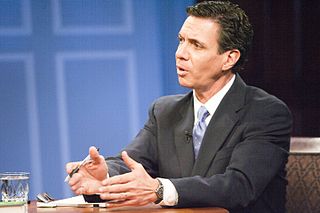

Mitchell S. Zuckoff is an American professor of communications at Boston University. His books include Lost in Shangri-La and 13 Hours (2014).

Participants in the Madoff investment scandal included employees of Bernard Madoff's investment firm with specific knowledge of the Ponzi scheme, a three-person accounting firm that assembled his reports, and a network of feeder funds that invested their clients' money with Madoff while collecting significant fees. Madoff avoided most direct financial scrutiny by accepting investments only through these feeder funds, while obtaining false auditing statements for his firm. The liquidation trustee of Madoff's firm has implicated managers of the feeder funds for ignoring signs of Madoff's deception.

Riad Toufic Salameh is a Lebanese economist. He previously served as governor of Lebanon's central bank, Banque du Liban, from April 1993 until July 2023. He was appointed Governor by decree, approved by the Council of Ministers for a renewable term of six years. He was reappointed for four consecutive terms; in 1999, 2005, 2011 and 2017. Riad Salameh left his position on 31 July 2023 upon the end of his term, and due to the Lebanese parliament’s failure in electing a new president and forming a new government capable of appointing a successor he was succeeded by his first deputy Wassim Mansouri in an acting capacity

Fred Jefferson Burrell was a Massachusetts businessman and politician who served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives and as Treasurer and Receiver-General of Massachusetts from January 21, 1920 – September 3, 1920.

The Provident Institution for Savings (est.1816) in Boston, Massachusetts, was the first chartered savings bank in the United States. James Savage and others founded the bank on the belief that "savings banks would enable the less fortunate classes of society to better themselves in a manner which would avoid the dangers of moral corruption traditionally associated with outright charitable institutions."

Charlestown State Prison was a correctional facility in Charlestown, Boston, Massachusetts operated by the Massachusetts Department of Correction. The facility was built at Lynde's Point, now at the intersection of Austin Street and New Rutherford Avenue, and in proximity to the Boston and Maine Railroad tracks that intersected with the Eastern Freight Railroad tracks. Bunker Hill Community College occupies the site that the prison once occupied.

Richard Grozier (1887–1946) was the owner, publisher and editor of The Boston Post from 1924 until his death. He inherited the paper from his father, Edwin Grozier. While he was acting publisher in 1920, The Boston Post received one of the first Pulitzer prizes for exposing Charles Ponzi as a fraud.

The Hanover Trust Company was a private American bank of the 1920s. Its offices were located in Boston, Massachusetts.

Benjamin Harrison Swig was a real estate developer and a philanthropist active in Jewish and non-Jewish communities.

Sarah Emily Howe was an American fraudster who operated several Ponzi schemes—although her schemes predated namesake Charles Ponzi by several decades—in the 1870s and 1880s. Her most well-known deception was the Ladies' Deposit Company of Boston. Howe was arrested in 1880 and imprisoned for three years for fraud. Upon her release, she repeated similar frauds until she was arrested again in 1888.

The 1936 Massachusetts gubernatorial election was held on November 3, 1936.

William Henry McMasters was an American journalist and publicist who exposed Charles Ponzi as a fraudster.