Related Research Articles

A tornado is a violently rotating column of air that is in contact with both the surface of the Earth and a cumulonimbus cloud or, in rare cases, the base of a cumulus cloud. It is often referred to as a twister, whirlwind or cyclone, although the word cyclone is used in meteorology to name a weather system with a low-pressure area in the center around which, from an observer looking down toward the surface of the Earth, winds blow counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern. Tornadoes come in many shapes and sizes, and they are often visible in the form of a condensation funnel originating from the base of a cumulonimbus cloud, with a cloud of rotating debris and dust beneath it. Most tornadoes have wind speeds less than 180 kilometers per hour, are about 80 meters across, and travel several kilometers before dissipating. The most extreme tornadoes can attain wind speeds of more than 480 kilometers per hour (300 mph), are more than 3 kilometers (2 mi) in diameter, and stay on the ground for more than 100 km (62 mi).

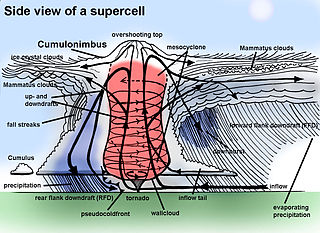

A supercell is a thunderstorm characterized by the presence of a mesocyclone; a deep, persistently rotating updraft. Due to this, these storms are sometimes referred to as rotating thunderstorms. Of the four classifications of thunderstorms, supercells are the overall least common and have the potential to be the most severe. Supercells are often isolated from other thunderstorms, and can dominate the local weather up to 32 kilometres (20 mi) away. They tend to last 2–4 hours.

A mesocyclone is a meso-gamma mesoscale region of rotation (vortex), typically around 2 to 6 mi in diameter, most often noticed on radar within thunderstorms. In the northern hemisphere it is usually located in the right rear flank of a supercell, or often on the eastern, or leading, flank of a high-precipitation variety of supercell. The area overlaid by a mesocyclone’s circulation may be several miles (km) wide, but substantially larger than any tornado that may develop within it, and it is within mesocyclones that intense tornadoes form.

On March 18, 1925, one of the deadliest tornado outbreaks in recorded history generated at least twelve significant tornadoes and spanned a large portion of the midwestern and southern United States. In all, at least 751 people were killed and more than 2,298 were injured, making the outbreak the deadliest tornado outbreak, March 18 the deadliest tornado day, and 1925 the deadliest tornado year in U.S. history. The outbreak generated several destructive tornadoes in Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana on the same day, as well as significant tornadoes in Alabama and Kansas. In addition to confirmed tornadoes, there were undoubtedly others with lesser impacts, the occurrences of which have been lost to history.

The 1999 Oklahoma tornado outbreak was a significant tornado outbreak that affected much of the Central and parts of the Eastern United States, with the highest record-breaking wind speeds of 301 ± 20 mph (484 ± 32 km/h). During this week-long event, 154 tornadoes touched down. More than half of them were on May 3 and 4 when activity reached its peak over Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Texas, and Arkansas.

A wall cloud is a large, localized, persistent, and often abrupt lowering of cloud that develops beneath the surrounding base of a cumulonimbus cloud and from which tornadoes sometimes form. It is typically beneath the rain-free base (RFB) portion of a thunderstorm, and indicates the area of the strongest updraft within a storm. Rotating wall clouds are an indication of a mesocyclone in a thunderstorm; most strong tornadoes form from these. Many wall clouds do rotate; however, some do not.

Tornado myths are incorrect beliefs about tornadoes, which can be attributed to many factors, including stories and news reports told by people unfamiliar with tornadoes, sensationalism by news media, and the presentation of incorrect information in popular entertainment. Common myths cover various aspects of the tornado, and include ideas about tornado safety, the minimization of tornado damage, and false assumptions about the size, shape, power, and path of the tornado itself.

A funnel cloud is a funnel-shaped cloud of condensed water droplets, associated with a rotating column of wind and extending from the base of a cloud but not reaching the ground or a water surface. A funnel cloud is usually visible as a cone-shaped or needle like protuberance from the main cloud base. Funnel clouds form most frequently in association with supercell thunderstorms, and are often, but not always, a visual precursor to tornadoes. Funnel clouds are visual phenomena, these are not the vortex of wind itself.

A multiple-vortex tornado is a tornado that contains several vortices revolving around, inside of, and as part of the main vortex. The only times multiple vortices may be visible are when the tornado is first forming or when condensation and debris are balanced such that subvortices are apparent without being obscured. They can add over 100 mph to the ground-relative wind in a tornado circulation and are responsible for most cases where narrow arcs of extreme destruction lie right next to weak damage within tornado paths.

An outflow boundary, also known as a gust front, is a storm-scale or mesoscale boundary separating thunderstorm-cooled air (outflow) from the surrounding air; similar in effect to a cold front, with passage marked by a wind shift and usually a drop in temperature and a related pressure jump. Outflow boundaries can persist for 24 hours or more after the thunderstorms that generated them dissipate, and can travel hundreds of kilometers from their area of origin. New thunderstorms often develop along outflow boundaries, especially near the point of intersection with another boundary. Outflow boundaries can be seen either as fine lines on weather radar imagery or else as arcs of low clouds on weather satellite imagery. From the ground, outflow boundaries can be co-located with the appearance of roll clouds and shelf clouds.

A fire whirl or fire devil is a whirlwind induced by a fire and often composed of flame or ash. These start with a whirl of wind, often made visible by smoke, and may occur when intense rising heat and turbulent wind conditions combine to form whirling eddies of air. These eddies can contract a tornado-like vortex that sucks in debris and combustible gases.

Landspout is a term created by atmospheric scientist Howard B. Bluestein in 1985 for a tornado not associated with a mesocyclone. The Glossary of Meteorology defines a landspout as

Tornadogenesis is the process by which a tornado forms. There are many types of tornadoes and these vary in methods of formation. Despite ongoing scientific study and high-profile research projects such as VORTEX, tornadogenesis is a volatile process and the intricacies of many of the mechanisms of tornado formation are still poorly understood.

The rear flank downdraft (RFD) is a region of dry air wrapping around the back of a mesocyclone in a supercell thunderstorm. These areas of descending air are thought to be essential in the production of many supercellular tornadoes. Large hail within the rear flank downdraft often shows up brightly as a hook on weather radar images, producing the characteristic hook echo, which often indicates the presence of a tornado.

A tornado family is a series of tornadoes spawned by the same supercell thunderstorm. These families form a line of successive or parallel tornado paths and can cover a short span or a vast distance. Tornado families are sometimes mistaken as a single continuous tornado, especially prior to the 1970s. Sometimes the tornado tracks can overlap and expert analysis is necessary to determine whether or not damage was created by a family or a single tornado. In some cases, such as the Hesston-Goessel, Kansas tornadoes of March 1990, different tornadoes of a tornado family merge, making discerning whether an event was continuous or not more difficult.

Convective storm detection is the meteorological observation, and short-term prediction, of deep moist convection (DMC). DMC describes atmospheric conditions producing single or clusters of large vertical extension clouds ranging from cumulus congestus to cumulonimbus, the latter producing thunderstorms associated with lightning and thunder. Those two types of clouds can produce severe weather at the surface and aloft.

The March 1990 Central United States tornado outbreak affected portions of the United States Great Plains and Midwest regions from Iowa to Texas from March 11 to March 13, 1990. The outbreak produced at least 64 tornadoes across the region, including four violent tornadoes; two tornadoes, which touched down north and west of Wichita, Kansas, were both rated F5, including the tornado that struck Hesston. In Nebraska, several strong tornadoes touched down across the southern and central portion of the state, including an F4 tornado that traveled for 131 miles (211 km) making it the longest tracked tornado in the outbreak. Two people were killed in the outbreak, one each by the two F5 tornadoes in Kansas.

A mesovortex is a small-scale rotational feature found in a convective storm, such as a quasi-linear convective system, a supercell, or the eyewall of a tropical cyclone. Mesovortices range in diameter from tens of miles to a mile or less and can be immensely intense.

The following is a glossary of tornado terms. It includes scientific as well as selected informal terminology.

This glossary of meteorology is a list of terms and concepts relevant to meteorology and atmospheric science, their sub-disciplines, and related fields.

References

- ↑ Charles A. Doswell III (1 October 2001). "What is a tornado?" . Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ↑ Roger Edwards (2014). "Skipping tornado". The Online Tornado FAQ. Storm Prediction Center . Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Charles A. Doswell III (1 October 2001). "What is a tornado? (footnotes)" . Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ↑ Doswell, Charles A. III; D. W. Burgess (1988). "On Some Issues of United States Tornado Climatology". Mon. Wea. Rev. 116 (2): 495–501. Bibcode:1988MWRv..116..495D. doi: 10.1175/1520-0493(1988)116<0495:OSIOUS>2.0.CO;2 .