Polarization is a property of transverse waves which specifies the geometrical orientation of the oscillations. In a transverse wave, the direction of the oscillation is perpendicular to the direction of motion of the wave. A simple example of a polarized transverse wave is vibrations traveling along a taut string (see image); for example, in a musical instrument like a guitar string. Depending on how the string is plucked, the vibrations can be in a vertical direction, horizontal direction, or at any angle perpendicular to the string. In contrast, in longitudinal waves, such as sound waves in a liquid or gas, the displacement of the particles in the oscillation is always in the direction of propagation, so these waves do not exhibit polarization. Transverse waves that exhibit polarization include electromagnetic waves such as light and radio waves, gravitational waves, and transverse sound waves in solids.

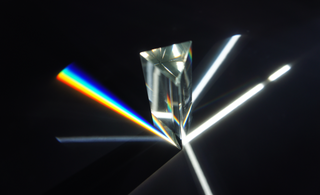

An optical prism is a transparent optical element with flat, polished surfaces that are designed to refract light. At least one surface must be angled — elements with two parallel surfaces are not prisms. The most familiar type of optical prism is the triangular prism, which has a triangular base and rectangular sides. Not all optical prisms are geometric prisms, and not all geometric prisms would count as an optical prism. Prisms can be made from any material that is transparent to the wavelengths for which they are designed. Typical materials include glass, acrylic and fluorite.

In social psychology, group polarization refers to the tendency for a group to make decisions that are more extreme than the initial inclination of its members. These more extreme decisions are towards greater risk if individuals' initial tendencies are to be risky and towards greater caution if individuals' initial tendencies are to be cautious. The phenomenon also holds that a group's attitude toward a situation may change in the sense that the individuals' initial attitudes have strengthened and intensified after group discussion, a phenomenon known as attitude polarization.

The hostile media effect, originally deemed the hostile media phenomenon and sometimes called hostile media perception, is a perceptual theory of mass communication that refers to the tendency for individuals with a strong preexisting attitude on an issue to perceive media coverage as biased against their side and in favor of their antagonists' point of view. Partisans from opposite sides of an issue will tend to find the same coverage to be biased against them. The phenomenon was first proposed and studied experimentally by Robert Vallone, Lee Ross and Mark Lepper.

Political polarization is the divergence of political attitudes away from the center, towards ideological extremes.

Political socialization is the process by which individuals internalize and develop their political values, ideas, attitudes, and perceptions via the agents of socialization. Agents such as family, education, media, and peers influence the most in establishing varying political lenses that frame one's perception of political values, ideas, and attitudes. These perceptions, in turn, shape and define individuals' definitions of who they are and how they should behave in the political and economic institutions in which they live. This learning process shapes perceptions that influence which norms, behaviors, values, opinions, morals, and priorities will ultimately shape their political ideology: it is a "study of the developmental processes by which people of all ages and adolescents acquire political cognition, attitudes, and behaviors." These agents expose individuals Through varying degrees of influence, inducing them into the political culture and their orientations towards political objects. Throughout a lifetime, these experiences influence your political identity and shape your political outlook.

Social exclusion or social marginalisation is the social disadvantage and relegation to the fringe of society. It is a term that has been used widely in Europe and was first used in France in the late 20th century. It is used across disciplines including education, sociology, psychology, politics and economics.

Erik Achille Marie Swyngedouw is professor of geography at the University of Manchester in the School of Environment, Education and Development and a member of the Manchester Urban Institute.

Frank Moulaert is Professor of Spatial Planning at the Department of Architecture, Urban Design and Regional Planning at Catholic University of Leuven. He is Director of the Urban and Regional Planning Research Group and chairs the Leuven Space and Society Research Centre at the University. He is also a Visiting Professor at the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, Newcastle University.

The Globalized City: Economic Restructing and Social Polarization in European Cities is a collection of discussions and case studies of large-scale urban development projects in nine European cities. It analyzes the relation between these projects and trends such as social exclusion, the emergence of new urban elites, and the consolidation of less democratic forms of urban governance.

Social access is a concept of the delivery of public services, facilities and amenities to intended user groups. Limited access may be due to their high cost, the lack of appropriate infrastructure or due to prejudices within the society that restrict use. Urban policy makers plan for universal access to potable water, sewerage disposal, solid waste disposal, medical aid and education. Policies may assume that the private sector delivers some or a part of these requirements. The actual "reach" of these systems is usually far less than required. This is particularly a concern in emerging, rapidly urbanizing societies.

Edward Soja uses the term fractal city to describe the "metropolarities" and the restructured social mosaic of today's urban landscape or "postmetropolis". In his book, Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions, he discusses how the contemporary American city has become far more complex than the familiar upper class vs. middle class or black vs. white models of society. It has become a fractal city of intensified inequalities and social polarization. The term "fractal" gives it the idea of having a fractured social geometry. This is a patterning of metropolarities, or an intensification of socio-economic inequalities, some of which Soja tries to pinpoint and discuss.

In news media and social media, an echo chamber is an environment or ecosystem in which participants encounter beliefs that amplify or reinforce their preexisting beliefs by communication and repetition inside a closed system and insulated from rebuttal. An echo chamber circulates existing views without encountering opposing views, potentially resulting in confirmation bias. Echo chambers may increase social and political polarization and extremism. On social media, it is thought that echo chambers limit exposure to diverse perspectives, and favor and reinforce presupposed narratives and ideologies.

Economic restructuring is used to indicate changes in the constituent parts of an economy in a very general sense. In the western world, it is usually used to refer to the phenomenon of urban areas shifting from a manufacturing to a service sector economic base. It has profound implications for productive capacities and competitiveness of cities and regions. This transformation has affected demographics including income distribution, employment, and social hierarchy; institutional arrangements including the growth of the corporate complex, specialized producer services, capital mobility, informal economy, nonstandard work, and public outlays; as well as geographic spacing including the rise of world cities, spatial mismatch, and metropolitan growth differentials.

The Leopold Quarter is a quarter of Brussels, Belgium. Today, the term is sometimes confused with the European Quarter, as the area has come to be dominated by the institutions of the European Union (EU) and organisations dealing with them, although the two terms are not in fact the same, with the Leopold Quarter being a smaller more specific district of the municipalities of the City of Brussels, Etterbeek, Ixelles and Saint-Josse-ten-Noode.

Geographic information system (GIS) is a commonly used tool for environmental management, modelling and planning. As simply defined by Michael Goodchild, GIS is as "a computer system for handling geographic information in a digital form". In recent years it has played an integral role in participatory, collaborative and open data philosophies. Social and technological evolutions have elevated digital and environmental agendas to the forefront of public policy, the global media and the private sector.

Environmental, ecological or green gentrification is a process in which cleaning up pollution or providing green amenities increases local property values and attracts wealthier residents to a previously polluted or disenfranchised neighbourhood. Green amenities include green spaces, parks, green roofs, gardens and green and energy efficient building materials. These initiatives can heal many environmental ills from industrialization and beautify urban landscapes. Additionally, greening is imperative for reaching a sustainable future. However, if accompanied by gentrification, these initiatives can have an ambiguous social impact. For example, if the low income households are displaced or forced to pay higher housing costs. First coined by Sieg et al. (2004), environmental gentrification is a relatively new concept, although it can be considered as a new hybrid of the older and wider topics of gentrification and environmental justice. Social implications of greening projects specifically with regards to housing affordability and displacement of vulnerable citizens. Greening in cities can be both healthy and just.

Political polarization is a prominent component of politics in the United States. Scholars distinguish between ideological polarization and affective polarization, both of which are apparent in the United States. In the last few decades, the U.S. has experienced a greater surge in ideological polarization and affective polarization than comparable democracies.

Political polarization is the bimodal distribution, meaning that two obvious peaks of opinion in the political sense. It can be observed through people's choices, sociopolitical approaches, and even where they live. In the last years, political polarization has caused many political results in the governments and the law-making organs. However it may not be classified as a "negative" aspect, and it can be used by politicians to examine the social and economic parts to develop in a country. Citizens would be more prone to do skeptical analysis on the subjects, and gain more meaning in their lives. Mexico, Turkey, India, South Africa, Brazil and Venezuela are amongst the countries that have the highest polarization.

Audience fragmentation describes the extent to which audiences are distributed across media offerings. Traditional outlets, such as broadcast networks, have long feared that technological and regulatory changes would increase competition and erode their audiences. Social scientists have been concerned about the loss of a common cultural forum and rise of extremist media. Hence, many representations of fragmentation have focused on media outlets as the unit of analysis and reported the status of their audiences. But fragmentation can also be conceptualized at the level of individuals and audiences, revealing different features of the phenomenon. Webster and Ksiazek have argued there are three types of fragmentation: media-centric, user-centric, and audience-centric