Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio (incised) in the metal. In modern manufacturing, other chemicals may be used on other types of material. As a method of printmaking, it is, along with engraving, the most important technique for old master prints, and remains in wide use today. In a number of modern variants such as microfabrication etching and photochemical milling it is a crucial technique in much modern technology, including circuit boards.

Printmaking is the process of creating artworks by printing, normally on paper, but also on fabric, wood, metal, and other surfaces. "Traditional printmaking" normally covers only the process of creating prints using a hand processed technique, rather than a photographic reproduction of a visual artwork which would be printed using an electronic machine ; however, there is some cross-over between traditional and digital printmaking, including risograph. Except in the case of monotyping, all printmaking processes have the capacity to produce identical multiples of the same artwork, which is called a print. Each print produced is considered an "original" work of art, and is correctly referred to as an "impression", not a "copy". However, impressions can vary considerably, whether intentionally or not. Master printmakers are technicians who are capable of printing identical "impressions" by hand. Historically, many printed images were created as a preparatory study, such as a drawing. A print that copies another work of art, especially a painting, is known as a "reproductive print".

Engraving is the practice of incising a design onto a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an intaglio printing plate, of copper or another metal, for printing images on paper as prints or illustrations; these images are also called "engravings". Engraving is one of the oldest and most important techniques in printmaking. Wood engraving is a form of relief printing and is not covered in this article.

Woodcut is a relief printing technique in printmaking. An artist carves an image into the surface of a block of wood—typically with gouges—leaving the printing parts level with the surface while removing the non-printing parts. Areas that the artist cuts away carry no ink, while characters or images at surface level carry the ink to produce the print. The block is cut along the wood grain. The surface is covered with ink by rolling over the surface with an ink-covered roller (brayer), leaving ink upon the flat surface but not in the non-printing areas.

Monotyping is a type of printmaking made by drawing or painting on a smooth, non-absorbent surface. The surface, or matrix, was historically a copper etching plate, but in contemporary work it can vary from zinc or glass to acrylic glass. The image is then transferred onto a paper by pressing the two together, using a printing-press, brayer, baren or by techniques such as rubbing with the back of a wooden spoon or the fingers which allow pressure to be controlled selectively. Monotypes can also be created by inking an entire surface and then, using brushes or rags, removing ink to create a subtractive image, e.g. creating lights from a field of opaque colour. The inks used may be oil or water-based. With oil-based inks, the paper may be dry, in which case the image has more contrast, or the paper may be damp, in which case the image has a 10 percent greater range of tones.

Drypoint is a printmaking technique of the intaglio family, in which an image is incised into a plate with a hard-pointed "needle" of sharp metal or diamond point. In principle, the method is practically identical to engraving. The difference is in the use of tools, and that the raised ridge along the furrow is not scraped or filed away as in engraving. Traditionally the plate was copper, but now acetate, zinc, or plexiglas are also commonly used. Like etching, drypoint is easier to master than engraving for an artist trained in drawing because the technique of using the needle is closer to using a pencil than the engraver's burin.

Aquatint is an intaglio printmaking technique, a variant of etching that produces areas of tone rather than lines. For this reason it has mostly been used in conjunction with etching, to give both lines and shaded tone. It has also been used historically to print in colour, both by printing with multiple plates in different colours, and by making monochrome prints that were then hand-coloured with watercolour.

An artist's proof is an impression of a print taken in the printmaking process to see the current printing state of a plate while the plate is being worked on by the artist. A proof may show a clearly incomplete image, often called a working proof or trial impression, but in modern practice is usually used to describe an impression of the finished work that is identical to the numbered copies. There can also be printer's proofs which are taken for the printer to see how the image is printing, or are final impressions the printer is allowed to keep; but normally the term "artist's proof" would cover both cases.

In printmaking, an edition is a number of prints struck from one plate, usually at the same time. This may be a limited edition, with a fixed number of impressions produced on the understanding that no further impressions (copies) will be produced later, or an open edition limited only by the number that can be sold or produced before the plate wears. Most modern artists produce only limited editions, normally signed by the artist in pencil, and numbered as say 67/100 to show the unique number of that impression and the total edition size.

Intaglio is the family of printing and printmaking techniques in which the image is incised into a surface and the incised line or sunken area holds the ink. It is the direct opposite of a relief print where the parts of the matrix that make the image stand above the main surface.

Monoprinting is a type of printmaking where the intent is to make unique prints, that may explore an image serially. Other methods of printmaking create editioned multiples, the monoprint is editioned as 1 of 1. There are many techniques of mono-printing, in particular the monotype. Printmaking techniques which can be used to make mono-prints include lithography, woodcut, and etching.

The etching revival was the re-emergence and invigoration of etching as an original form of printmaking during the period approximately from 1850 to 1930. The main centres were France, Britain and the United States, but other countries, such as the Netherlands, also participated. A strong collector's market developed, with the most sought-after artists achieving very high prices. This came to an abrupt end after the 1929 Wall Street crash wrecked what had become a very strong market among collectors, at a time when the typical style of the movement, still based on 19th-century developments, was becoming outdated.

Line engraving is a term for engraved images printed on paper to be used as prints or illustrations. The term is mainly used in connection with 18th- or 19th-century commercial illustrations for magazines and books or reproductions of paintings. It is not a technical term in printmaking, and can cover a variety of techniques, giving similar results.

Viscosity printing is a multi-color printmaking technique that incorporates principles of relief printing and intaglio printing. It was pioneered by Stanley William Hayter.

An old master print is a work of art produced by a printing process within the Western tradition. The term remains current in the art trade, and there is no easy alternative in English to distinguish the works of "fine art" produced in printmaking from the vast range of decorative, utilitarian and popular prints that grew rapidly alongside the artistic print from the 15th century onwards. Fifteenth-century prints are sufficiently rare that they are classed as old master prints even if they are of crude or merely workmanlike artistic quality. A date of about 1830 is usually taken as marking the end of the period whose prints are covered by this term.

Daniel Hopfer was a German artist who is widely believed to have been the first to use etching in printmaking, at the end of the fifteenth century. He also worked in woodcut. Although his etchings were widely ignored by art historians for years, more recent scholarship is crediting him and his work with "single-handedly establishing the salability of etchings" and introducing the print publisher business model.

The Battle of the Nudes or Battle of the Naked Men, probably dating from 1465–1475, is an engraving by the Florentine goldsmith and sculptor Antonio del Pollaiuolo which is one of the most significant old master prints of the Italian Renaissance. The engraving is large at 42.4 x 60.9 cm, and depicts five men wearing headbands and five men without, fighting in pairs with weapons in front of a dense background of vegetation.

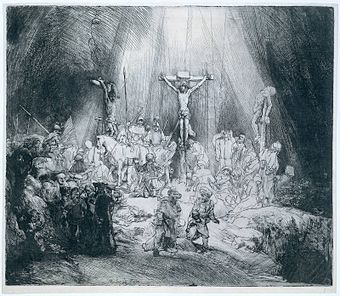

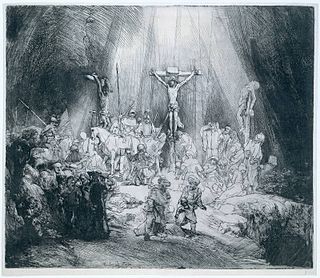

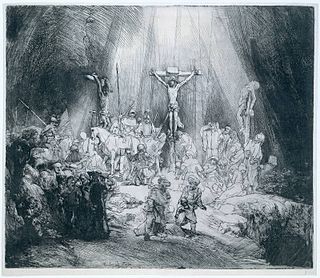

The Hundred Guilder Print is an etching by Rembrandt. The etching's popular name derives from the large sum of money supposedly once paid for an example. It is also called Christ healing the sick, Christ with the Sick around Him, Receiving Little Children, or Christ preaching, since the print depicts multiple events from Matthew 19, including Christ healing the sick, debating with scholars and calling on children to come to him. The rich young man mentioned in the chapter is leaving through the gateway on the right.

À la poupée is a largely historic intaglio printmaking technique for making colour prints by applying different ink colours to a single printing plate using ball-shaped wads of cloth, one for each colour. The paper has just one run through the press, but the inking needs to be carefully re-done after each impression is printed. Each impression will usually vary at least slightly, and sometimes very significantly.

In printmaking, surface tone, or surface-tone, is produced by deliberately or accidentally not wiping all the ink off the surface of the printing plate, so that parts of the image have a light tone from the film of ink left. Tone in printmaking meaning areas of continuous colour, as opposed to the linear marks made by an engraved or drawn line. The technique can be used with all the intaglio printmaking techniques, of which the most important are engraving, etching, drypoint, mezzotint and aquatint. It requires individual attention on the press before each impression is printed, and is mostly used by artists who print their own plates, such as Rembrandt, "the first master of this art", who made great use of it.