Year 1551 (MDLI) was a common year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar.

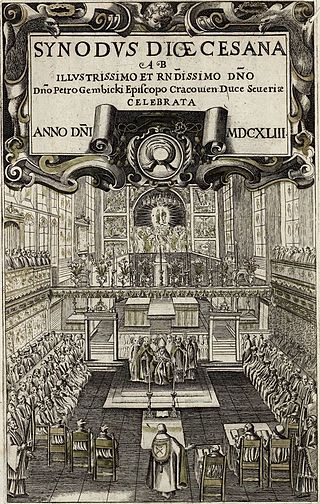

A synod is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word synod comes from the Ancient Greek σύνοδος 'assembly, meeting'; the term is analogous with the Latin word concilium'council'. Originally, synods were meetings of bishops, and the word is still used in that sense in Catholicism, Oriental Orthodoxy and Eastern Orthodoxy. In modern usage, the word often refers to the governing body of a particular church, whether its members are meeting or not. It is also sometimes used to refer to a church that is governed by a synod.

Nikon, born Nikita Minin was the seventh Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus' of the Russian Orthodox Church, serving officially from 1652 to 1666. He was renowned for his eloquence, energy, piety and close ties to Tsar Alexis of Russia. Nikon introduced many reforms, including liturgical reforms that were unpopular among conservatives. These divisions eventually led to a lasting schism known as Raskol (schism) in the Russian Orthodox Church. For many years, he was a dominant political figure, often equaling or even overshadowing the Tsar. In December 1667, Nikon was tried by a synod of church officials, deprived of all his sacerdotal functions, and reduced to the status of a simple monk.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1551.

Old Believers, also called Old Ritualists, are Eastern Orthodox Christians who maintain the liturgical and ritual practices of the Russian Orthodox Church as they were before the reforms of Patriarch Nikon of Moscow between 1652 and 1666. Resisting the accommodation of Russian piety to the contemporary forms of Greek Orthodox worship, these Christians were anathematized, together with their ritual, in a Synod of 1666–67, producing a division in Eastern Europe between the Old Believers and those who followed the state church in its condemnation of the Old Rite. Russian speakers refer to the schism itself as raskol (раскол), etymologically indicating a "cleaving-apart".

The Schism of the Russian Church, also known as Raskol, was the splitting of the Russian Orthodox Church into an official church and the Old Believers movement in the mid-17th century. It was triggered by the reforms of Patriarch Nikon in 1653, which aimed to establish uniformity between Greek and Russian church practices. Nikon had been a part of a group known as the Zealots of Piety in the 1630s and 1640s, a circle of church reformers whose acts included amending service books in accordance with the "correct" Russian tradition. When Nikon became Patriarch in 1652, he continued the practice of amending books under the guidance of Greek Orthodox advisors, now changing practices in the Russian Church to align with the Greek rite. This act, along with the acceptance of the Nikonian reforms by Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich and the state, led to the rupture between Old Believers and the newly reformed church and state.

In several of the autocephalous Eastern Orthodox churches and Eastern Catholic Churches, the patriarch or head bishop is elected by a group of bishops called the Holy Synod. For instance, the Holy Synod is a ruling body of the Georgian Orthodox Church.

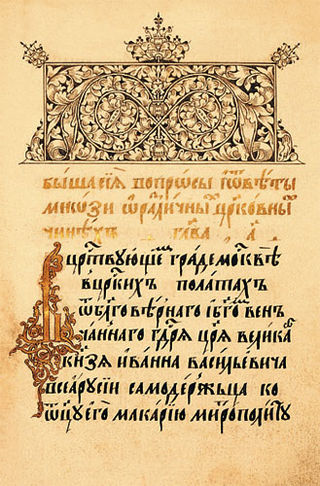

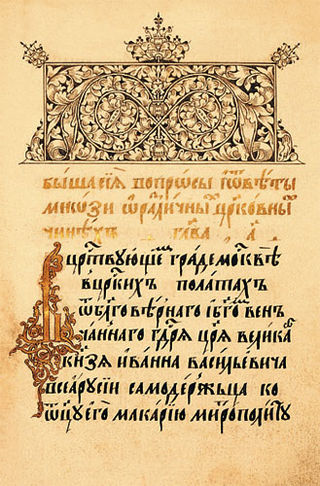

The Book of One Hundred Chapters, also called Stoglav (Стоглав) in Russian, is a collection of decisions of the Russian church council of 1551 that regulated the canon law and ecclesiastical life in the Tsardom of Russia, especially the everyday life of the Russian clergy.

The Metropolis of Moscow and all Russia was a metropolis that was unilaterally erected by hierarchs of the Eastern Orthodox Church in the territory of the Grand Duchy of Moscow in 1448. The first metropolitan was Jonah of Moscow; he was appointed without the approval of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. The metropolis split from the Metropolis of Kiev and all Rus' because the previous metropolitan — Isidore of Kiev — had accepted the Union of Florence. Seventeen prelates succeeded Jonah until Moscow's canonical status was regularised in 1589 with the recognition of Job by the Ecumenical Patriarch. Job was also raised to the status of patriarch and was the first Patriarch of Moscow. The Moscow Patriarchate was a Caesaropapist entity that was under the control of the Russian state. The episcopal seat was the Dormition Cathedral in Moscow.

The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, also called Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia or ROCOR, or Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA), is a semi-autonomous part of the Russian Orthodox Church. Currently, the position of First-Hierarch of the ROCOR is occupied by Metropolitan Nicholas (Olhovsky).

Joasaphus I was the fifth Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia (1634–1640).

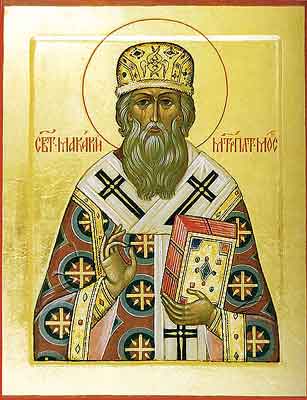

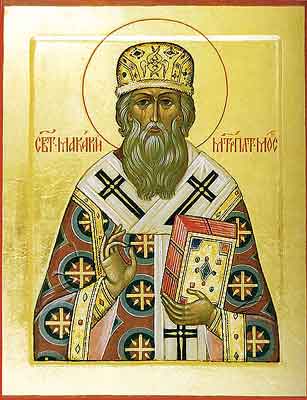

Macarius was the Metropolitan of Moscow and all Rus' from 1542 until 1563. He was the tenth metropolitan in Moscow to be appointed without the approval of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople as had been the norm.

The Russian Orthodox Church is traditionally said to have been founded by Andrew the Apostle, who is thought to have visited Scythia and Greek colonies along the northern coast of the Black Sea. According to one of the legends, St. Andrew reached the future location of Kiev and foretold the foundation of a great Christian city. The spot where he reportedly erected a cross is now marked by St. Andrew's Cathedral.

The Church Reform of Peter the Great was a set of changes Tsar Peter I introduced to the Russian Orthodox Church, especially to church government. Issued in the context of Peter's overall westernizing reform programme, it replaced the Patriarch of Moscow with the Holy Synod and made the church effectively a department of state.

The Great Moscow Synod was a Pan-Orthodox synod convened by Tsar Alexis of Russia in Moscow in April 1666 in order to depose Patriarch Nikon of Moscow.

Patriarch MacariusIII Ibn al-Za'im was Patriarch of Antioch from 1647 to 1672. He led a period of blossoming of his Church and is also remembered for his travels in Russia and for his involvement in the reforms of Russian Patriarch Nikon.

In the Russian Empire, government agencies exerted varying levels of control over the content and dissemination of books, periodicals, music, theatrical productions, works of art, and motion pictures. The agency in charge of censorship in the Russian Empire changed over time. In the early eighteenth century, the Russian emperor had direct control, but by the end of the eighteenth century, censorship was delegated to the Synod, the Senate, and the Academy of Sciences. Beginning in the nineteenth century, it fell under the charge of the Ministry of Education and finally the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

The schism between the Ecumenical Patriarchate and part ofitsMetropolis of Kiev and all Rus occurred between approximately 1467 and 1560. This schism de facto ended supposedly around 1560.

The Accession of Kyiv Metropolis to Moscow Patriarchate was the transferance of the Metropolis of Kiev, Galicia and all Rus' in the Eastern Orthodox from the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople to the Patriarchate of Moscow. The metropolis lay in the territory of the Cossack Hetmanate and of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.