The Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas was a Spanish political party in the Second Spanish Republic. A Catholic conservative force, it was the political heir to Ángel Herrera Oria's Acción Popular and defined itself in terms of the 'affirmation and defence of the principles of Christian civilization,' translating this theoretical stand into a political demand for the revision of the anti-Catholic passages of the republican constitution. CEDA saw itself as a defensive organisation, formed to protect religious toleration, family, and private property rights. José María Gil-Robles declared his intention to "give Spain a true unity, a new spirit, a totalitarian polity..." and went on to say "Democracy is not an end but a mean to achieve the conquest of the new state. When the time comes, either parliament submits or we will eliminate it." The CEDA held Fascist-style rallies, called Gil-Robles "Jefe", the Castillian Spanish equivalent to Duce, and sometimes debated whether CEDA might lead a "March on Madrid" to forcefully seize power.

Alejandro Lerroux García was a Spanish politician who was the leader of the Radical Republican Party. He served as Prime Minister three times from 1933 to 1935 and held several cabinet posts as well. A highly charismatic politician, he was distinguished by his demagogical and populist political style.

The Pact of San Sebastián was a meeting led by Niceto Alcalá Zamora and Miguel Maura, which took place in San Sebastián, Spain on 17 August 1930. Representatives from practically all republican political movements in Spain at the time attended the meeting. Presided over by Fernando Sasiaín, the attendees included:

Manuel Portela y Valladares was a Spanish political figure during the Second Spanish Republic. He served as the 43rd Attorney General of Spain between 1912 and 1913.

Niceto Alcalá-Zamora y Torres was a Spanish lawyer and politician who served, briefly, as the first prime minister of the Second Spanish Republic, and then—from 1931 to 1936—as its president.

José María Gil-Robles y Quiñones de León was a Spanish politician, leader of the CEDA and a prominent figure in the period leading up to the Spanish Civil War. He served as Minister of War from May to December 1935. In the 1936 elections the CEDA was defeated, and support for Gil-Robles and his party evaporated. Gil-Robles was unwilling to struggle with Francisco Franco for power and in April 1937 he announced the dissolution of CEDA, and went into exile. Abroad, he negotiated with Spanish monarchists to try to arrive at a common strategy for taking power in Spain. In 1968 he was named a professor of the University of Oviedo and published his book No fue posible la paz . After the death of Franco and the end of his regime, Gil-Robles became one of the leaders of the "Spanish Christian Democracy" party, which however failed to win support in the Spanish general elections in 1977.

The Spanish Republic, commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic, was the form of democratic government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931 after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII. It was dissolved on 1 April 1939 after surrendering in the Spanish Civil War to the Nationalists led by General Francisco Franco.

The Radical Republican Party, sometimes shortened to the Radical Party, was a Spanish Radical party in existence between 1908 and 1936. Beginning as a splinter from earlier Radical parties, it initially played a minor role in Spanish parliamentary life, before it came to prominence as one of the leading political forces of the Spanish Republic.

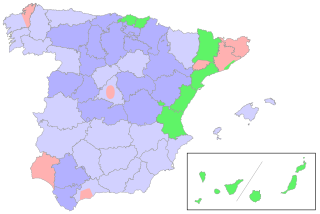

Legislative elections were held in Spain on 16 February 1936. At stake were all 473 seats in the unicameral Cortes Generales. The winners of the 1936 elections were the Popular Front, a left-wing coalition of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE), Republican Left (Spain) (IR), Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC), Republican Union (UR), Communist Party of Spain (PCE), Acció Catalana (AC), and other parties. Their coalition commanded a narrow lead over the divided opposition in terms of the popular vote, but a significant lead over the main opposition party, Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (CEDA), in terms of seats. The election had been prompted by a collapse of a government led by Alejandro Lerroux, and his Radical Republican Party. Manuel Azaña would replace Manuel Portela Valladares, caretaker, as prime minister.

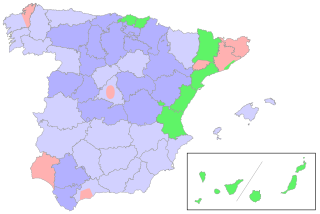

Elections to Spain's legislature, the Cortes Generales, were held on 19 November 1933 for all 473 seats in the unicameral Cortes of the Second Spanish Republic. Since the previous elections of 1931, a new constitution had been ratified, and the franchise extended to more than six million women. The governing Republican-Socialist coalition had fallen apart, with the Radical Republican Party beginning to support a newly united political right.

The 1931 Spanish general election for the Constituent Cortes was the first such election held in the Second Republic. It took place in several rounds.

Ricardo Samper Ibáñez was a Spanish political figure during the Second Spanish Republic.

The Liberal Republican Right was a Spanish political party led by Niceto Alcalá-Zamora, which combined immediately with the incipient republican formation of Miguel Maura just before the Pact of San Sebastián, of which they formed a part, as Alcalá-Zamora was elected president of the Provisional Government of the Republic. After the proclamation of the republic, it participated in the 1931 general election among the lists of the combined republican-socialist coalition, receiving 22 seats.

The background of the Spanish Civil War dates back to the end of the 19th century, when the owners of large estates, called latifundios, held most of the power in a land-based oligarchy. The landowners' power was unsuccessfully challenged by the industrial and merchant sectors. In 1868 popular uprisings led to the overthrow of Queen Isabella II of the House of Bourbon. In 1873 Isabella's replacement, King Amadeo I of the House of Savoy, abdicated due to increasing political pressure, and the short-lived First Spanish Republic was proclaimed. After the restoration of the Bourbons in December 1874, Carlists and anarchists emerged in opposition to the monarchy. Alejandro Lerroux helped bring republicanism to the fore in Catalonia, where poverty was particularly acute. Growing resentment of conscription and of the military culminated in the Tragic Week in Barcelona in 1909. After the First World War, the working class, the industrial class, and the military united in hopes of removing the corrupt central government, but were unsuccessful. Fears of communism grew. A military coup brought Miguel Primo de Rivera to power in 1923, and he ran Spain as a military dictatorship. Support for his regime gradually faded, and he resigned in January 1930. There was little support for the monarchy in the major cities, and King Alfonso XIII abdicated; the Second Spanish Republic was formed, whose power would remain until the culmination of the Spanish Civil War. Monarchists would continue to oppose the Republic.

The Revolution of 1934, also known as the Revolution of October 1934 or the Revolutionary General Strike of 1934, was an uprising during the "black biennium" of the Second Spanish Republic between 5 and 19 October 1934.

Events in the year 1933 in Spain.

Antonio Lara Zárate was a Spanish lawyer and politician. He was a member of the Congress of Deputies throughout the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939). He served as Minister of Finance (1933–34), Minister of Justice and Minister of Public Works . After the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) he went into exile in Mexico, where he died.

Rafael Salazar Alonso was a Spanish lawyer, newspaper proprietor and politician who engaged in left-wing and right-wing politics. He was the mayor of Madrid and a government minister. He was executed by the Republican authorities two months after the Spanish Civil War started.

The IndependentRadical Socialist Republican Party was a minor Spanish radical political party, created in 1929 after the split of the left-wing of the Radical Socialist Republican Party. Its main leaders were Marcelino Domingo, Álvaro de Albornoz and Ángel Galarza.

The Nombela scandal or Nombela affair was a corruption scandal during the Second Spanish Republic. The scandal had a serious political impact on the coalition government of the Radical Republican Party and CEDA, due to many distinguished members of the Republican Party, including its leader Alejandro Lerroux, being associated with it. The scandal, was one of the factors that contributed to the fall of the government and the 1936 elections. It took its name by the person who brought it into light, Antonio Nombela.