Plot summary

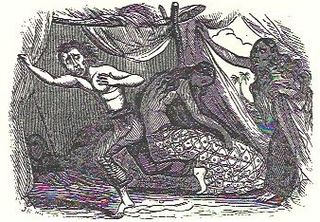

Upon landing in the ship's leaky boat, Riley and his crew began to make repairs to return to the ship, rather than face a desert rescue. The repairs were incomplete when a native armed with a spear arrived and helped himself to their meager supplies. After filling up his arms with what he could carry off, he left and returned with two others also carrying spears. Riley stayed back to distract the Arabs and give his men a chance to escape in the loaded and unfinished boat.

They made it, but without Riley, who offered his captors money in exchange for his life. With their agreement, crew member Antonio Michele swam to shore to pay them, at which point Riley ran out into the water to join his men. After Riley was safe in the boat, all he could do was watch while an Arab stabbed Michele in the stomach and dragged his body away, which caused Riley tremendous feelings of guilt.

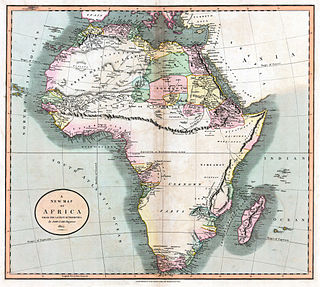

As the ship, still aground, was unusable, unable to reach what are now the islands of Cape Verde, the crew decided to sail to the South while hoping for rescue, which did not come. After nine days, out of food and water, they returned to the shore at an isolated beach 200 miles (320 km) further south, with the realization that they would probably be killed just as quickly as Michele. They reached the shore, which was surrounded by high cliffs. Riley told his men to begin digging for water. He climbed to the top of the cliffs and found himself staring at the edge of a vast expanse of flat desert.

His crew joined him, and together they started to walk inland hoping for rescue by a friendly tribe. But soon they were without hope, enduring 120 °F (49 °C) heat during the day and freezing temperatures at night. Out of food and water, Riley resolved that they should either accept death or offer themselves as slaves to the first tribe they encountered, which is exactly what happened.

A large gathering of men and camels appeared on the horizon, and the crew approached them. The tribe started to fight among themselves, to determine who would become the slave-owners. Riley's crew became separated when they were taken as slaves by different groups, which then went their own ways.

Riley recounts in his memoirs the terrifying days spent in servitude. After a while, he learned some of the language and was able to communicate in a rudimentary way. One day during his captivity some Arabs arrived seeking a trade with his master. Riley asked two of them, Sidi Hamet and his brother, if they would buy him and his fellow shipmates and bring them to the closest city - which was Mogador (now Essaouira) - hundreds of miles away to the north. Hamet was moved by Riley's desire to save his friends and agreed to buy them if Riley would pay him with cash and a gun when they arrived at the city. Riley promised that he had a friend there who would pay him upon their safe arrival, which was totally untrue, for Riley knew nobody. Hamet promised to slit his throat if he were lying. When the time came for Riley to write the note, he was terrified. How could he write a note to a perfect stranger, begging him for several hundred dollars? He had no choice. In the note he explained who he was and described his situation.

Traveling through the desert caused all to suffer - master and slave alike. There was little food for the already starving American men, and little water for everyone. Amazingly, they traveled the distance to the city - several hundred miles, constantly in fear of marauding hunter tribes. They were especially in fear of a father-in-law of one of the brothers, who was out to settle a dispute.

Eventually they arrived at the outskirts, and Hamet took the note, which was addressed to the town's consul, into town. Hamet met a young man in the city, who, it turns out, worked as an assistant to a British merchant who also acted as a kind of consul and agent. Hamet told this man about his "friend" and gave him the note. This consul, William Willshire, impressed by the sincerity of the note, agreed to pay. Willshire rode out in a group to meet the men as they waited outside the city, and Willshire greeted Riley with hugs and tears.

Riley sent his remaining men home to America but stayed behind for just a few days. Seti Hamet, his former master, promised to return to the desert to look for Riley's missing crew members. Riley went back to America and was reunited with his wife and their five children in Connecticut. Two of the missing men were later returned to the States, and Riley heard of two Arabs who were stoned to death out in the desert by marauders. He was convinced they were his former master, trying to keep his word, together with his brother.