Henry Hastings Sibley was a fur trader with the American Fur Company, the first U.S. Congressional representative for Minnesota Territory, the first governor of the state of Minnesota, and a U.S. military leader in the Dakota War of 1862 and a subsequent expedition into Dakota Territory in 1863.

The Battle of Big Mound was a United States Army victory in July 1863 over the Santee Sioux Indians allied with some Yankton, Yanktonai and Teton Sioux in Dakota Territory.

Little Crow III was a Mdewakanton Dakota chief who led a faction of the Dakota in a five-week war against the United States in 1862.

Camp Release State Monument is located on the edge of Montevideo, Minnesota, United States, just off Highway 212 in Lac qui Parle County, in the 6-acre Camp Release State Memorial Wayside. The Camp Release Monument stands as a reminder of Minnesota's early state history. The Minnesota River Valley and Montevideo were important sites in the Dakota War of 1862.

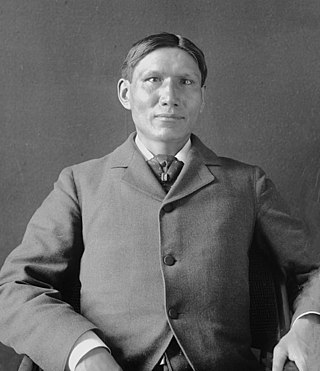

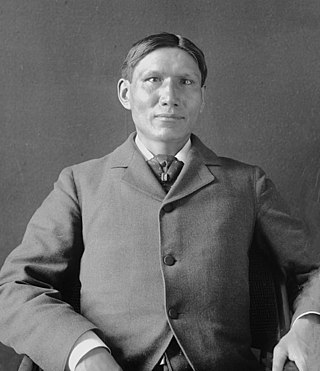

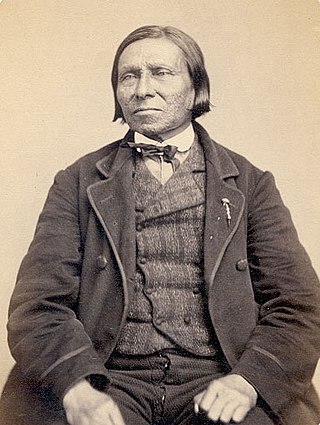

Big Eagle was the chief of a band of Mdewakanton Dakota in Minnesota. He played an important role as a military leader in the Dakota War of 1862. Big Eagle surrendered soon after the Battle of Wood Lake and was sentenced to death and imprisoned, but was pardoned by President Abraham Lincoln in 1864. Big Eagle's narrative, "A Sioux Story of the War" was first published in 1894, and is one of the most widely cited first-person accounts of the 1862 war in Minnesota from a Dakota point of view.

The Treaty of Traverse des Sioux was signed on July 23, 1851, at Traverse des Sioux in Minnesota Territory between the United States government and the Upper Dakota Sioux bands. In this land cession treaty, the Sisseton and Wahpeton Dakota bands sold 21 million acres of land in present-day Iowa, Minnesota and South Dakota to the U.S. for $1,665,000.

The Battle of Wood Lake occurred on September 23, 1862, and was the final battle in the Dakota War of 1862. The two-hour battle, which actually took place at nearby Lone Tree Lake, was a decisive victory for the U.S. forces led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley. With heavy casualties inflicted on the Dakota forces led by Chief Little Crow, the "hostile" Dakota warriors dispersed. Little Crow and 150 followers fled for the northern plains, while other Mdewakantons quietly joined the "friendly" Dakota camp started by the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands, which would soon become known as Camp Release.

The Battle of Birch Coulee occurred on September 2–3, 1862, and resulted in the heaviest casualties suffered by U.S. forces during the Dakota War of 1862. The battle occurred after a group of Dakota warriors followed a U.S. burial expedition, including volunteer infantry, mounted guards and civilians, to an exposed plain where they were setting up camp. That night, 200 Dakota soldiers surrounded the camp and ambushed the Birch Coulee campsite in the early morning, commencing a siege that lasted for over 30 hours, until the arrival of reinforcements and artillery led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley.

Kaposia or Kapozha was a seasonal and migratory Dakota settlement, also known as "Little Crow's village," once located on the east side of the Mississippi River in present-day Saint Paul, Minnesota. The Kaposia band of Mdewakanton Dakota was established in the late 18th century and led by a succession of chiefs known as Little Crow or "Petit Corbeau." After a flood in 1826, the band moved to the west side of the river, about nine miles below Fort Snelling.

The Attack at the Lower Sioux Agency was the first organized attack led by Dakota leader Little Crow in Minnesota on August 18, 1862, and is considered the initial engagement of the Dakota War of 1862. It resulted in 13 settler deaths, with seven more killed while fleeing the agency for Fort Ridgely.

The Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising, the Dakota Uprising, the Sioux Outbreak of 1862, the Dakota Conflict, or Little Crow's War, was an armed conflict between the United States and several eastern bands of Dakota collectively known as the Santee Sioux. It began on August 18, 1862, when the Dakota, who were facing starvation and displacement, attacked white settlements at the Lower Sioux Agency along the Minnesota River valley in southwest Minnesota. The war lasted for five weeks and resulted in the deaths of hundreds of settlers and the displacement of thousands more. In the aftermath, the Dakota people were exiled from their homelands, forcibly sent to reservations in the Dakotas and Nebraska, and the State of Minnesota confiscated and sold all their remaining land in the state. The war also ended with the largest mass execution in United States history with the hanging of 38 Dakota men.

The Dakota are a Native American tribe and First Nations band government in North America. They compose two of the three main subcultures of the Sioux people, and are typically divided into the Eastern Dakota and the Western Dakota.

Joseph Renville (1779–1846) was an interpreter, translator, expedition guide, Canadian officer in the War of 1812, founder of the Columbia Fur Company, and an important figure in dealings between settlers of European ancestry and Dakota (Sioux) Natives in Minnesota. He contributed to the translation of Christian religious texts into the Dakota language. The hymnal Dakota dowanpi kin, was "composed by J. Renville and sons, and the missionaries of the A.B.C.F.M." and was published in Boston in 1842. Its successor, Dakota Odowan, first published with music in 1879, has been reprinted many times and is in use today.

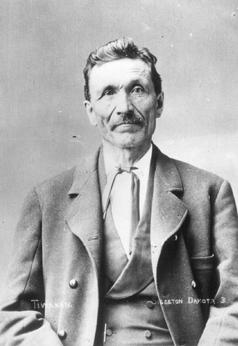

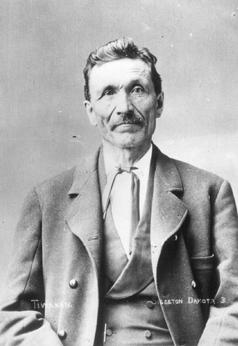

Gabriel Renville, also known as Ti'wakan, was a US-government appointed chief of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate Sioux Tribe from 1866 until his death in 1892. He opposed conflict with the United States during the Dakota War of 1862 and was a driving force within the Dakota Peace Party. In 1863, Renville volunteered to serve as a Dakota scout serving in US military leader Henry Hastings Sibley's punitive expedition against Dakota escapees, hunting those considered "hostile" including Little Crow. Renville would become chief and superintendent of scouts in 1864. Gabrielle Renville's influence and political leadership were critical to the eventual creation of the Lake Traverse Indian Reservation, which lies mainly in present-day South Dakota.

Joseph Renshaw Brown (1805–1870) was an American politician, pioneer, fur trader, newspaper editor, businessman, inventor, speculator, and Indian agent who was prominent in Minnesota and Wisconsin territorial and state politics for over 50 years.

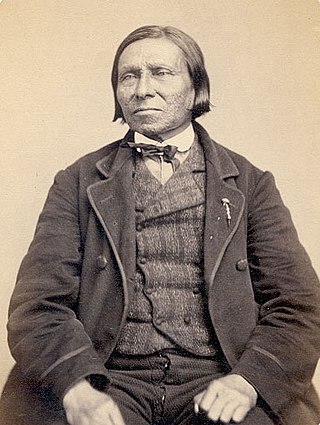

Wabasha III (Wapahaśa) was a prominent Dakota Sioux chief, also known as Joseph Wabasha. He succeeded his father as head chief of the Mdewakanton Dakota in 1836. Following the Dakota War of 1862 and the forced removal of the Dakota to Crow Creek Reservation, Wabasha became known as head chief of the Santee Sioux. In the final years of his life, Chief Wabasha helped his people rebuild their lives at the Santee Reservation in Nebraska.

Acton is an unincorporated community in Acton Township, Meeker County, Minnesota, United States, near Grove City and Litchfield. The community is located along Meeker County Road 23 near State Highway 4. County Road 32 is also in the immediate area.

Snana, also known as Maggie Brass, was a Mdewakanton Dakota woman who rescued and protected a fourteen-year-old German girl, Mary Schwandt, after she was taken captive during the Dakota War of 1862. She was reunited with Mary Schwandt Schmidt in 1894, leading to a feature article in the St. Paul Pioneer Press. Snana’s narrative of the war, “Narration of a Friendly Sioux,” was edited by historian Return Ira Holcombe and published in 1901.

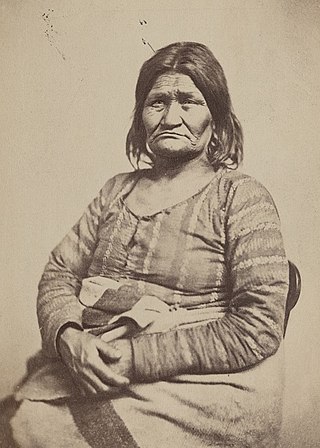

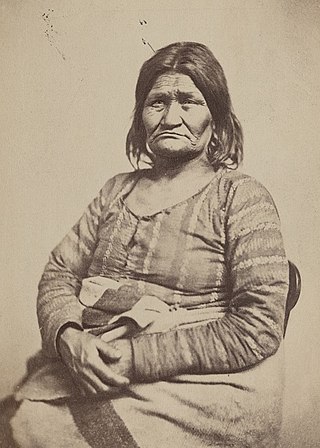

Azayamankawin, also known as Hazaiyankawin, Betsey St. Clair, Old Bets, or Old Betz, was one of the most photographed Native American women of the 19th century. She was a Mdewakanton Dakota woman well known in Saint Paul, Minnesota, where she once ran a canoe ferry service. Old Bets was said to have helped many women and children taken captive during the Dakota War of 1862.

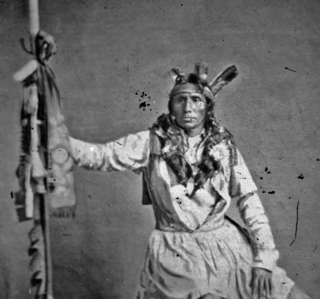

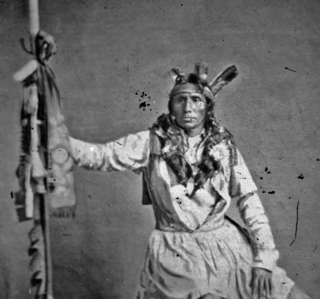

Shakopee III was a Mdewakanton Dakota chief who was involved at the start of the Dakota War of 1862. Born Eatoka, which means "Another Language," he became known as Shakpedan or Little Six after the death of his father in 1860.