Susan B. Anthony was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to social equality, she collected anti-slavery petitions at the age of 17. In 1856, she became the New York state agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Olympia Brown was an American minister and suffragist. She was the first woman to be ordained as clergy with the consent of her denomination. Brown was also an articulate advocate for women's rights and one of the few first generation suffragists who were able to vote with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Its membership, which was about seven thousand at the time it was formed, eventually increased to two million, making it the largest voluntary organization in the nation. It played a pivotal role in the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which in 1920 guaranteed women's right to vote.

Women's suffrage, or the right to vote, was established in the United States over the course of more than half a century, first in various states and localities, sometimes on a limited basis, and then nationally in 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution.

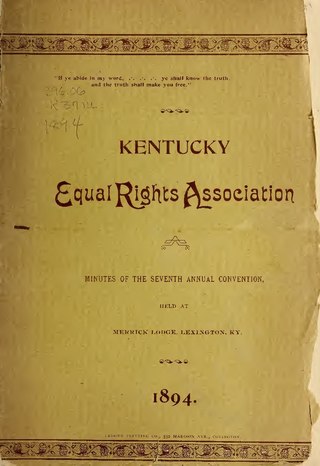

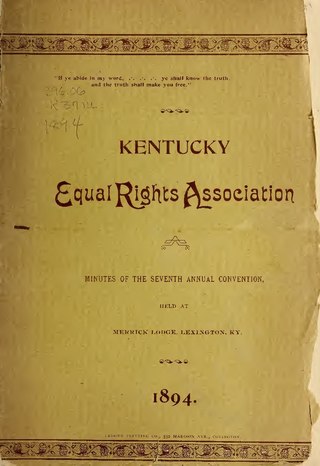

Laura Clay was an American suffragist, politician and orator who served as co-founder and first president of the Kentucky Equal Rights Association, was a leader of the American women's suffrage movement. She was one of the most important suffragists in the South, favoring the states' rights approach to suffrage. A powerful orator, she was active in the Democratic Party and had important leadership roles in local, state and national politics. In 1920 at the Democratic National Convention, she was one of two women, alongside Cora Wilson Stewart, to be the first women to have their names placed into nomination for the presidency at the convention of a major political party.

Mary Barr Clay was a leader of the American women's suffrage movement. She also was known as Mary B. Clay and Mrs. J. Frank Herrick.

The Heyburn Building is a 17-floor, 250-foot (76-m) building in downtown Louisville, Kentucky, United States. In the early 20th century, it was an integral part of the "magic corner" of Fourth Street and Broadway, which rivaled Main Street as Louisville's business district. It occupies the lot that was the location of the Avery mansion, home of Louisville suffragist, Susan Look Avery. This block of West Broadway had been a posh residential corridor prior to the commercial transition of which the Heyburn Building composed a part.

The Woman's Bible is a two-part non-fiction book, written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and a committee of 26 women, published in 1895 and 1898 to challenge the traditional position of religious orthodoxy that woman should be subservient to man. By producing the book, Stanton wished to promote a radical liberating theology, one that stressed self-development. The book attracted a great deal of controversy and antagonism at its introduction.

Kentucky Equal Rights Association (KERA) was the first permanent statewide women's rights organization in Kentucky. Founded in November 1888, the KERA voted in 1920 to transmute itself into the Kentucky League of Women Voters to continue its many and diverse progressive efforts on behalf of women's rights.

Emma Smith DeVoe was an American women suffragist in the early twentieth century, changing the face of politics for both women and men alike. When she died, the Tacoma News Tribune called her Washington state's "Mother of Women's Suffrage".

This timeline highlights milestones in women's suffrage in the United States, particularly the right of women to vote in elections at federal and state levels.

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

Lydia Arms Avery Coonley-Ward was a social leader, clubwoman and writer. Coonley served as a president of the Chicago Women's Club and was known for her poetry. She also helped her second husband, Henry Augustus Ward, grow his meteorite collection.

Lucy Elmina Anthony was an internationally known leader in the American woman's suffrage movement. She was the niece of American social reformer and women's rights activist, Susan B. Anthony, and longtime companion of women's suffrage leader, Anna Howard Shaw. She served as a secretary to both women, as well as on the committee on local arrangements for the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA)

Oreola Williams Haskell was an American activist for suffrage, author, and poet in the early twentieth century.

The women's suffrage movement began in California in the 19th century and was successful with the passage of Proposition 4 on October 10, 1911. Many of the women and men involved in this movement remained politically active in the national suffrage movement with organizations such as the National American Women's Suffrage Association and the National Woman's Party.

Mary Jane Warfield Clay was an American socialite, suffragist, abolitionist, and political activist. An early leader in the suffrage movement in Kentucky, she began by forming a suffrage club at her home in 1879. Her experience and success as a farm manager included her acute business sense in the middle of the American Civil War, like selling supplies from her farm to both Union and Confederate forces when they each occupied the Commonwealth. Her most active work in the suffrage movement was to encourage and support her daughters who would become the most well known Kentucky suffragists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Elise Clay Bennett Smith was President of the Kentucky Equal Rights Association from 1915 to 1916, and served as an Executive Committee member for the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Her last name changed several times as she married three men in succession: from her birth surname of Bennett she became Smith, then Jefferson, and finally Gagliardini.

Mary Elizabeth Simpson Sperry was a leading California suffragist who served as president of the California Woman Suffrage Association.

Alice Barbee Castleman was an American social leader, philanthropist, and suffragist. She was known throughout the country for her activities in political and civic endeavors.