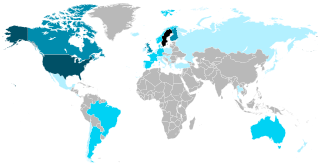

The Swedish Emigration Commission (Swedish : Emigrationsutredningen), was a commission that existed between 1907 and 1913 that was mandated by the Swedish Riksdag to try to reduce Swedish emigration to the United States. In the 19th century, Sweden had had one of the highest rates of emigration to North America in all of Europe, the third highest after Ireland and Norway. By 1910, one fifth of all Swedes had their homes in America. [1] The situation alarmed conservative Swedes, who regarded emigration as a challenge to national solidarity and to the very nation state itself, already seemingly under threat from trade unionism and the international socialist movement. [2] The liberal interest, which had in the 19th century favored emigration as a practical necessity, by now also saw it as a net drain, depriving Sweden of the labor necessary for economic development. Both camps shared a perception, disturbing in a Europe where the forces of war were gathering, that young, male Swedes were fleeing to America to escape military service. [3]

The conservative and nationalist parties proposed dealing with the problem by restrictions, the liberal and Social Democrat parties by social and economic reform. Despite such ideological faultlines, it was with broad national consensus that a Parliamentary Emigration Commission was mandated to study the problem in 1907. Led by the liberal academic Gustav Sundbärg, the Commission went to work with "characteristic Swedish thoroughness", [4] and published its findings in 21 volumes of exhaustive data on social and economic conditions in Sweden and America, together with Sundbärg's analysis and proposals. As Sundbärg put it, to discuss the emigration meant to discuss Sweden in its entirety. [4] The conservative parties proposed legal restrictions on emigration propaganda, emigrant agents, and emigration by military conscripts. In the end, all such authoritarian measures were dismissed by the Commission, which instead went with Sundbärg's goal of bringing the best sides of America to Sweden (unsurprisingly, as Sundbärg himself wrote the conclusions). [5] First on his list of urgent reforms were universal male suffrage, better housing, general economic development, and a broader popular education which could counteract "class and caste differences." [6]

Class inequality in the hierarchic Swedish society was a strong theme in the findings of the Commission. It appeared as a major motivating force in the summarized case histories of outbound Swedish emigrants, interviewed in Hull and Liverpool, which were published in Volume VII. The motif was also typical of the personal documents—of greater human and research interest today—which were included in the same volume. Those were narratives submitted by anonymous Swedes in Canada and the US in response to solicitations by the Commission in Swedish-American newspapers. 289 of them were also published in Volume VII, with the individuals identified by initials, state of residence, and year of emigration. Barton warns that, statistically, the response to the Commission's newspaper appeal will be slanted towards individuals with particularly strong views; yet their experiences remain illuminating. [7] The great majority were enthusiastic over their new homeland, and critical of conditions in Sweden. They describe particularly the grim poverty in the Swedish countryside, the hard work, pitiful wages, and discouraging prospects. One woman wrote from North Dakota of how in her Värmland home parish, she had had to go out and earn her living in peasant households from the age of eight, starting work at four in the morning and living on "rotten herring and potatoes, served out in small amounts so that I would not eat myself sick." She could see "no hope of saving anything in case of illness, but rather I could see the poorhouse waiting for me in the distance." When she was seventeen, her emigrated brothers sent her a prepaid ticket to America, and "the hour of freedom struck." [8] The emigrants also strongly emphasized non-material considerations, such as the exclusion of the poor from the political process, through the restrictive Swedish franchise before 1907. Bitter experiences of Swedish class snobbery still rankled after sometimes 40–50 years in America. A man who'd emigrated in 1868 described the disparaging comments he had heard in his youth from the aristocrat in charge of the parish poor relief, which "gave rise to great bitterness and a large number, among them myself, emigrated to America, which I have never regretted. Here, you are treated like a human being, wherever you are." [9]

A year after the Commission published its last volume, World War I broke out and reduced emigration to a mere trickle. There was a brief upswing after the war, but from the mid-1920s, there was no longer any Swedish mass emigration. Did the ambitious Emigration Commission have any part in solving the problem? Franklin D. Scott argued in an influential essay in 1965 that it had very little, and that the American Immigration Act of 1924 was the effective cause. Barton, by contrast, points to the rapid implementation of essentially all the Commission's recommendations, from industrialization to an array of social reforms, and maintains that its findings "must have had a powerful cumulative effect upon Sweden's leadership and broader public opinion." [10]