Legend

The legend of Swift's silver mine is based on accounts given in the journal of an Englishman named Jonathan Swift. Swift claimed to have preceded Daniel Boone into Kentucky, coming to the region in 1760 on a series of mining expeditions. [2] The journal recounts how a wounded bear led Swift to a vein of silver ore in a cave, and how that for the next nine years, he made annual treks back to the site of the mine, carrying out "silver bars and minted coins." [2] An article in an 1886 edition of Harper's Magazine tells how Swift supposedly buried a good deal of the treasure at various locations:

John Swift said he made silver in large quantities, burying some thirty thousand dollars and crowns on a large creek; fifteen thousand dollars a little way off, near some trees, which were duly marked; a prize of six thousand dollars close by the fork of a white oak; and three thousand dollars in the rocks of a rock house: all which, in the light of these notes, it is allowed any one who will to hunt for. [3]

Later, amid numerous obstacles that included Indian attacks, and a mutiny by his crew, Swift walled up the cave and discontinued his mining operation. [2] He left his journal in the possession of a Mrs. Renfro, the widow of one Joseph Renfro of Bean's Station, Tennessee, in whom he was purported to have a romantic interest. [4] Before Swift could return to the mine, he was stricken blind and was unable to locate it again. [2]

Variations

Settlers in Wise County, Virginia, believed that the mine was located on or around Stone Mountain, and that local Indians knew the location of the mine. According to the settlers, an Indian chief named Benge once said that "if the pale face knew what he knew they could shoe their horses cheaper with silver than with iron." They maintain that a captured settler named Hans G. Frenchman was taken to the mine by the Indians. He marked its location, and later escaped his captors and revealed the location of the mine to Swift. In this version of the story, Swift and Frenchman took only enough silver to buy two horses, and on a return trip, were unable to locate the mine. [5]

Another variation along these lines holds that Swift was taken to the mine by a Frenchman named "Monday" or "Monde". In this version, Swift and Monde are driven from the mine by an Indian attack, and Swift kills Monde for fear that he will reveal the location of the mine to others. Later, when Swift attempts to return to the mine, Monde's hand covers the compass so he cannot tell which direction to proceed. [6]

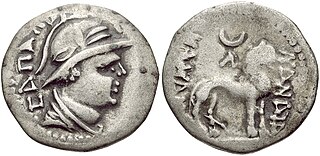

Solomon Mullins, or "Money-making Sol" (born 1782, died 1858) was rumored to have discovered Swift's mines near Pine Mountain in Southwest Virginia. Solomon lived in what was then known as Holly Creek, but is now Clintwood, Virginia. Solomon melted the silver down and used one of his slaves to "strike" for him (striking: the head of a hammer is heated until it is a plastic state and struck over a good coin. The coin, being harder than the softened head of the hammer is, therefore, imprinted. The hammer is then allowed to cool thus producing the die). To finish the process, or to imprint the counterfeit coins with official markings, Sol and his slave would relocate to the privacy afforded by caves located on cliffs adjacent Sol's farm. To this day, the cliffs are known as "Sol's Cliffs".

According to local legend, Solomon's "counterfeit" money used more silver, and was worth more, than the official currency at the time. Apparently, Sol mixed the pure silver with other lesser metals to make his money. Solomon never disclosed where he obtained the pure silver, but many people speculated that he found the silver in one of the many caves on Pine Mountain close to his farm.

Once, Solomon was caught by a U.S. detective while at work in the cliffs. Reportedly, realizing his predicament, he ordered the man to help with his work, saying "Grab a hammer and strike this." He hoped the action, if taken, would make the detective complicit; regardless of the story's veracity, it did not do Sol any good. In early 1837, Solomon and two of his 10 children, Peter and Spencer, were brought to trial and were charged with making counterfeit coins. Solomon was found guilty, but fled Virginia before being sentenced. He reportedly died in 1858 and never revealed the location of his source of silver.

Each year in Wolfe County, Kentucky, there is a Swift Silver mine festival in the county seat of Campton, where locals believe the mine may be located near Swift Creek.