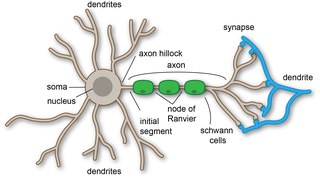

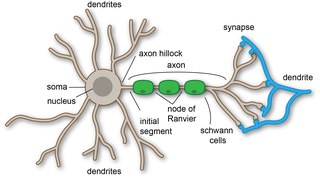

A dendrite or dendron is a branched cytoplasmic process that extends from a nerve cell that propagates the electrochemical stimulation received from other neural cells to the cell body, or soma, of the neuron from which the dendrites project. Electrical stimulation is transmitted onto dendrites by upstream neurons via synapses which are located at various points throughout the dendritic tree.

Hebbian theory is a neuropsychological theory claiming that an increase in synaptic efficacy arises from a presynaptic cell's repeated and persistent stimulation of a postsynaptic cell. It is an attempt to explain synaptic plasticity, the adaptation of brain neurons during the learning process. It was introduced by Donald Hebb in his 1949 book The Organization of Behavior. The theory is also called Hebb's rule, Hebb's postulate, and cell assembly theory. Hebb states it as follows:

Let us assume that the persistence or repetition of a reverberatory activity tends to induce lasting cellular changes that add to its stability. ... When an axon of cell A is near enough to excite a cell B and repeatedly or persistently takes part in firing it, some growth process or metabolic change takes place in one or both cells such that A’s efficiency, as one of the cells firing B, is increased.

In neurophysiology, long-term depression (LTD) is an activity-dependent reduction in the efficacy of neuronal synapses lasting hours or longer following a long patterned stimulus. LTD occurs in many areas of the CNS with varying mechanisms depending upon brain region and developmental progress.

The barrel cortex is a region of the somatosensory cortex that is identifiable in some species of rodents and species of at least two other orders and contains the barrel field. The 'barrels' of the barrel field are regions within cortical layer IV that are visibly darker when stained to reveal the presence of cytochrome c oxidase and are separated from each other by lighter areas called septa. These dark-staining regions are a major target for somatosensory inputs from the thalamus, and each barrel corresponds to a region of the body. Due to this distinctive cellular structure, organisation, and functional significance, the barrel cortex is a useful tool to understand cortical processing and has played an important role in neuroscience. The majority of what is known about corticothalamic processing comes from studying the barrel cortex, and researchers have intensively studied the barrel cortex as a model of neocortical column.

A neural circuit is a population of neurons interconnected by synapses to carry out a specific function when activated. Multiple neural circuits interconnect with one another to form large scale brain networks.

Neural oscillations, or brainwaves, are rhythmic or repetitive patterns of neural activity in the central nervous system. Neural tissue can generate oscillatory activity in many ways, driven either by mechanisms within individual neurons or by interactions between neurons. In individual neurons, oscillations can appear either as oscillations in membrane potential or as rhythmic patterns of action potentials, which then produce oscillatory activation of post-synaptic neurons. At the level of neural ensembles, synchronized activity of large numbers of neurons can give rise to macroscopic oscillations, which can be observed in an electroencephalogram. Oscillatory activity in groups of neurons generally arises from feedback connections between the neurons that result in the synchronization of their firing patterns. The interaction between neurons can give rise to oscillations at a different frequency than the firing frequency of individual neurons. A well-known example of macroscopic neural oscillations is alpha activity.

A neuronal ensemble is a population of nervous system cells involved in a particular neural computation.

Neurotransmission is the process by which signaling molecules called neurotransmitters are released by the axon terminal of a neuron, and bind to and react with the receptors on the dendrites of another neuron a short distance away. A similar process occurs in retrograde neurotransmission, where the dendrites of the postsynaptic neuron release retrograde neurotransmitters that signal through receptors that are located on the axon terminal of the presynaptic neuron, mainly at GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses.

Chandelier cells or chandelier neurons are a subset of GABAergic cortical interneurons. They are described as parvalbumin-containing and fast-spiking to distinguish them from other subtypes of GABAergic neurons, although some studies have suggested that only a subset of chandelier cells test positive for parvalbumin by immunostaining. The name comes from the specific shape of their axon arbors, with the terminals forming distinct arrays called "cartridges". The cartridges are immunoreactive to an isoform of the GABA membrane transporter, GAT-1, and this serves as their identifying feature. GAT-1 is involved in the process of GABA reuptake into nerve terminals, thus helping to terminate its synaptic activity. Chandelier neurons synapse exclusively to the axonal initial segment of pyramidal neurons, near the site where action potential is generated. It is believed that they provide inhibitory input to the pyramidal neurons, but there is data showing that in some circumstances the GABA from chandelier neurons could be excitatory.

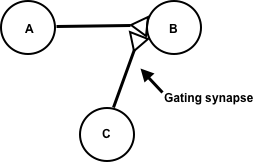

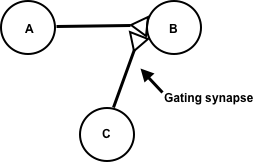

Synaptic gating is the ability of neural circuits to gate inputs by either suppressing or facilitating specific synaptic activity. Selective inhibition of certain synapses has been studied thoroughly, and recent studies have supported the existence of permissively gated synaptic transmission. In general, synaptic gating involves a mechanism of central control over neuronal output. It includes a sort of gatekeeper neuron, which has the ability to influence transmission of information to selected targets independently of the parts of the synapse upon which it exerts its action.

Neural backpropagation is the phenomenon in which, after the action potential of a neuron creates a voltage spike down the axon, another impulse is generated from the soma and propagates towards the apical portions of the dendritic arbor or dendrites. In addition to active backpropagation of the action potential, there is also passive electrotonic spread. While there is ample evidence to prove the existence of backpropagating action potentials, the function of such action potentials and the extent to which they invade the most distal dendrites remain highly controversial.

Coincidence detection is a neuronal process in which a neural circuit encodes information by detecting the occurrence of temporally close but spatially distributed input signals. Coincidence detectors influence neuronal information processing by reducing temporal jitter and spontaneous activity, allowing the creation of variable associations between separate neural events in memory. The study of coincidence detectors has been crucial in neuroscience with regards to understanding the formation of computational maps in the brain.

Subthreshold membrane potential oscillations are membrane oscillations that do not directly trigger an action potential since they do not reach the necessary threshold for firing. However, they may facilitate sensory signal processing.

In neurophysiology, a dendritic spike refers to an action potential generated in the dendrite of a neuron. Dendrites are branched extensions of a neuron. They receive electrical signals emitted from projecting neurons and transfer these signals to the cell body, or soma. Dendritic signaling has traditionally been viewed as a passive mode of electrical signaling. Unlike its axon counterpart which can generate signals through action potentials, dendrites were believed to only have the ability to propagate electrical signals by physical means: changes in conductance, length, cross sectional area, etc. However, the existence of dendritic spikes was proposed and demonstrated by W. Alden Spencer, Eric Kandel, Rodolfo Llinás and coworkers in the 1960s and a large body of evidence now makes it clear that dendrites are active neuronal structures. Dendrites contain voltage-gated ion channels giving them the ability to generate action potentials. Dendritic spikes have been recorded in numerous types of neurons in the brain and are thought to have great implications in neuronal communication, memory, and learning. They are one of the major factors in long-term potentiation.

Ponto-geniculo-occipital waves or PGO waves are distinctive wave forms of propagating activity between three key brain regions: the pons, lateral geniculate nucleus, and occipital lobe; specifically, they are phasic field potentials. These waves can be recorded from any of these three structures during and immediately before REM sleep. The waves begin as electrical pulses from the pons, then move to the lateral geniculate nucleus residing in the thalamus, and end in the primary visual cortex of the occipital lobe. The appearances of these waves are most prominent in the period right before REM sleep, albeit they have been recorded during wakefulness as well. They are theorized to be intricately involved with eye movement of both wake and sleep cycles in many different animals.

Nonsynaptic plasticity is a form of neuroplasticity that involves modification of ion channel function in the axon, dendrites, and cell body that results in specific changes in the integration of excitatory postsynaptic potentials and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials. Nonsynaptic plasticity is a modification of the intrinsic excitability of the neuron. It interacts with synaptic plasticity, but it is considered a separate entity from synaptic plasticity. Intrinsic modification of the electrical properties of neurons plays a role in many aspects of plasticity from homeostatic plasticity to learning and memory itself. Nonsynaptic plasticity affects synaptic integration, subthreshold propagation, spike generation, and other fundamental mechanisms of neurons at the cellular level. These individual neuronal alterations can result in changes in higher brain function, especially learning and memory. However, as an emerging field in neuroscience, much of the knowledge about nonsynaptic plasticity is uncertain and still requires further investigation to better define its role in brain function and behavior.

Cerebellar granule cells form the thick granular layer of the cerebellar cortex and are among the smallest neurons in the brain. Cerebellar granule cells are also the most numerous neurons in the brain: in humans, estimates of their total number average around 50 billion, which means that they constitute about 3/4 of the brain's neurons.

Ephaptic coupling is a form of communication within the nervous system and is distinct from direct communication systems like electrical synapses and chemical synapses. The phrase may refer to the coupling of adjacent (touching) nerve fibers caused by the exchange of ions between the cells, or it may refer to coupling of nerve fibers as a result of local electric fields. In either case ephaptic coupling can influence the synchronization and timing of action potential firing in neurons. Research suggests that myelination may inhibit ephaptic interactions.

Non-spiking neurons are neurons that are located in the central and peripheral nervous systems and function as intermediary relays for sensory-motor neurons. They do not exhibit the characteristic spiking behavior of action potential generating neurons.

An autapse is a chemical or electrical synapse from a neuron onto itself. It can also be described as a synapse formed by the axon of a neuron on its own dendrites, in vivo or in vitro.