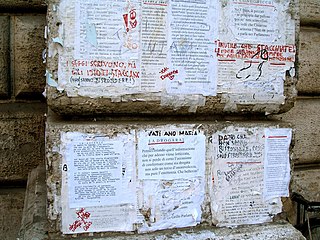

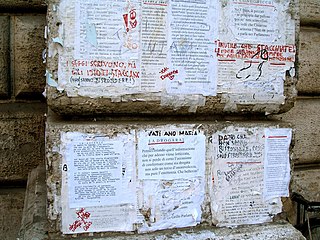

Pasquino or Pasquin is the name used by Romans since the early modern period to describe a battered Hellenistic-style statue perhaps dating to the third century BC, which was unearthed in the Parione district of Rome in the fifteenth century. It is located in a piazza of the same name on the northwest corner of the Palazzo Braschi ; near the site where it was unearthed.

Domenico Fontana was an Italian architect of the late Renaissance, born in today's Ticino. He worked primarily in Italy, at Rome and Naples.

Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi is a fountain in the Piazza Navona in Rome, Italy. It was designed in 1651 by Gian Lorenzo Bernini for Pope Innocent X whose family palace, the Palazzo Pamphili, faced onto the piazza as did the church of Sant'Agnese in Agone of which Innocent was the sponsor.

The Church of St. Louis of the French is a Catholic church near Piazza Navona in Rome. The church is dedicated to the patron saints of France: Virgin Mary, Dionysius the Areopagite and King Louis IX of France.

Acqua Vergine is one of several Roman aqueducts that deliver pure drinking water to Rome. Its name derives from its predecessor Aqua Virgo, which was constructed by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa in 19 BC. Its terminal castellum is located at the Baths of Agrippa, and it served the vicinity of Campus Martius through its various conduits. In an effort to restore fresh water to Rome during the Renaissance, Pope Nicholas V, in 1453, renovated the main channels of the Aqua Virgo and added numerous secondary conduits under Campo Marzio. The original terminus, called a mostra, which means showpiece, was the stately, dignified wall fountain designed by Leon Battista Alberti in Piazza dei Crociferi. Due to several additions and modifications to the end-most points of the conduits during the years that followed, during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, the Acqua Vergine culminated in several magnificent mostre - the Trevi Fountain and the fountains of Piazza del Popolo.

Piazza del Popolo is a large urban square in Rome. The name in modern Italian literally means "People's Square", but historically it derives from the poplars after which the church of Santa Maria del Popolo, in the northeast corner of the piazza, takes its name.

Il Gobbo di Rialto is a marble statue of a hunchback found opposite the Church of San Giacomo di Rialto at the end of the Rialto in Venice. Sculpted by Pietro da Salò in the 16th century, the statue takes the form of a crouching, naked hunchback supporting a small flight of steps.

Babuino is one of the talking statues of Rome, Italy. The fountain is situated in front of the Canova Tadolini Museum, in via del Babuino.

Madama Lucrezia is one of the six "talking statues" of Rome. Pasquinades — irreverent satires poking fun at public figures — were posted beside each of the statues from the 16th century onwards, written as if spoken by the statue, largely in answer to the verses posted at the sculpture called "Pasquino" Madama Lucrezia was the only female "talking statue", and was the subject of competing verses by Pasquino and Marforio.

Marphurius or Marforio is one of the talking statues of Rome. Marforio maintained a friendly rivalry with his most prominent rival, Pasquin. As at the other five "talking statues", pasquinades—irreverent satires poking fun at public figures—were posted beside Marforio in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Il Facchino is one of the talking statues of Rome. Like the other five "talking statues", pasquinades - irreverent satires poking fun at public figures - were posted beside Il Facchino in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Abbot Luigi is one of the talking statues of Rome. Like the other five "talking statues", pasquinades – irreverent satires poking fun at public figures – were posted beside Abate Luigi in the 14th and 15th centuries.

The Pasquino Group is a group of marble sculptures that copy a Hellenistic bronze original, dating to ca. 200–150 BCE. At least fifteen Roman marble copies of this sculpture are known. Many of these marble copies have complex artistic and social histories that illustrate the degree to which improvisatory "restorations" were made to fragments of ancient Roman sculpture during the 16th and 17th centuries, in which contemporary Italian sculptors made original and often arbitrary and destructive additions in an effort to replace lost fragments of the ancient sculptures.

Piazza della Minerva is a piazza in Rome, Italy, near the Pantheon. Its name derives from the existence of a temple built on the site by Pompey dedicated to Minerva Calcidica, whose statue is now in the Vatican Museums.

A pasquinade or pasquil is a form of satire, usually an anonymous brief lampoon in verse or prose, and can also be seen as a form of literary caricature. The genre became popular in early modern Europe, in the 16th century, though the term had been used at least as early as the 4th century, as seen in Augustine's City of God. Pasquinades can take a number of literary forms, including song, epigram, and satire. Compared with other kinds of satire, the pasquinade tends to be less didactic and more aggressive, and is more often critical of specific persons or groups.

Pasquill is the pseudonym adopted by a defender of the Anglican hierarchy in an English political and theological controversy of the 1580s known as the "Marprelate controversy" after "Martin Marprelate", the nom de plume of a Puritan critic of the Anglican establishment. The names of Pasquill and his friend "Marforius", with whom he has a dialogue in the second of the tracts issued in his name, are derived from those of "Pasquino" and "Marforio", the two most famous of the talking statues of Rome, where from the early 16th century on it was customary to paste up anonymous notes or verses commenting on current affairs and scandals.

The Column of the Immaculate Conception is a nineteenth-century monument in central Rome depicting the Blessed Virgin Mary, located in what is called Piazza Mignanelli, towards the south east part of Piazza di Spagna. It was placed aptly in front of the offices of the Palazzo di Propaganda Fide which houses the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples, as well as in front of the Spanish embassy as recognition by the pontiff of the defense that this nation has always made of this dogma of faith.

The Temple of Isis and Serapis was a double temple in Rome dedicated to the Egyptian deities Isis and Serapis on the Campus Martius, directly to the east of the Saepta Julia. The temple to Isis, the Iseum Campense, stood across a plaza from the Serapeum dedicated to Serapis. The remains of the Temple of Serapis now lie under the church of Santo Stefano del Cacco, and the Temple of Isis lay north of it, just east of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. Both temples were made up of a combination of Egyptian and Hellenistic architectural styles. Much of the artwork decorating the temples used motifs evoking Egypt, and they contained several genuinely Egyptian objects, such as couples of obelisks in red or pink granite from Syene.

Palazzo Giustiniani or the Piccolo Colle is a palace on the Via della Dogana Vecchia and Piazza della Rotonda, in Sant'Eustachio, Rome.