Tanka is a genre of classical Japanese poetry and one of the major genres of Japanese literature.

Minamoto no Sanetomo was the third shōgun of the Kamakura shogunate. He was the second son of the Kamakura shogunate founder, Minamoto no Yoritomo. His mother was Hōjō Masako and his older brother was the second Kamakura shogun Minamoto no Yoriie.

Japanese poetry is poetry typical of Japan, or written, spoken, or chanted in the Japanese language, which includes Old Japanese, Early Middle Japanese, Late Middle Japanese, and Modern Japanese, as well as poetry in Japan which was written in the Chinese language or ryūka from the Okinawa Islands: it is possible to make a more accurate distinction between Japanese poetry written in Japan or by Japanese people in other languages versus that written in the Japanese language by speaking of Japanese-language poetry. Much of the literary record of Japanese poetry begins when Japanese poets encountered Chinese poetry during the Tang dynasty. Under the influence of the Chinese poets of this era Japanese began to compose poetry in Chinese kanshi); and, as part of this tradition, poetry in Japan tended to be intimately associated with pictorial painting, partly because of the influence of Chinese arts, and the tradition of the use of ink and brush for both writing and drawing. It took several hundred years to digest the foreign impact and make it an integral part of Japanese culture and to merge this kanshi poetry into a Japanese language literary tradition, and then later to develop the diversity of unique poetic forms of native poetry, such as waka, haikai, and other more Japanese poetic specialties. For example, in the Tale of Genji both kanshi and waka are frequently mentioned. The history of Japanese poetry goes from an early semi-historical/mythological phase, through the early Old Japanese literature inclusions, just before the Nara period, the Nara period itself, the Heian period, the Kamakura period, and so on, up through the poetically important Edo period and modern times; however, the history of poetry often is different from socio-political history.

Ono no Komachi was a Japanese waka poet, one of the Rokkasen — the six best waka poets of the early Heian period. She was renowned for her unusual beauty, and Komachi is today a synonym for feminine beauty in Japan. She also counts among the Thirty-six Poetry Immortals.

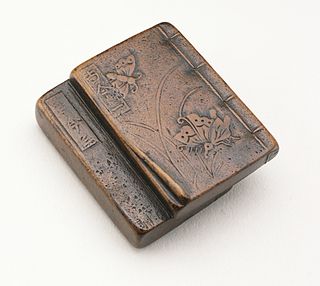

Hyakunin Isshu (百人一首) is a classical Japanese anthology of one hundred Japanese waka by one hundred poets. Hyakunin isshu can be translated to "one hundred people, one poem [each]"; it can also refer to the card game of uta-garuta, which uses a deck composed of cards based on the Hyakunin Isshu.

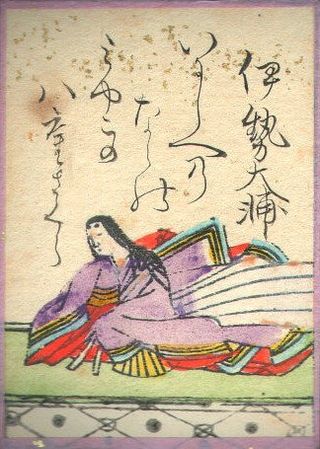

Ise no Taifu (伊勢大輔), also known as Ise no Tayū or Ise no Ōsuke, was a Japanese poet active in the early 11th century.

The lesser cuckoo is a species of cuckoo in the family Cuculidae.

Waka is a type of poetry in classical Japanese literature. Although waka in modern Japanese is written as 和歌, in the past it was also written as 倭歌, and a variant name is yamato-uta (大和歌).

Ōe no Chisato (大江千里) was a Japanese waka poet and Confucian scholar of the late ninth and early tenth centuries. His exact birth and death dates are unknown but he flourished around 889 to 923. He was one of the Chūko Sanjūrokkasen and one of his poems was included in the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu.

Sone no Yoshitada (曾禰好忠) was a Japanese waka poet of the mid-Heian period. His exact dates of birth and death are unknown but he flourished in the second half of the tenth century. He was one of the Thirty-six Immortals of Poetry and one of his poems was included in the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu.

Fujiwara no Kiyosuke was a Japanese waka poet and poetry scholar of the late Heian period.

Asukai Masatsune was a Japanese waka poet of the early Kamakura period. He was also an accomplished kemari player. and one of his poems was included in the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu.

Fujiwara no Sadayori was a Japanese waka poet of the mid-Heian period. One of his poems was included in the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu. He produced a private collection.

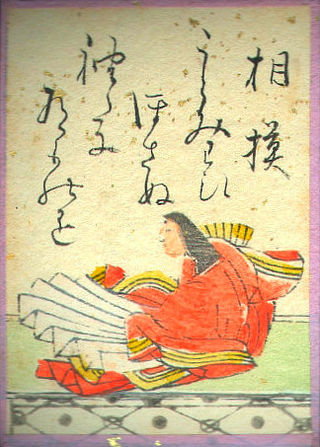

Sagami, also known as Oto-jijū (乙侍従), was a Japanese waka poet of the mid-Heian period. One of her poems was included in the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu. She produced a private collection, the Sagami-shū.

Fujiwara no Yoshitaka was a Japanese waka poet of the mid-Heian period. One of his poems was included in the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu. He produced a private waka collection, the Yoshitaka-shū.

Fujiwara no Sanekata was a Japanese waka poet of the mid-Heian period. One of his poems was included in the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu. He left a private waka collection, the Sanekata-shū.

Gyōson, also known as the Abbot of Byōdō-in, was a Japanese Tendai monk and waka poet of the late-Heian period. He became chief prelate of the Enryaku-ji temple in Kyoto, and one of his poems was included in the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu. Almost fifty of his poems were included in imperial anthologies, and he produced a private collection of poetry.

Shun'e, also known as Tayū no Kimi (大夫公), was a Japanese waka poet of the late-Heian period. One of his poems was included in the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu. He produced a private collection, the Rin'yō Wakashū, and was listed as one of the Late Classical Thirty-Six Immortals of Poetry.