Related Research Articles

Alexios I Komnenos, Latinized as Alexius I Comnenus, was Byzantine emperor from 1081 to 1118. Inheriting a collapsing empire and faced with constant warfare during his reign, Alexios was able to curb the Byzantine decline and begin the military, financial, and territorial recovery known as the Komnenian restoration. His appeals to Western Europe for help against the Seljuk Turks were the catalyst that sparked the First Crusade. Although he was not the first emperor of the Komnenian dynasty, it was during his reign that the Komnenos family came to full power and initiated a hereditary succession to the throne.

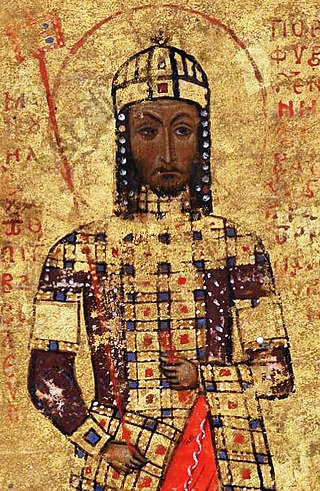

Manuel I Komnenos, Latinized as Comnenus, also called Porphyrogenitus, was a Byzantine emperor of the 12th century who reigned over a crucial turning point in the history of Byzantium and the Mediterranean. His reign saw the last flowering of the Komnenian restoration, during which the Byzantine Empire experienced a resurgence of military and economic power and enjoyed a cultural revival.

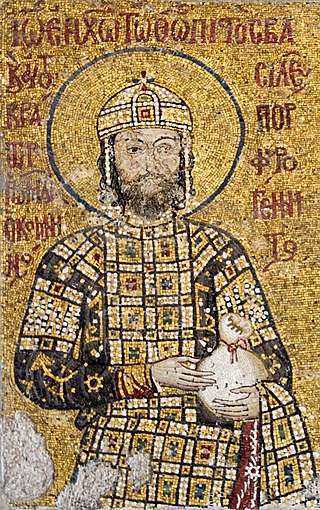

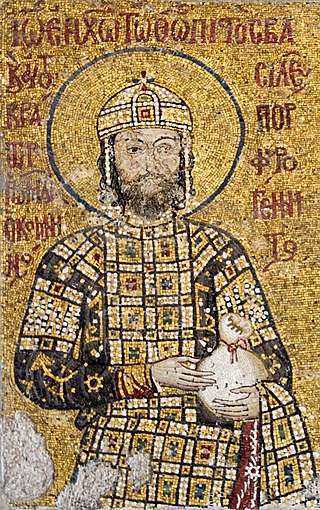

John II Komnenos or Comnenus was Byzantine emperor from 1118 to 1143. Also known as "John the Beautiful" or "John the Good", he was the eldest son of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and Irene Doukaina and the second emperor to rule during the Komnenian restoration of the Byzantine Empire. As he was born to a reigning emperor, he had the status of a porphyrogennetos. John was a pious and dedicated monarch who was determined to undo the damage his empire had suffered following the Battle of Manzikert, half a century earlier.

Anna Komnene, commonly Latinized as Anna Comnena, was a Byzantine Greek princess and historian. She is the author of the Alexiad, an account of the reign of her father, Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos. Her work constitutes the most important primary source of Byzantine history of the late 11th and early 12th centuries, as well as of the early Crusades. Although she is best known as the author of the Alexiad, Anna played an important part in the politics of the time and attempted to depose her brother, John II Komnenos, as emperor in favour of her husband, Nikephoros.

Hugh, called the Great was the first count of Vermandois from the House of Capet. He is known primarily for being one of the leaders of the First Crusade. His nickname Magnus is probably a bad translation into medieval Latin of an Old French nickname, le Maisné, meaning "the younger", referring to Hugh as younger brother of King Philip I of France.

Robert II, Count of Flanders was Count of Flanders from 1093 to 1111. He became known as Robert of Jerusalem or Robert the Crusader after his exploits in the First Crusade.

The Battle of Dorylaeum took place during the First Crusade on 1 July 1097 between the crusader forces and the Seljuk Turks, near the city of Dorylaeum in Anatolia. Though the Turkish forces of Kilij Arslan nearly destroyed the Crusader contingent of Bohemond, other Crusaders arrived just in time to reverse the course of the battle.

The Alexiad is a medieval historical and biographical text written around the year 1148, by the Byzantine princess Anna Komnene, daughter of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. It was written in a form of artificial Attic Greek. Anna described the political and military history of the Byzantine Empire during the reign of her father, thus providing a significant account on the Byzantium of the High Middle Ages. Among other topics, the Alexiad documents the Byzantine Empire's interaction with the Crusades and highlights the conflicting perceptions of the East and West in the early 12th century. It does not mention the schism of 1054 – a topic which is very common in contemporary writing. It documents firsthand the decline of Byzantine cultural influence in eastern and western Europe, particularly in the West's increasing involvement in its geographic sphere. The Alexiad was paraphrased in vernacular medieval Greek in mid-14th century to increase its readability, which testifies to the work's lasting interest.

The siege of Nicaea was the first major battle of the First Crusade, taking place from 14 May to 19 June 1097. The city was under the control of the Seljuk Turks who opted to surrender to the Byzantines in fear of the crusaders breaking into the city. The siege was followed by the Battle of Dorylaeum and the Siege of Antioch, all taking place in modern Turkey.

The rhomphaia was a close-combat bladed weapon used by the Thracians as early as 350-400 BC. Rhomphaias were weapons with a straight or slightly curved single-edged blade. Although the rhomphaia was similar to the falx, most archaeological evidence suggests that rhomphaias were forged with straight or slightly curved blades, presumably to enable their use as both a thrusting and slashing weapon. The blade was constructed of iron and used a triangular cross section to accommodate the single cutting edge with a tang of rectangular cross section. Length varied, but a typical rhomphaia would have a blade of approximately 60–80 cm (24–31 in) and a tang of approximately 50 cm (20 in). From the length of the tang, it can be presumed that, when attached to the hilt, this portion of the weapon would be of similar length to the blade.

The Byzantine army of the Komnenian era or Komnenian army was a force established by Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos during the late 11th/early 12th century. It was further developed during the 12th century by his successors John II Komnenos and Manuel I Komnenos. From necessity, following extensive territorial loss and a near disastrous defeat by the Normans of southern Italy at Dyrrachion in 1081, Alexios constructed a new army from the ground up. This new army was significantly different from previous forms of the Byzantine army, especially in the methods used for the recruitment and maintenance of soldiers. The army was characterised by an increased reliance on the military capabilities of the immediate imperial household, the relatives of the ruling dynasty and the provincial Byzantine aristocracy. Another distinctive element of the new army was an expansion of the employment of foreign mercenary troops and their organisation into more permanent units. However, continuity in equipment, unit organisation, tactics and strategy from earlier times is evident. The Komnenian army was instrumental in creating the territorial integrity and stability that allowed the Komnenian restoration of the Byzantine Empire. It was deployed in the Balkans, Italy, Hungary, Russia, Anatolia, Syria, the Holy Land and Egypt.

The Byzantine–Seljuk wars were a series of conflicts in the Middle Ages between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Empire. They shifted the balance of power in Asia Minor and Syria from the Byzantines to the Seljuk dynasty. Riding from the steppes of Central Asia, the Seljuks replicated tactics practiced by the Huns hundreds of years earlier against a similar Roman opponent but now combining it with new-found Islamic zeal. In many ways, the Seljuk resumed the conquests of the Muslims in the Byzantine–Arab Wars initiated by the Rashidun, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates in the Levant, North Africa and Asia Minor.

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors of the Komnenos dynasty for a period of 104 years, from 1081 to about 1185. The Komnenian period comprises the reigns of five emperors, Alexios I, John II, Manuel I, Alexios II and Andronikos I. It was a period of sustained, though ultimately incomplete, restoration of the military, territorial, economic and political position of the Byzantine Empire.

Nikephoros Bryennios the Elder, Latinized as Nicephorus Bryennius, was a Byzantine Greek general who tried to establish himself as Emperor in the late eleventh century. His contemporaries considered him the best tactician in the empire.

John Axouch or Axouchos (Greek: Ἰωάννης Ἀξούχ or Ἀξοῦχος, romanized: Iōánnēs Axoûchos,, also transliterated as Axuch, was the commander-in-chief of the Byzantine army during the reign of Emperor John II Komnenos, and during the early part of the reign of his son Manuel I Komnenos. He may also have served as the de facto chief of the civil administration of the Byzantine Empire.

The Byzantine–Norman wars were a series of military conflicts between the Normans and the Byzantine Empire fought from c. 1040 to 1186 involving the Norman-led Kingdom of Sicily in the west, and the Principality of Antioch in the Levant. The last of the Norman invasions, though having incurred disaster upon the Romans by sacking Thessalonica in 1185, was eventually driven out and vanquished by 1186.

The Battle of Philomelion of 1116 consisted of a series of clashes over a number of days between a Byzantine expeditionary army under Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and the forces of the Sultanate of Rûm under Sultan Malik Shah; it occurred in the course of the Byzantine–Seljuk wars. The Seljuk forces attacked the Byzantine army a number of times to no effect; having suffered losses to his army in the course of these attacks, Malik Shah sued for peace.

Manuel Boutoumites or Butumites was a leading Byzantine general and diplomat during the reign of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, and one of the emperor's most trusted aides. He was instrumental in the Byzantine recovery of Nicaea from the Seljuk Turks, in the reconquest of Cilicia, and acted as the emperor's envoy in several missions to Crusader princes.

The following is an overview of the armies of First Crusade, including the armies of the European noblemen of the "Princes' Crusade", the Byzantine army, a number of Independent crusaders as well as the People's Crusade and the subsequent Crusade of 1101 and other European campaigns prior to the Second Crusade beginning in 1147.

The Battle of Larissa was a military engagement between the armies of the Byzantine Empire and the Italo-Norman County of Apulia and Calabria. On 3 November 1082, the Normans besieged the city of Larissa. In July of the following year, Byzantine reinforcements attacked the blockading force, harassing it with mounted archers and spreading discord among its ranks through diplomatic techniques. The demoralized Normans were forced to break off the siege.

References

Primary:

- Choniates, Niketas (1984). O City of Byzantium: Annals of Niketas Choniates. transl. by H. Magoulias. Detroit. ISBN 0-8143-1764-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Komnene (Comnena), Anna; Edgar Robert Ashton Sewter (1969). "XLVIII-The First Crusade". The Alexiad of Anna Comnena translated by Edgar Robert Ashton Sewter. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044215-4.

Secondary:

- Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, Vol. 1: The First Crusade. Cambridge, 1952.

- Skoulatos, Basile (1980). Les personnages byzantins de l'Alexiade: Analyse prosopographique et synthèse[The Byzantine Personalities of the Alexiad: Prosopographical Analysis and Synthesis] (in French). Louvain-la-Neuve: Nauwelaerts.

- Albert of Aix, Historia Hierosolymitana.

- Gesta Francorum et aliorum Hierosolimitanorum (anonymous)

- Guibert of Nogent, Dei gesta per Francos .

- Peter Tudebode, Historia de Hierosolymitano itinere.

- Raymond of Aguilers, Historia Francorum qui ceperunt Iherusalem .

- Charles M. Brand, "The Turkish Element in Byzantium, Eleventh-Twelfth Centuries", Dumbarton Oaks Papers43:1-25 (1989) at JSTOR

- Magdalino, Paul (2002). The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 1143–1180. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52653-1.