Related Research Articles

Alexandrine is a name used for several distinct types of verse line with related metrical structures, most of which are ultimately derived from the classical French alexandrine. The line's name derives from its use in the Medieval French Roman d'Alexandre of 1170, although it had already been used several decades earlier in Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne. The foundation of most alexandrines consists of two hemistichs (half-lines) of six syllables each, separated by a caesura :

o o o o o o | o o o o o o o=any syllable; |=caesura

In poetry, a hendecasyllable is a line of eleven syllables. The term may refer to several different poetic meters, the older of which are quantitative and used chiefly in classical poetry, and the newer of which are syllabic or accentual-syllabic and used in medieval and modern poetry.

In poetry, metre or meter is the basic rhythmic structure of a verse or lines in verse. Many traditional verse forms prescribe a specific verse metre, or a certain set of metres alternating in a particular order. The study and the actual use of metres and forms of versification are both known as prosody.

Syllabic verse is a poetic form having a fixed or constrained number of syllables per line, while stress, quantity, or tone play a distinctly secondary role—or no role at all—in the verse structure. It is common in languages that are syllable-timed, such as French or Finnish, as opposed to stress-timed languages such as English, in which accentual verse and accentual-syllabic verse are more common.

A rubāʿī or chahārgāna is a poem or a verse of a poem in Persian poetry in the form of a quatrain, consisting of four lines.

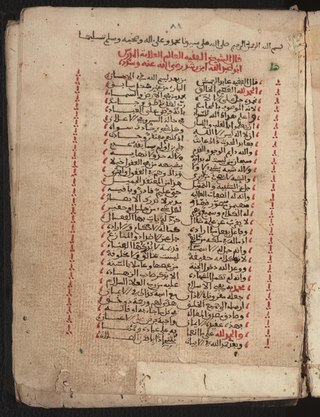

Arabic poetry is one of the earliest forms of Arabic literature. Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry contains the bulk of the oldest poetic material in Arabic, but Old Arabic inscriptions reveal the art of poetry existed in Arabic writing in material as early as the 1st century BCE, with oral poetry likely being much older still.

Muwashshah is the name for both an Arabic poetic form and a musical genre. The poetic form consists of a multi-lined strophic verse poem written in classical Arabic, usually consisting of five stanzas, alternating with a refrain with a running rhyme. It was customary to open with one or two lines which matched the second part of the poem in rhyme and meter; in North Africa poets ignore the strict rules of Arabic meter while the poets in the East follow them. The musical genre of the same name uses muwaššaḥ texts as lyrics, still in classical Arabic. This tradition can take two forms: the waṣla of the Mashriq and the Arab Andalusi nubah of the western part of the Arab world.

Political verse, also known as decapentasyllabic verse, is a common metric form in Medieval and Modern Greek poetry. It is an iambic verse of fifteen syllables and has been the main meter of traditional popular and folk poetry since the Byzantine period.

Hazaj meter is a quantitative verse meter frequently found in the epic poetry of the Middle East and western Asia. A musical rhythm[a] of the same name[b] is based on the literary meter.

Basīṭ, or al-basīṭ (البسيط), is a metre used in classical Arabic poetry. The word literally means "extended" or "spread out" in Arabic. Along with the ṭawīl, kāmil, and wāfir, it is one of the four most common metres used in pre-Islamic and classical Arabic poetry.

A bayt is a metrical unit of Arabic, Azerbaijani, Ottoman, Persian, Punjabi, Sindhi and Urdu poetry.

ʿArūḍ or ʿilm al-ʿarūḍ is the study of poetic meters, which identifies the meter of a poem and determines whether the meter is sound or broken in lines of the poem. It is often called the Science of Poetry. Its laws were laid down by Al-Khalīl ibn Aḥmad al-Farāhīdī, an early Arab lexicographer and philologist. In his book Al-ʿArḍ, which is no longer extant, he described 15 types of meter. Later Al-Akhfash al-Akbar described a 16th meter, the mustadārik.

The French alexandrine is a syllabic poetic metre of 12 syllables with a medial caesura dividing the line into two hemistichs (half-lines) of six syllables each. It was the dominant long line of French poetry from the 17th through the 19th century, and influenced many other European literatures which developed alexandrines of their own.

Rajaz is a metre used in classical Arabic poetry. A poem composed in this metre is an urjūza. The metre accounts for about 3% of surviving ancient and classical Arabic verse.

Wāfir is a meter used in classical Arabic poetry. It is among the five most popular metres of classical Arabic poetry, accounting for 80-90% of lines and poems in the ancient and classical Arabic corpus.

Persian metres are the patterns of long and short syllables, 10 to 16 syllables long, used in Persian poetry.

Kāmil is the second commonest metre used in pre-Islamic and classical Arabic poetry. The usual form of the metre is as follows :

The Madīd metre is one of the metres used in classical Arabic poetry. The theoretical pattern of the metre is as follows, where u = a short syllable, – a long syllable, and x = anceps :

Alā yā ayyoha-s-sāqī is a ghazal by the 14th-century poet Hafez of Shiraz. It is the opening poem in the collection of Hafez's 530 poems.

A metron, , plural metra, is a repeating section, 3 to 6 syllables long, of a poetic metre. The word is particularly used in reference to ancient Greek. According to a definition by Paul Maas, usually a metron consists of two long elements and up to two other elements which can be short, anceps or biceps.

References

- ↑ Classical Arabic Literature: A Library of Arabic Literature Anthology, trans. by Geert Jan van Gelder (New York: New York University Press, 2013), p. xxiii.

- ↑ Charles Greville Tuetey (trans.), Classical Arabic Poetry: 162 Poems from Imrulkais to Maʿarri (London: KPI, 1985), pp. 8-9.

- 1 2 W. Stoetzer, 'Ṭawīl', in Encyclopaedia of Islam, ed. P. Bearman and others, 2nd edn (Leiden: Brill, 1960-2007), doi : 10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_7455, ISBN 9789004161214.

- ↑ Muhammad al-Sharkawi, The Ecology of Arabic: A Study of Arabicization, Studies in Semitic Languages and Linguistics, 60 (Leiden: Brill, 2010), pp. 82, 83 n. 17.

- ↑ Arabic Poems: A Bilingual Edition, ed. by Marlé Hammond, Everyman's Library (New York: Knopf, 2014), p. 12.

- ↑ Classical Arabic Literature: A Library of Arabic Literature Anthology, trans. by Geert Jan van Gelder (New York: New York University Press, 2013), p. xxiii.

- ↑ The Moallakát: Or Seven Arabian Poems, which Were Suspended on the Temple at Mecca; with a Translation, a Preliminary Discourse, and Notes Critical, Philological, Explanatory. By William Jones, Esq. J. Nichols. 1782.