Little Turtle was a Sagamore (chief) of the Miami people, who became one of the most famous Native American military leaders. Historian Wiley Sword calls him "perhaps the most capable Indian leader then in the Northwest Territory," although he later signed several treaties ceding land, which caused him to lose his leader status during the battles which became a prelude to the War of 1812. In the 1790s, Mihšihkinaahkwa led a confederation of native warriors to several major victories against U.S. forces in the Northwest Indian Wars, sometimes called "Little Turtle's War", particularly St. Clair's defeat in 1791, wherein the confederation defeated General Arthur St. Clair, who lost 900 men in the most decisive loss by the U.S. Army against Native American forces.

The Battle of Tippecanoe was fought on November 7, 1811, in Battle Ground, Indiana between American forces led by Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory and Indian forces associated with Shawnee leader Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa, leaders of a confederacy of various tribes who opposed European-American settlement of the American frontier. As tensions and violence increased, Governor Harrison marched with an army of about 1,000 men to attack the confederacy's headquarters at Prophetstown, near the confluence of the Tippecanoe River and the Wabash River.

The Miami are a Native American nation originally speaking one of the Algonquian languages. Among the peoples known as the Great Lakes tribes, it occupied territory that is now identified as North-central Indiana, southwest Michigan, and western Ohio. By 1846, most of the Miami had been forcefully displaced to Indian Territory. The Miami Tribe of Oklahoma is the federally recognized tribe of Miami Indians in the United States. The Miami Nation of Indiana, a nonprofit organization of descendants of Miamis who were exempted from removal, has unsuccessfully sought separate recognition.

Battle Ground is a town in Tippecanoe Township, Tippecanoe County in the U.S. state of Indiana. The population was 1,334 at the 2010 census. It is near the site of the Battle of Tippecanoe.

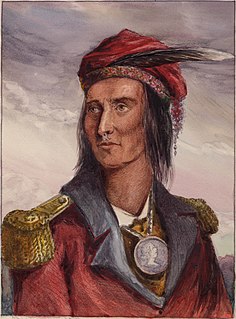

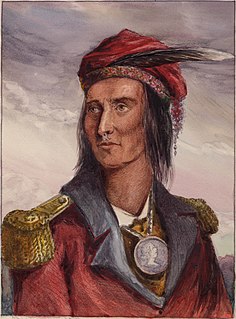

Tecumseh was a Shawnee leader who became the primary leader of a large Native American confederacy in the early 19th century.

Tecumseh's War or Tecumseh's Rebellion was a conflict between the United States and Tecumseh's Confederacy, led by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh in the Indiana Territory. Although the war is often considered to have climaxed with William Henry Harrison's victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, Tecumseh's War essentially continued into the War of 1812 and is frequently considered a part of that larger struggle. The war lasted for two more years, until 1813, when Tecumseh and his second-in-command, Roundhead, died fighting Harrison's Army of the Northwest at the Battle of the Thames in Upper Canada, near present-day Chatham, Ontario, and his confederacy disintegrated. Tecumseh's War is viewed by some academic historians as the final conflict of a longer-term military struggle for control of the Great Lakes region of North America, encompassing a number of wars over several generations, referred to as the Sixty Years' War.

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking ethnic group indigenous to North America. In colonial times they were a semi-migratory Native American nation, primarily inhabiting areas of the Ohio Valley, extending from what became Ohio and Kentucky eastward to West Virginia, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Western Maryland; south to Alabama and South Carolina; and westward to Indiana, and Illinois.

Tenskwatawa was a Native American religious and political leader of the Shawnee, known as the Prophet or the Shawnee Prophet. He was a younger brother of Tecumseh, a leader of the Shawnee. In his early years Tenskwatawa was given the name Lalawithika by the Red Sticks, a faction of the Muscogee.

Buckongahelas was a regionally and nationally renowned Lenape chief, councilor and warrior. He was active from the days of the French and Indian War through the Northwest Indian Wars, after the United States achieved independence and settlers encroached on territory beyond the Appalachian Mountains and Ohio River. He became involved in the Western Confederacy of mostly Algonquian-speaking peoples, who were seeking to repel American settlers. The chief led his Lenape band from present-day Delaware westward, eventually to the White River area of present-day Muncie, Indiana. One of the most powerful war chiefs on the White River, Buckongahelas was respected by the Americans as a chief, although he did not have the position to do political negotiations.

Prophetstown State Park commemorates a Native American village founded in 1808 by Shawnee leaders Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa north of present-day Lafayette, Indiana, which grew into a large, multi-tribal community. The park also features the open-air Museum at Prophetstown, with living history exhibits including a Shawnee village and a 1920s-era farmstead. Battle Ground, Indiana, is a village about a mile east of the site of the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, a crucial battle in the Tecumseh's War which ultimately led to that initial village's demise. Indiana’s newest state park was established in 2004.

The Treaty of Fort Wayne, sometimes called the Ten O'clock Line Treaty or the Twelve Mile Line Treaty, is an 1809 treaty that obtained 3,000,000 acres of Native American land for the white settlers of Illinois and Indiana. The negotiations primarily involved the Delaware tribe but included other tribes as well. However, the negotiations excluded the Shawnee, who were minor inhabitants of the area and had previously been asked to leave by Miami War Chief Little Turtle. Territorial Governor William Henry Harrison negotiated the treaty with the tribes. The treaty led to a war with the United States begun by Shawnee leader Tecumseh and other dissenting tribesmen in what came to be called "Tecumseh's War".

During the War of 1812, the Illinois Territory was the scene of fighting between Native Americans and United States soldiers and settlers. The Illinois Territory at that time included the areas of modern Illinois, Wisconsin and parts of Minnesota and Michigan.

Shawnee Methodist Mission was established by missionaries in 1830 in Turner, Kansas to minister to the Shawnee tribe of Native Americans who had been removed to Kansas. In 1839 the mission relocated to Fairway, where it built a brick building referred to by names varying from Shawnee Indian Methodist Manual Labor School. It was one of the first such missions established in the territory acquired by the United States in the Louisiana Purchase. Designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1968, the Shawnee Methodist Mission is operated today as a museum. The site is administered by the Kansas Historical Society as the Shawnee Indian Mission State Historic Site.

Winamac was the name of a number of Potawatomi leaders and warriors beginning in the late 17th century. The name derives from a man named Wilamet, a Native American from an eastern tribe who in 1681 was appointed to serve as a liaison between New France and the natives of the Lake Michigan region. Wilamet was adopted by the Potawatomis, and his name, which meant "Catfish" in his native Eastern Algonquian language, was soon transformed into "Winamac", which means the same thing in the Potawatomi language. The Potawatomi version of the name has been spelled in a variety of ways, including Winnemac, Winamek, and Winnemeg.

The Western Confederacy, or Western Indian Confederacy, was a loose confederacy of Native Americans in the Great Lakes region of the United States created following the American Revolutionary War. Formally, the confederacy referred to itself as the United Indian Nations, at their Confederate Council. It is also known as the Miami Confederacy, since many contemporaneous federal officials overestimated the influence and numerical strength of the Miami tribes based on the size of their principle city, Kekionga. The confederacy, which had its roots in pan-tribal movements dating to the 1740s, formed in an attempt to resist the expansion of the United States and the encroachment of American settlers into the Northwest Territory after Great Britain ceded the region to the U.S. in the 1783 Treaty of Paris. This resulted in the Northwest Indian War (1785–1795), in which the Confederacy won significant victories over the United States, but concluded with an U.S. victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The Confederacy became fractured and agreed to peace with the United States, but the pan-tribal resistance was later rekindled by Tenskwatawa and his brother, Tecumseh.

During the War of 1812, Indiana Territory was home to several conflicts between the United States territorial government and partisan Native American forces backed by the British in Canada. The Battle of Tippecanoe, which had occurred just months before the war began, was one of the catalysts that caused the war. The war in the territory is often considered a continuation of Tecumseh's War, and the final struggle of the Sixty Years' War.

Tsali, originally of Coosawattee Town (Kusawatiyi), was a noted leader of the Cherokee during two different periods of the history of the tribe. As a young man, he followed the Chickamauga Cherokee war chief, Dragging Canoe, from the time the latter migrated southwest during the Cherokee–American wars. In 1812 he became known as a prophet, urging the Cherokee to ally with the Shawnee Tecumseh in war against the Americans.

Scattamek was a Lenape living in the Ohio Country during the 18th century. He was a religious leader later termed a prophet who continued and built on the teachings of Neolin. Their teachings influenced many of the surrounding tribes, including the Shawnee, the Miami, and Wea. Scattamek is known to have been teaching during the 1770s. The teachings were largely based on earlier traditions, but their teachings focused on the need to return to the tribe's ancestral ways, giving up European dress, liquor, and firearms. They blamed their misfortunes on the gods anger with their adoption of European customs. Scattamek had particular influence on Tenskwatawa, who led a nativist revival during the early 19th century that catalyzed tribal support for Tecumseh's War during the 1810s.

The following units of the U.S. Army and state militia forces under Indiana Governor William Henry Harrison, fought against the Native American warriors of Tecumseh's Confederacy, led by Chief Tecumseh's brother, Tenskwatawa "The Prophet" at the battle of Tippecanoe on November 7, 1811.