Hatshepsut was the Great Royal Wife of Pharaoh Thutmose II and the fifth Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, ruling first as regent, then as queen regnant from c. 1479 BC until c. 1458 BC. She was Egypt's second confirmed queen regnant, the first being Sobekneferu/Nefrusobek in the Twelfth Dynasty.

The 1470s BC was a decade lasting from January 1, 1479 BC to December 31, 1470 BC.

Thutmose II was the fourth Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, and his reign is generally dated from 1493 to 1479 BC. Little is known about him and he is overshadowed by his father Thutmose I, half-sister and wife Hatshepsut, and son Thutmose III. He died around the age of 30 and his body was found in the Deir el-Bahri Cache above the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut.

Amenhotep I or Amenophis I, was the second Pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. His reign is generally dated from 1526 to 1506 BC.

Ineni was an ancient Egyptian architect and government official of the 18th Dynasty, responsible for major construction projects under the pharaohs Amenhotep I, Thutmose I, Thutmose II and the joint reigns of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. He had many titles, including Superintendent of the Granaries, Superintendent of the Royal Buildings, Superintendent of the Workmen in the Karnak Treasuries, etc.

Senenmut was an 18th Dynasty ancient Egyptian architect and government official. His name translates literally as "brother of mother."

Deir el-Bahari or Dayr al-Bahri is a complex of mortuary temples and tombs located on the west bank of the Nile, opposite the city of Luxor, Egypt. This is a part of the Theban Necropolis.

Mentuhotep II, also known under his prenomen Nebhepetre, was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, the sixth ruler of the Eleventh Dynasty. He is credited with reuniting Egypt, thus ending the turbulent First Intermediate Period and becoming the first pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom. He reigned for 51 years, according to the Turin King List. Mentuhotep II succeeded his father Intef III on the throne and was in turn succeeded by his son Mentuhotep III.

Mortuary temples were temples that were erected adjacent to, or in the vicinity of, royal tombs in Ancient Egypt. The temples were designed to commemorate the reign of the Pharaoh under whom they were constructed, as well as for use by the king's cult after death. Some refer to these temples as a cenotaph. These temples were also used to make sacrifices of food and animals.

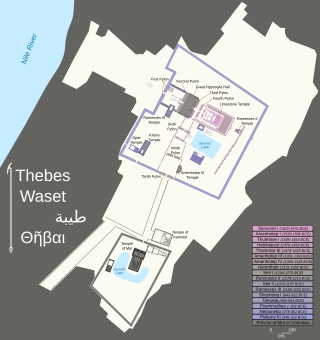

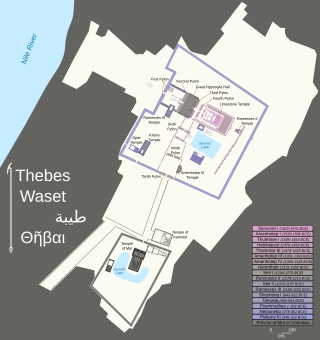

The Precinct of Amun-Re, located near Luxor, Egypt, is one of the four main temple enclosures that make up the immense Karnak Temple Complex. The precinct is by far the largest of these and the only one that is open to the general public. The temple complex is dedicated to the principal god of the Theban Triad, Amun, in the form of Amun-Re.

Herbert Eustis Winlock was an American Egyptologist and archaeologist, employed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art for his entire career. Between 1906 and 1931 he took part in excavations at El-Lisht, Kharga Oasis and around Luxor, before serving as director of the Metropolitan Museum from 1932 to 1939.

Hapuseneb was the High Priest of Amun during the reign of Hatshepsut.

The mortuary temple of Hatshepsut is a mortuary temple built during the reign of Pharaoh Hatshepsut of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Located opposite the city of Luxor, it is considered to be a masterpiece of ancient architecture. Its three massive terraces rise above the desert floor and into the cliffs of Deir el-Bahari. Her tomb, KV20, lies inside the same massif capped by El Qurn, a pyramid for her mortuary complex. At the edge of the desert, 1 km (0.62 mi) east, connected to the complex by a causeway lies the accompanying valley temple. Across the river Nile, the whole structure points towards the monumental Eighth Pylon, Hatshepsut's most recognizable addition to the Temple of Karnak and the site from which the procession of the Beautiful Festival of the Valley departed. The temple's twin functions are identified by its axes: its main east-west axis served to receive the barque of Amun-Re at the climax of the festival, while its north-south axis represented the life cycle of the pharaoh from coronation to rebirth.

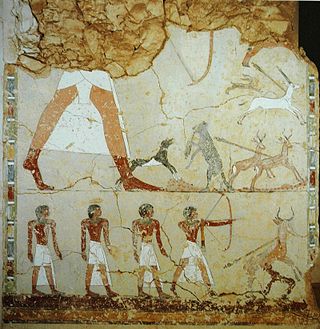

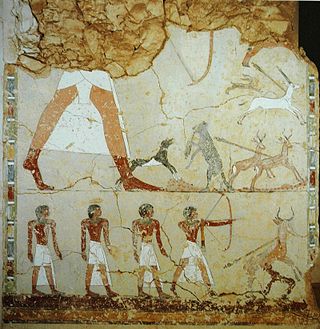

Bas-relief carvings in the ancient Egyptian temple of Deir el-Bahari depict events in the life of the pharaoh or monarch Hatshepsut of the Eighteenth Dynasty. They show the Egyptian gods, in particular Amun, presiding over her creation, and describe the ceremonies of her coronation. Their purpose was to confirm the legitimacy of her status as a woman pharaoh. Later rulers attempted to erase the inscriptions.

The Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt is classified as the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, the era in which ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power. The Eighteenth Dynasty spanned the period from 1550/1549 to 1292 BC. This dynasty is also known as the Thutmoside Dynasty) for the four pharaohs named Thutmose.

Nathalie Beaux-Grimal is a French Egyptologist, a research associate at the Collège de France and the French Institute of Oriental Archaeology in Cairo (IFAO).

The Research Centre in Cairo, Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology University of Warsaw, is the only Polish scientific research institution in Africa and the Middle East, where it has operated since 1959 in Cairo. The mission of the Research Centre is to develop and expand Polish research in the region, particularly in the Nile Valley. It is operated by the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, an independent research institute of the University of Warsaw. The PCMA Cairo Research Centre is located in two buildings situated in close proximity to one another in the Cairo Heliopolis district — in antiquity the centre of a religious cult and the location of the Egypt's reputedly largest temple.

North Asasif – is a part of the Theban Necropolis located on the bottom and sides of the valley, along the processional ways leading to the royal temples in Deir el-Bahari: temples of Mentuhotep II, Hatshepsut, and Thutmose III. It encompasses private tombs dating from the Middle Kingdom to the Ptolemaic period. Evidence has been found of strong ties between Asasif and Deir el-Bahari through the ages.

Jadwiga Lipińska née Freyer was a Polish Egyptologist.

Andrzej Stefan Niwiński is a Polish archaeologist, specializing in the field of religious iconography and mythological studies of the XXI–XXII Dynasty. Especially known as a specialist in the studies of coffins from XXI dynasty, and his search for tomb of Herihor.