A bestiary is a compendium of beasts. Originating in the ancient world, bestiaries were made popular in the Middle Ages in illustrated volumes that described various animals and even rocks. The natural history and illustration of each beast was usually accompanied by a moral lesson. This reflected the belief that the world itself was the Word of God and that every living thing had its own special meaning. For example, the pelican, which was believed to tear open its breast to bring its young to life with its own blood, was a living representation of Jesus. Thus the bestiary is also a reference to the symbolic language of animals in Western Christian art and literature.

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal.

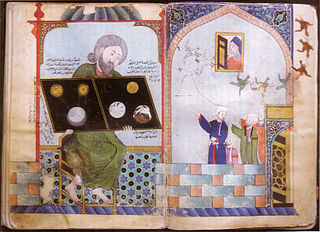

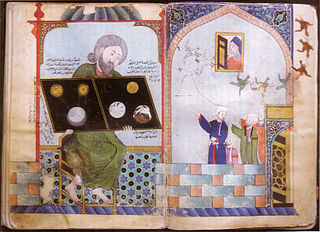

In the Middle Ages, the medicine of Western Europe was composed of a mixture of existing ideas from antiquity. In the Early Middle Ages, following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, standard medical knowledge was based chiefly upon surviving Greek and Roman texts, preserved in monasteries and elsewhere. Medieval medicine is widely misunderstood, thought of as a uniform attitude composed of placing hopes in the church and God to heal all sicknesses, while sickness itself exists as a product of destiny, sin, and astral influences as physical causes. On the other hand, medieval medicine, especially in the second half of the medieval period, became a formal body of theoretical knowledge and was institutionalized in the universities. Medieval medicine attributed illnesses, and disease, not to sinful behaviour, but to natural causes, and sin was connected to illness only in a more general sense of the view that disease manifested in humanity as a result of its fallen state from God. Medieval medicine also recognized that illnesses spread from person to person, that certain lifestyles may cause ill health, and some people have a greater predisposition towards bad health than others.

John of Seville was one of the main translators from Arabic into Castilian in partnership with Dominicus Gundissalinus during the early days of the Toledo School of Translators. John of Seville translated a litany of Arabic astrological works in addition to being credited with the production of several original works in Latin.

Cosmas Indicopleustes was a merchant and later hermit from Alexandria in Egypt. He was a 6th-century traveller who made several voyages to India during the reign of emperor Justinian. His work Christian Topography contained some of the earliest and most famous world maps. Cosmas was a pupil of the East Syriac Patriarch Aba I and was himself a follower of the Church of the East.

Boetius de Dacia, OP was a 13th-century Danish philosopher.

Ancient Greek astronomy is the astronomy written in the Greek language during classical antiquity. Greek astronomy is understood to include the Ancient Greek, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman, and late antique eras. It is not limited geographically to Greece or to ethnic Greeks, as the Greek language had become the language of scholarship throughout the Hellenistic world following the conquests of Alexander. This phase of Greek astronomy is also known as Hellenistic astronomy, while the pre-Hellenistic phase is known as Classical Greek astronomy. During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, many of the Greek and non-Greek astronomers working in the Greek tradition studied at the Museum and the Library of Alexandria in Ptolemaic Egypt.

Lawrence Irvin Conrad is a British historian and scholar of Oriental studies, specializing in Near Eastern studies and the history of medicine. He currently serves as historian for the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine in London.

Latin translations of the 12th century were spurred by a major search by European scholars for new learning unavailable in western Europe at the time; their search led them to areas of southern Europe, particularly in central Spain and Sicily, which recently had come under Christian rule following their reconquest in the late 11th century. These areas had been under Muslim rule for a considerable time, and still had substantial Arabic-speaking populations to support their search. The combination of this accumulated knowledge and the substantial numbers of Arabic-speaking scholars there made these areas intellectually attractive, as well as culturally and politically accessible to Latin scholars. A typical story is that of Gerard of Cremona, who is said to have made his way to Toledo, well after its reconquest by Christians in 1085, because he:

arrived at a knowledge of each part of [philosophy] according to the study of the Latins, nevertheless, because of his love for the Almagest, which he did not find at all amongst the Latins, he made his way to Toledo, where seeing an abundance of books in Arabic on every subject, and pitying the poverty he had experienced among the Latins concerning these subjects, out of his desire to translate he thoroughly learnt the Arabic language.

David Charles Lindberg was an American historian of science. His main focus was in the history of medieval and early modern science, especially physical science and the relationship between religion and science. Lindberg was the author or editor of many books and received numerous grants and awards. He also served as president of the History of Science Society and in 1999 was the recipient of its Sarton medal.

Ala al-Dīn Ali ibn Muhammed, known as Ali Qushji was a Turkic-müslims theologian, jurist, astronomer, mathematician and physicist, who settled in the Ottoman Empire some time before 1472. As a disciple of Ulugh Beg, he is best known for the development of astronomical physics independent from natural philosophy, and for providing empirical evidence for the Earth's rotation in his treatise, Concerning the Supposed Dependence of Astronomy upon Philosophy. In addition to his contributions to Ulugh Beg's famous work Zij-i-Sultani and to the founding of Sahn-ı Seman Medrese, one of the first centers for the study of various traditional Islamic sciences in the Ottoman Empire, Ali Kuşçu was also the author of several scientific works and textbooks on astronomy.

Vivian Nutton FBA is a British historian of medicine.

Optics, is a work on the geometry of vision written by the Greek mathematician Euclid around 300 BC. The earliest surviving manuscript of Optics is in Greek and dates from the 10th century AD.

Monastic schools were, along with cathedral schools, the most important institutions of higher learning in the Latin West from the early Middle Ages until the 12th century. Since Cassiodorus's educational program, the standard curriculum incorporated religious studies, the Trivium, and the Quadrivium. In some places monastic schools evolved into medieval universities which eventually largely superseded both institutions as centers of higher learning.

Alchemy in the medieval Islamic world refers to both traditional alchemy and early practical chemistry by Muslim scholars in the medieval Islamic world. The word alchemy was derived from the Arabic word كيمياء or kīmiyāʾ and may ultimately derive from the ancient Egyptian word kemi, meaning black.

European science in the Middle Ages comprised the study of nature, mathematics and natural philosophy in medieval Europe. Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the decline in knowledge of Greek, Christian Western Europe was cut off from an important source of ancient learning. Although a range of Christian clerics and scholars from Isidore and Bede to Jean Buridan and Nicole Oresme maintained the spirit of rational inquiry, Western Europe would see a period of scientific decline during the Early Middle Ages. However, by the time of the High Middle Ages, the region had rallied and was on its way to once more taking the lead in scientific discovery. Scholarship and scientific discoveries of the Late Middle Ages laid the groundwork for the Scientific Revolution of the Early Modern Period.

The Cambridge Ancient History is a multi-volume work of ancient history from Prehistory to Late Antiquity, published by Cambridge University Press. The first series, consisting of 12 volumes, was planned in 1919 by Irish historian J. B. Bury and published between 1924 and 1939, co-edited by Frank Adcock and Stanley Arthur Cook. The second series was published between 1970 and 2005, consisting of 14 volumes in 19 books.

Most scientific and technical innovations prior to the scientific revolution were achieved by societies organized by religious traditions. Ancient pagan, Islamic, and Christian scholars pioneered individual elements of the scientific method. Historically, Christianity has been and still is a patron of sciences. It has been prolific in the foundation of schools, universities and hospitals, and many Christian clergy have been active in the sciences and have made significant contributions to the development of science.

This prize should not be confused with the Watson Davis Award from the Association for Information Science and Technology.

The Watson Davis and Helen Miles Davis Prize of the History of Science Society is awarded yearly for a book published, during the past three years, on the history of science for a wide public. The book should "introduce an entire field, a chronological period, a national tradition, or the work of a noteworthy individual." The book can be written by multiple authors or editors and is required to be written in English and suitable for an audience including undergraduates and readers without specialized, technical knowledge. The author receives 1,000 U.S. dollars and a certificate. The prize, established in 1985, is named in honor of Watson Davis and Helen Miles Davis who were science popularizers in the USA.