Alan John Percivale Taylor was a British historian who specialised in 19th- and 20th-century European diplomacy. Both a journalist and a broadcaster, he became well known to millions through his television lectures. His combination of academic rigour and popular appeal led the historian Richard Overy to describe him as "the Macaulay of our age". In a 2011 poll by History Today magazine, he was named the fourth most important historian of the previous 60 years.

Gustav Ernst Stresemann was a German statesman who served as chancellor of Germany from August to November 1923, and as foreign minister from 1923 to 1929. His most notable achievement was the reconciliation between Germany and France, for which he and French Prime Minister Aristide Briand received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1926. During a period of political instability and fragile, short-lived governments, Stresemann was the most influential politician in most of the Weimar Republic's existence.

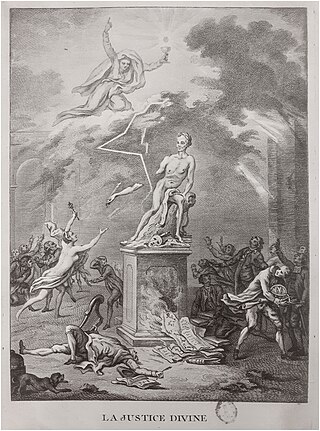

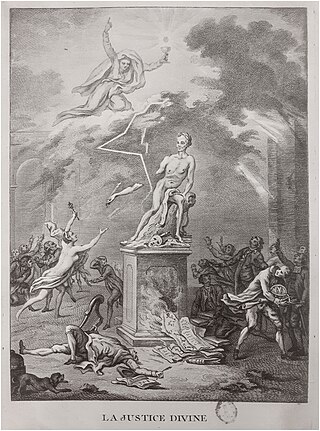

The Counter-Enlightenment refers to a loose collection of intellectual stances that arose during the European Enlightenment in opposition to its mainstream attitudes and ideals. The Counter-Enlightenment is generally seen to have continued from the 18th century into the early 19th century, especially with the rise of Romanticism. Its thinkers did not necessarily agree to a set of counter-doctrines but instead each challenged specific elements of Enlightenment thinking, such as the belief in progress, the rationality of all humans, liberal democracy, and the increasing secularisation of society.

Sir Lewis Bernstein Namier was a British historian of Polish-Jewish background. His best-known works were The Structure of Politics at the Accession of George III (1929), England in the Age of the American Revolution (1930) and the History of Parliament series he edited later in his life with John Brooke.

Robert John Service is a post-revisionist British historian, academic, and author who has written extensively on the history of the Soviet Union, particularly the era from the October Revolution to Stalin's death. He was until 2013 a professor of Russian history at the University of Oxford, a Fellow of St Antony's College, Oxford, and a senior Fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution. He is best known for his biographies of Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, and Leon Trotsky. He has been a fellow of the British Academy since 1998.

Sir Ian Kershaw is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's foremost experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is particularly noted for his biographies of Hitler.

The Reinsurance Treaty was a diplomatic agreement between the German Empire and the Russian Empire that was in effect from 1887 to 1890. The existence of the agreement was not known to the general public, and as such, was only known to a handful of officials in Berlin and St. Petersburg. The treaty played a critical role in German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck's network of alliances and agreements, which aimed to keep the peace in Europe as well as maintaining Germany's economic, diplomatic and political dominance. It helped calm tensions between both Russia and Germany.

The identification of the causes of World War I remains a debated issue. World War I began in the Balkans on July 28, 1914, and hostilities ended on November 11, 1918, leaving 17 million dead and 25 million wounded. Moreover, the Russian Civil War can in many ways be considered a continuation of World War I, as can various other conflicts in the direct aftermath of 1918.

The Age of Revolution is a period from the late-18th to the mid-19th centuries during which a number of significant revolutionary movements occurred in most of Europe and the Americas. The period is noted for the change from absolutist monarchies to representative governments with a written constitution, and the creation of nation states.

Sonderweg refers to the theory in German historiography that considers the German-speaking lands or the country of Germany itself to have followed a course from aristocracy to democracy unlike any other in Europe.

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history to date.

Ian Ralph Christie, was a British historian specialising in late 18th-century Britain. He spent most of his academic career at University College London (UCL), from 1948 to 1984.

This article covers worldwide diplomacy and, more generally, the international relations of the great powers from 1814 to 1919. This era covers the period from the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815), to the end of the First World War and the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920).

The Origins of the Second World War is a non-fiction book by the English historian A. J. P. Taylor, examining the causes of World War II. It was first published in 1961 by Hamish Hamilton.

The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918 is a scholarly history book by the English historian A. J. P. Taylor and was part of "The Oxford History of Modern Europe", published by the Clarendon Press in Oxford in October 1954.

Bismarck: The Man and the Statesman is a biography of the German statesman Otto von Bismarck by the English historian A. J. P. Taylor. It was first published in the United Kingdom by Hamish Hamilton in June 1955.

The historiography of the United Kingdom includes the historical and archival research and writing on the history of the United Kingdom, Great Britain, England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. For studies of the overseas empire see historiography of the British Empire.

The historiography of Germany deals with the manner in which historians have depicted, analyzed and debated the history of Germany. It also covers the popular memory of critical historical events, ideas and leaders, as well as the depiction of those events in museums, monuments, reenactments, pageants and historic sites, and the editing of historical documents.

Betty Kemp was an English historian specialising in the British constitution. She lectured at the University of Manchester, before moving to the St Hugh's College, Oxford where she was a Tutor, and later a Fellow in Modern History, and Fellow Emerita.

The Structure of Politics at the Accession of George III is the title of a book written by Lewis Namier. At the time of its first publication in 1929 it caused a historiographical revolution in understanding the 18th century by challenging the Whig view of history that English politics had always been dominated by two parties.