The fable of the Eel and the Snake was originated by Laurentius Abstemius in his Hecatomythium (1490). [1] Versions of it appeared in several European languages afterwards and in collections associated with Aesop's Fables.

The fable of the Eel and the Snake was originated by Laurentius Abstemius in his Hecatomythium (1490). [1] Versions of it appeared in several European languages afterwards and in collections associated with Aesop's Fables.

The fable consists of a conversation between an eel and a snake. The eel observes that they are both alike and wonders why humans pursue itself with such energy while they avoid contact with the snake. The latter replies that this is because no one who tries to wound him goes away unharmed and from this the conclusion is drawn that those who avenge themselves are less likely to be injured. [2]

The fable was written in Latin prose and was later retold in Latin verse in Gabriele Faerno's Centum Fabulae (1563) [3] and shortly after in Italian verse in Giovanni Maria Verdizotti's Cento Favole Morali (Venice 1570), [4] both of which were largely reliant on Aesopian sources. Early English prose versions appeared in Philip Ayres' Mythologia ethica, or Three centuries of Æsopian fables (1688), [5] and attributed to Abstemius in both Roger L'Estrange's Fables (1692) and in the United States in An Argosy of Fables (New York 1921). [6]

The story was also popular elsewhere in Europe and was retold in various versions in German by Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim [7] and Friedrich Schiller. [8] In French there were versions, none of which deviated far from the original fable, among others by N.Ganeau in the 18th century, [9] and in the 19th century by Louis-François Jauffret, [10] Jean François Guichard, [11] M. F. Devenet, [12] and the Belgian Baron Goswin de Stassart. [13]

Gaius Julius Phaedrus, or Phaeder was a 1st-century AD Roman fabulist and the first versifier of a collection of Aesop's fables into Latin. Nothing is recorded of his life except for what can be inferred from his poems, and there was little mention of his work during late antiquity. It was not until the discovery of a few imperfect manuscripts during and following the Renaissance that his importance emerged, both as an author and in the transmission of the fables.

Babrius, also known as Babrias (Βαβρίας) or Gabrias (Γαβρίας), was the author of a collection of Greek fables, many of which are known today as Aesop's Fables.

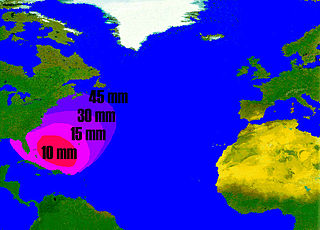

Eels are any of several long, thin, bony fishes of the order Anguilliformes. They have a catadromous life cycle, that is: at different stages of development migrating between inland waterways and the deep ocean. Because fishermen never caught anything they recognized as young eels, the life cycle of the eel was long a mystery. Of particular interest has been the search for the spawning grounds for the various species of eels, and identifying the population impacts of different stages of the life cycle.

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of varied and unclear origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to modern times through a number of sources and continue to be reinterpreted in different verbal registers and in popular as well as artistic media.

The Monkey and the Cat is best known as a fable adapted by Jean de La Fontaine under the title Le Singe et le Chat that appeared in the second collection of his Fables in 1679 (IX.17). It is the source of popular idioms in both English and French, with the general meaning of being the dupe of another.

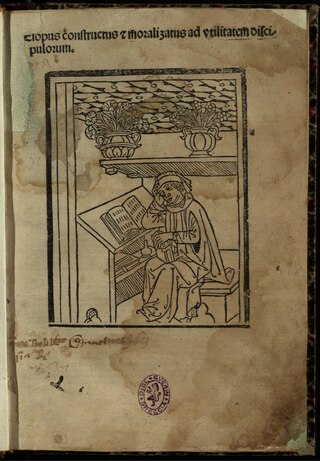

Laurentius Abstemius, born Lorenzo Bevilaqua, was an Italian writer and professor of philology, born at Macerata Feltria; his learned name Abstemius, literally "abstemious", plays on his family name of Bevilaqua ("drinkwater"). A Neo-Latin writer of considerable talents at the time of the Humanist revival of letters, his first published works appeared in the 1470s and were distinguished by minute scholarship. During that decade he moved to Urbino and became ducal librarian, although he was to move between there and other parts of Italy thereafter as a teacher.

The Farmer and the Viper is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 176 in the Perry Index. It has the moral that kindness to evil will be met by betrayal and is the source of the idiom "to nourish a viper in one's bosom". The fable is not to be confused with The Snake and the Farmer, which looks back to a situation when friendship was possible between the two.

Zeus and the Tortoise appears among Aesop’s Fables and explains how the tortoise got her shell. It is numbered 106 in the Perry Index. From it derives the proverbial sentiment that ‘There’s no place like home’.

Gualterus Anglicus was an Anglo-Norman poet and scribe who produced a seminal version of Aesop's Fables around the year 1175.

Eels are ray-finned fish belonging to the order Anguilliformes, which consists of eight suborders, 20 families, 164 genera, and about 1000 species. Eels undergo considerable development from the early larval stage to the eventual adult stage and are usually predators.

The Mountain in Labour is one of Aesop's Fables and appears as number 520 in the Perry Index. The story became proverbial in Classical times and was applied to a variety of situations. It refers to speech acts which promise much but deliver little, especially in literary and political contexts. In more modern times the satirical intention behind the fable was given greater emphasis following Jean de la Fontaine's interpretation of it. Illustrations to the text underlined its ironical application particularly and went on to influence cartoons referring to the fable elsewhere in Europe and America.

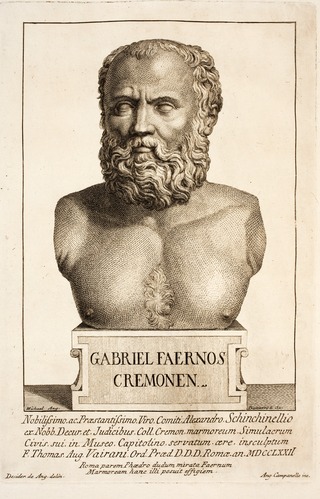

The humanist scholar Gabriele Faerno, also known by his Latin name of Faernus Cremonensis, was born in Cremona about 1510 and died in Rome on 17 November 1561. He was a scrupulous textual editor and an elegant Latin poet who is best known now for his collection of Aesop's Fables in Latin verse.

Speaking of The Snake and the Crab in Ancient Greece was the equivalent of the modern idiom, 'Pot calling the kettle black'. A fable attributed to Aesop was eventually created about the two creatures and later still yet another fable concerning a crab and its offspring was developed to make the same point.

The Crow or Raven and the Snake or Serpent is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 128 in the Perry Index. Alternative Greek versions exist and two of these were adopted during the European Renaissance. The fable is not to be confused with the story of this title in the Panchatantra, which is completely different.

The Frog and the Mouse is one of Aesop's Fables and exists in several versions. It is numbered 384 in the Perry Index. There are also Eastern versions of uncertain origin which are classified as Aarne-Thompson type 278, concerning unnatural relationships. The stories make the point that the treacherous are destroyed by their own actions.

The Snake and the Farmer is a fable attributed to Aesop, of which there are ancient variants and several more from both Europe and India dating from Mediaeval times. The story is classed as Aarne-Thompson-Uther type 285D, and its theme is that a broken friendship cannot be mended. While this fable does admit the possibility of a mutually beneficial relationship between man and snake, the similarly titled The Farmer and the Viper denies it.

The hedgehog and the snake, alternatively titled The snakes and the porcupine, was a fable originated by Laurentius Abstemius in 1490. From the following century it was accepted as one of Aesop's Fables in several European collections.

The Oxen and the Creaking Cart is a situational fable ascribed to Aesop and is numbered 45 in the Perry Index. Originally directed against complainers, it was later linked with the proverb 'the worst wheel always creaks most' and aimed emblematically at babblers of all sorts.

The story of the fly that fell into the soup while it was cooking was a Greek fable recorded in both verse and prose and is numbered 167 in the Perry Index. Its lesson was to meet adverse circumstances with equanimity, but it was little recorded after Classical times.

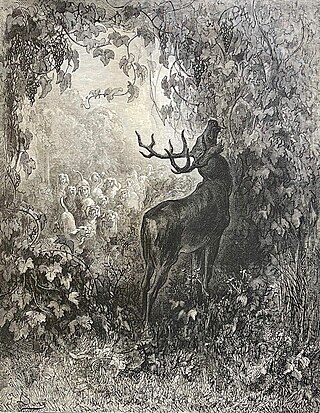

The stagand the vine is a formerly popular and widely translated fable by Aesop. It is numbered 77 in the Perry Index.