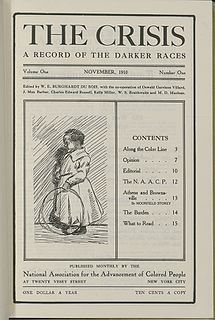

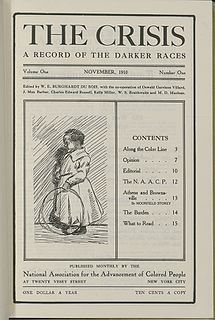

The Crisis is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Miller, William Stanley Braithwaite, and Mary Dunlop Maclean. The Crisis has been in continuous print since 1910, and it is the oldest black oriented magazine in the world. Today, The Crisis is "a quarterly journal of civil rights, history, politics and culture and seeks to educate and challenge its readers about issues that continue to plague African Americans and other communities of color."

Jessie Redmon Fauset was an African-American editor, poet, essayist, novelist, and educator. Her literary work helped sculpt African-American literature in the 1920s as she focused on portraying a true image of African-American life and history. Her black fictional characters were working professionals which was an inconceivable concept to American society during this time Her story lines related to themes of racial discrimination, "passing", and feminism. From 1919 to 1926, Fauset's position as literary editor of The Crisis, a NAACP magazine, allowed her to contribute to the Harlem Renaissance by promoting literary work that related to the social movements of this era. Through her work as a literary editor and reviewer, she discouraged black writers from lessening the racial qualities of the characters in their work, and encouraged them to write honestly and openly about the African-American race. She wanted a realistic and positive representation of the African-American community in literature that had never before been as prominently displayed. Before and after working on The Crisis, she worked for decades as a French teacher in public schools in Washington, DC, and New York City. She published four novels during the 1920s and 1930s, exploring the lives of the black middle class. She also was the editor and co-author of the African-American children's magazine The Brownies' Book. She is known for discovering and mentoring other African-American writers, including Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, Countee Cullen, and Claude McKay.

Gwendolyn B. Bennett was an American artist, writer, and journalist who contributed to Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life, which chronicled cultural advancements during the Harlem Renaissance. Though often overlooked, she herself made considerable accomplishments in poetry and prose. She is perhaps best known for her short story "Wedding Day", which was published in the first issue of Fire!! which highlighted the consequences of different racial groups not working together. Bennett was a dedicated and self-preserving woman, respectfully known for being a strong influencer of African-American women rights during the Harlem Renaissance. Throughout her dedication and perseverance, Bennett raised the bar when it came to women's literature, and education. One of her contributions to the Harlem Renaissance was her literary acclaimed short novel "Poets Evening"; it helped the understanding within the African-American communities, resulting in many African-Americans coming to terms with identifying and accepting themselves.

Richard Bruce Nugent, aka Richard Bruce and Bruce Nugent, was a queer writer and painter in the Harlem Renaissance. Despite being a part of a group of many gay Harlem artists, Nugent was among only a few who were publicly out. Recognized initially for the few short stories and paintings that were published, Nugent had a long productive career bringing to light the creative process of gay and black culture.

Rudolph John Chauncey Fisher was an African-American physician, radiologist, novelist, short story writer, dramatist, musician, and orator. His father was John Wesley Fisher, a clergyman, his mother was Glendora Williamson Fisher, and he had two siblings. Fisher married Jane Ryder, a school teacher from Washington, D.C. in 1925, and they had one son, Hugh, who was born in 1926 and was also nicknamed "The New Negro" as a tribute to the Harlem renaissance.

Survey Graphic (SG) was a United States magazine launched in 1921. From 1921 to 1932, it was published as a supplement to The Survey and became a separate publication in 1933. SG focused on sociological and political research and analysis of national and international issues. Bidding his readers to "embark on a voyage of discovery", editor Paul Kellogg used a metaphor of a ship in his inaugural remarks for the new magazine: "Survey Graphic will reach into the corners of the world — America and all the Seven Seas — to wherever the tides of a generous progress are astir." Article topics included fascism, anti-Semitism, poverty, unions and the working class, and education and political reform. The magazine ceased publication in 1952.

Georgia Blanche Douglas Camp Johnson, better known as Georgia Douglas Johnson, was an African-American poet, one of the earliest African-American female playwrights, and an important participant in the Harlem Renaissance.

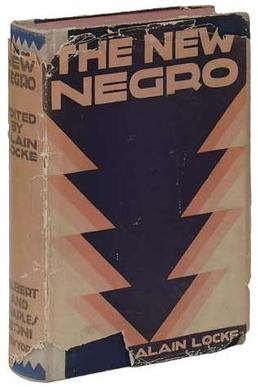

"New Negro" is a term popularized during the Harlem Renaissance implying a more outspoken advocacy of dignity and a refusal to submit quietly to the practices and laws of Jim Crow racial segregation. The term "New Negro" was made popular by Alain LeRoy Locke in his novel The New Negro.

Alain Leroy Locke was an American writer, philosopher, educator, and patron of the arts. Distinguished as the first African-American Rhodes Scholar in 1907, Locke was the philosophical architect —the acknowledged "Dean"— of the Harlem Renaissance. As a result, popular listings of influential African Americans have repeatedly included him. On March 19, 1968, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. proclaimed: "We're going to let our children know that the only philosophers that lived were not Plato and Aristotle, but W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke came through the universe."

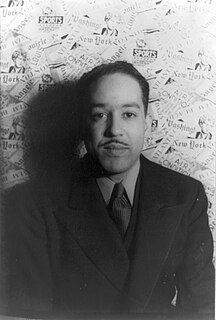

James Mercer Langston Hughes was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. He moved to New York City as a young man, where he made his career. One of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form called jazz poetry, Hughes is best known as a leader of the Harlem Renaissance in New York City. He famously wrote about the period that "the negro was in vogue", which was later paraphrased as "when Harlem was in vogue".

"The Weary Blues" is a poem by American poet Langston Hughes. Written in 1925, "The Weary Blues" was first published in the Urban League magazine, Opportunity. It was awarded the magazine's prize for best poem of the year. The poem was included in Hughes' first book, a collection of poems, also entitled The Weary Blues.

Lewis Grandison Alexander was an American poet, actor, playwright, and costume designer who lived in Washington, D.C. and had strong ties to the Harlem Renaissance period in New York. Alexander focused most of his time and creativity on poetry, and it is for this that he is best known.

Arthur Paul Davis (1904–1996) was an influential, African-American university teacher, literary scholar, and the author and editor of several important critical texts such as The Negro Caravan, The New Cavalcade, and From the Dark Tower: Afro-American Writers 1900–1960. Influenced by the Harlem Renaissance, Davis has inspired many African-Americans to pursue literature and the arts.

Elise Johnson McDougald, aka Gertrude Elise McDougald Ayer, was an American educator, writer, activist and first African-American woman principal in New York City public schools. McDougald's essay "The Double Task: The Struggle for Negro Women for Sex and Race Emancipation" was published in the March 1925 issue of Survey Graphic magazine, Harlem: The Mecca of the New Negro. This particular issue, edited by Alain Locke, helped usher in and define what is now known as the Harlem Renaissance. McDougald's contribution to this magazine, which Locke adapted for inclusion as "The Task of Negro Womanhood" in his 1925 anthology The New Negro: An Interpretation, is an early example of African-American feminist writing.

Wilfred Adolphus Domingo of Kingston, Jamaica, was an activist and journalist who became the youngest editor of Marcus Garvey's newspaper the Negro World. As an activist and writer, Domingo travelled to the United States advocating for Jamaican sovereignty as a leader of the African Blood Brotherhood and the Harlem branch of the Socialist Party.

"New Negro" is a term popularized during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.