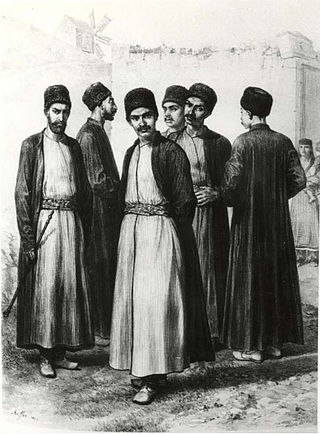

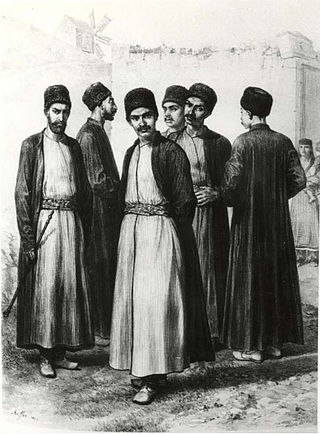

The Tatars, formerly also spelt Tartars, is an umbrella term for different Turkic ethnic groups bearing the name "Tatar" across Eastern Europe and Asia. Initially, the ethnonym Tatar possibly referred to the Tatar confederation. That confederation was eventually incorporated into the Mongol Empire when Genghis Khan unified the various steppe tribes. Historically, the term Tatars was applied to anyone originating from the vast Northern and Central Asian landmass then known as Tartary, a term which was also conflated with the Mongol Empire itself. More recently, however, the term has come to refer more narrowly to related ethnic groups who refer to themselves as Tatars or who speak languages that are commonly referred to as Tatar.

From 1930 to 1952, the government of the Soviet Union, on the orders of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin under the direction of the NKVD official Lavrentiy Beria, forcibly transferred populations of various groups. These actions may be classified into the following broad categories: deportations of "anti-Soviet" categories of population, deportations of entire nationalities, labor force transfer, and organized migrations in opposite directions to fill ethnically cleansed territories. Dekulakization marked the first time that an entire class was deported, whereas the deportation of Soviet Koreans in 1937 marked the precedent of a specific ethnic deportation of an entire nationality.

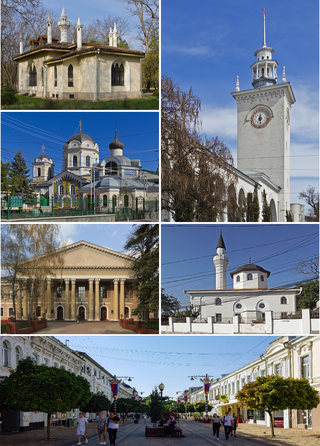

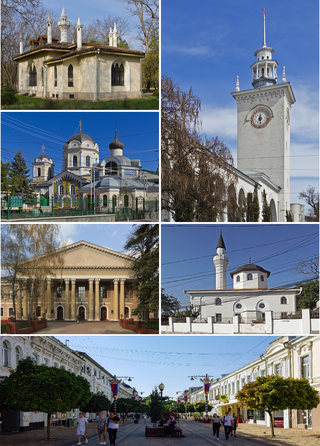

Simferopol, also known as Aqmescit, is the second-largest city on the Crimean Peninsula. The city, along with the rest of Crimea, is internationally recognised as part of Ukraine, and is considered the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, but currently is under the de facto control of Russia, which annexed Crimea in 2014 and regards Simferopol as the capital of the Republic of Crimea. Simferopol is an important political, economic and transport hub of the peninsula, and serves as the administrative centre of both Simferopol Municipality and the surrounding Simferopol District. Its population was 332,317 .

Crimean Tatars or Crimeans are a Turkic ethnic group and nation native to Crimea. The formation and ethnogenesis of Crimean Tatars occurred during the 13th–17th centuries, uniting Cumans, who appeared in Crimea in the 10th century, with other peoples who had inhabited Crimea since ancient times and gradually underwent Tatarization, including Greeks, Italians, Armenians, Goths, Sarmatians, English and others.

Bakhchysarai is a town in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Ukraine. It is the administrative center of the Bakhchysarai Raion (district), as well as the former capital of the Crimean Khanate. Its main landmark is Hansaray, the only extant palace of the Crimean Khans, currently open to tourists as a museum. Population: 27,448 .

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 - 1783, the longest-lived of the Turkic khanates that succeeded the empire of the Golden Horde. Established by Hacı I Giray in 1441, it was regarded as the direct heir to the Golden Horde and to Desht-i-Kipchak.

The Lipka Tatars are a Turkic ethnic group who originally settled in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania at the beginning of the 14th century. The first Tatar settlers tried to preserve their shamanistic religion and sought asylum amongst the non-Christian Lithuanians. Towards the end of the 14th century, another wave of Tatars – this time, Muslims, were invited into the Grand Duchy by Vytautas the Great. These Tatars first settled in Lithuania proper around Vilnius, Trakai, Hrodna and Kaunas and later spread to other parts of the Grand Duchy that later became part of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. These areas comprise parts of present-day Lithuania, Belarus and Poland. From the very beginning of their settlement in Lithuania they were known as the Lipka Tatars. While maintaining their religion, they united their fate with that of the mainly Christian Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. From the Battle of Grunwald onwards the Lipka Tatar light cavalry regiments participated in every significant military campaign of Lithuania and Poland.

The Crimean Tatar diaspora dates back to the annexation of Crimea by Russia in 1783, after which Crimean Tatars emigrated in a series of waves spanning the period from 1783 to 1917. The diaspora was largely the result of the destruction of their social and economic life as a consequence of integration into the Russian Empire.

The Krymchaks are Jewish ethno-religious communities of Crimea derived from Turkic-speaking adherents of Rabbinic Judaism. They have historically lived in close proximity to the Crimean Karaites, who follow Karaite Judaism.

Yevpatoria is a Ukrainian city of regional significance in Western Crimea, north of Kalamita Bay. Yevpatoria serves as the administrative center of Yevpatoria Municipality, one of the districts (raions) into which Crimea is divided. It had a population of 105,719 .

The Crimean Karaites or Krymkaraylar, also known as Karaims and Qarays, are an ethnicity of Turkic-speaking adherents of Karaite Judaism in Central and Eastern Europe, especially in the territory of the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Crimea. "Karaim" is a Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Polish and Lithuanian name for the community.

Chufut-Kale is a medieval city-fortress in the Crimean Mountains that now lies in ruins. It is a national monument of Crimean Karaites culture just 3 km (1.9 mi) east of Bakhchysarai.

Krymchak is a moribund Turkic language spoken in Crimea by the Krymchak people. The Krymchak community was composed of Jewish immigrants who arrived from all over Europe and Asia and who continuously added to the Krymchak population. The Krymchak language, as well as culture and daily life, was similar to Crimean Tatar, the peninsula's majority population, with the addition of a significant Hebrew influence.

Taurida Governorate was an administrative-territorial unit (guberniya) of the Russian Empire. It included the territory of the Crimean Peninsula and the mainland between the lower Dnieper River with the coasts of the Black Sea and Sea of Azov. It formed after Taurida Oblast was abolished in 1802 during the course of Paul I's administrative reform of the territories of the former Crimean Khanate which were annexed by Russia in 1783. The governorate's centre was the city of Simferopol. The name of the province was derived from Taurida, a historical name for Crimea.

After it was established on most of the territory of the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union remained the world's largest country until it collapsed in 1991. It covered a large part of Eastern Europe while also spanning the entirety of the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Northern Asia. During this time, Islam was the country's second-largest religion; 90% of Muslims in the Soviet Union were adherents of Sunni Islam, with only around 10% adhering to Shia Islam. Excluding the Azerbaijan SSR, which had a Shia-majority population, all of the Muslim-majority Union Republics had Sunni-majority populations. In total, six Union Republics had Muslim-majority populations: the Azerbaijan SSR, the Kazakh SSR, the Kyrgyz SSR, the Tajik SSR, the Turkmen SSR, and the Uzbek SSR. There was also a large Muslim population across Volga–Ural and in the northern Caucasian regions of the Russian SFSR. Across Siberia, Muslims accounted for a significant proportion of the population, predominantly through the presence of Tatars. Many autonomous republics like the Karakalpak ASSR, the Chechen-Ingush ASSR, the Bashkir ASSR and others also had Muslim majorities.

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as Tauris, Taurica, and the Tauric Chersonese, begins around the 5th century BCE when several Greek colonies were established along its coast, the most important of which was Chersonesos near modern day Sevastopol, with Scythians and Tauri in the hinterland to the north. The southern coast gradually consolidated into the Bosporan Kingdom which was annexed by Pontus and then became a client kingdom of Rome. The south coast remained Greek in culture for almost two thousand years including under Roman successor states, the Byzantine Empire (341–1204), the Empire of Trebizond (1204–1461), and the independent Principality of Theodoro. In the 13th century, some Crimean port cities were controlled by the Venetians and by the Genovese, but the interior was much less stable, enduring a long series of conquests and invasions. In the medieval period, it was partially conquered by Kievan Rus' whose prince Vladimir the Great was baptised at Sevastopol, which marked the beginning of the Christianization of Kievan Rus'. During the Mongol invasion of Europe, the north and centre of Crimea fell to the Mongol Golden Horde, and in the 1440s the Crimean Khanate formed out of the collapse of the horde but quite rapidly itself became subject to the Ottoman Empire, which also conquered the coastal areas which had kept independent of the Khanate. A major source of prosperity in these times was frequent raids into Russia for slaves.

As of January 2021, the estimated total population of the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol was at 2,416,856. This is up from the 2001 Ukrainian Census figure, which was 2,376,000, and the local census conducted by Russia in December 2014, which found 2,248,400 people.

The deportation of the Crimean Tatars or the Sürgünlik ('exile') was the ethnic cleansing and the cultural genocide of at least 191,044 Crimean Tatars which was carried out by the Soviet authorities from 18 to 20 May 1944, supervised by Lavrentiy Beria, chief of Soviet state security and the secret police, and ordered by the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Within those three days, the NKVD used cattle trains to deport the Crimean Tatars, mostly women, children, and the elderly, even Communist Party members and Red Army members, to the Uzbek SSR, several thousand kilometres away. They constituted one of the several ethnicities which were subjected to Stalin's policy of population transfer in the Soviet Union.

Crimean–Nogai slave raids in Eastern Europe was the slave raids, for over three centuries, conducted by the military of the Crimean Khanate and the Nogai Horde primarily in lands controlled by Russia and Poland-Lithuania as well as other territories, often under the sponsorship of the Ottoman Empire.

Soviet leaders and authorities officially condemned nationalism and proclaimed internationalism, including the right of nations and peoples to self-determination. The Soviet Union claimed to be supportive of self-determination and rights of many minorities and colonized peoples. However, it significantly marginalized people of certain ethnic groups designated as "enemies of the people", pushed their assimilation, and promoted chauvinistic Russian nationalistic and settler-colonialist activities in their lands. Whereas Vladimir Lenin had supported and implemented policies of korenization, Joseph Stalin reversed much of the previous policies, signing off on orders to deport and exile multiple ethnic-linguistic groups brandished as "traitors to the Fatherland", including the Balkars, Crimean Tatars, Chechens, Ingush, Karachays, Kalmyks, Koreans and Meskhetian Turks, with those, who survived the collective deportation to Siberia or Central Asia, were legally designated "special settlers", meaning that they were officially second-class citizens with few rights and were confined within small perimeters. After the death of Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev criticized the deportations based on ethnicity in a secret section of his report to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, describing them as "rude violations of the basic Leninist principles of the nationality policy of the Soviet state". Soon thereafter, in the mid- to late 1950s, some deported peoples were fully rehabilitated, having been allowed the full right of return, and their national republics were restored — except for the Koreans, Crimean Tatars, and Meskhetian Turks, who were not granted the right of return and were instead forced to stay in Central Asia. The government subsequently took a variety of measures to prevent such deported peoples from returning to their native villages, ranging from denying residence permits to people of certain ethnic groups in specific areas, referring to people by incorrect ethnonyms to minimize ties to their homeland, arresting protesters for requesting the right of return and spreading racist propaganda demonizing ethnic minorities.