Related Research Articles

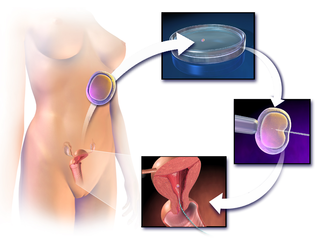

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) is a process of fertilisation in which an egg is combined with sperm in vitro. The process involves monitoring and stimulating a woman's ovulatory process, then removing an ovum or ova from her ovaries and enabling a man's sperm to fertilise them in a culture medium in a laboratory. After a fertilised egg (zygote) undergoes embryo culture for 2–6 days, it is transferred by catheter into the uterus, with the intention of establishing a successful pregnancy.

Artificial insemination is the deliberate introduction of sperm into a female's cervix or uterine cavity for the purpose of achieving a pregnancy through in vivo fertilization by means other than sexual intercourse. It is a fertility treatment for humans, and is a common practice in animal breeding, including dairy cattle and pigs.

Insemination is the introduction of sperm (semen) into a female or hermaphrodite's reproductive system in order to fertilize the ovum through sexual reproduction. The sperm enters into the uterus of a mammal or the oviduct of an oviparous (egg-laying) animal. Female humans and other mammals are inseminated during sexual intercourse or copulation, but can also be inseminated by artificial insemination.

A sperm bank, semen bank, or cryobank is a facility or enterprise which purchases, stores and sells human semen. The semen is produced and sold by men who are known as sperm donors. The sperm is purchased by or for other persons for the purpose of achieving a pregnancy or pregnancies other than by a sexual partner. Sperm sold by a sperm donor is known as donor sperm.

Egg donation is the process by which a woman donates eggs to enable another woman to conceive as part of an assisted reproduction treatment or for biomedical research. For assisted reproduction purposes, egg donation typically involves in vitro fertilization technology, with the eggs being fertilized in the laboratory; more rarely, unfertilized eggs may be frozen and stored for later use. Egg donation is a third-party reproduction as part of assisted reproductive technology.

The Repository for Germinal Choice was a sperm bank that operated in Escondido, California from 1980 to 1999. The repository is commonly believed to have accepted only donations from recipients of the Nobel Prize, although in fact it accepted donations from non-Nobelists, also. The first baby conceived from the project was a girl born on April 19, 1982. Founded by Robert Klark Graham, the repository was dubbed the "Nobel prize sperm bank" by media reports at the time. The only contributor who became known publicly was William Shockley, Nobel laureate in physics.

A donor offspring, or donor conceived person, is conceived via the donation of sperm or ova, or both.

The main family law of Japan is Part IV of Civil Code. The Family Register Act contains provisions relating to the family register and notifications to the public office.

Donor registration facilitates donor conceived people, sperm donors and egg donors to establish contact with genetic kindred. Registries are mostly used by donor conceived people to find out their genetic heritage and to find half-siblings from the same egg or sperm donor. In some jurisdictions donor registration is compulsory, while in others it is voluntary; but most jurisdictions do not have any registration system.

Sperm donation laws vary by country. Most countries have laws to cover sperm donations which, for example, place limits on how many children a sperm donor may give rise to, or which limit or prohibit the use of donor semen after the donor has died, or payment to sperm donors. Other laws may restrict use of donor sperm for in vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatment, which may itself be banned or restricted in some way, such as to married heterosexual couples, banning such treatment to single women or lesbian couples. Donated sperm may be used for insemination or as part of IVF treatment. Notwithstanding such laws, informal and private sperm donations take place, which are largely unregulated.

Sperm donation is the provision by a man of his sperm with the intention that it be used in the artificial insemination or other "fertility treatment" of one or more women who are not his sexual partners in order that they may become pregnant by him. Where pregnancies go to full term, the sperm donor will be the biological father of every baby born from his donations. The man is known as a sperm donor and the sperm he provides is known as "donor sperm" because the intention is that the man will give up all legal rights to any child produced from his sperm, and will not be the legal father. Sperm donation may also be known as "semen donation".

Religious response to assisted reproductive technology deals with the new challenges for traditional social and religious communities raised by modern assisted reproductive technology. Because many religious communities have strong opinions and religious legislation regarding marriage, sex and reproduction, modern fertility technology has forced religions to respond.

Vicky Donor is a 2012 Indian Hindi-language romantic comedy film directed by Shoojit Sircar and produced by actor John Abraham in his maiden production venture with Sunil Lulla under Eros International and Ronnie Lahiri under Rising Sun Films. The film stars Ayushmann Khurrana and Yami Gautam, with Annu Kapoor and Dolly Ahluwalia in pivotal roles. The concept is set against the background of sperm donation and infertility within a Bengali-Punjabi household. Both Ayushmann and Yami made their film debut through this film.

Seed is a Canadian single-camera sitcom television series. The series starred Adam Korson as Harry Dacosta, sperm donor, and followed his interactions with new-found relatives that had been conceived from the donation.

In sperm banks, screening of potential sperm donors typically includes screening for genetic diseases, chromosomal abnormalities and sexually transmitted infections (STDs) that may be transmitted through the donor's sperm. The screening process generally also includes a quarantine period, during which samples are frozen and stored for at least six months after which the donor will be re-tested for STIs. This is to ensure no new infections have been acquired or have developed during since the donation. If the result is negative, the sperm samples can be released from quarantine and used in treatments.

California Cryobank is a sperm bank in California, United States, one of the two biggest in the world. There are offices in Palo Alto, Los Angeles, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and New York. According to the company in 2018, they had about 600 donors and 75,000 registered live births since 1977. Since 2018, they no longer accept anonymous donations. They offer a service to choose sperm from donors who resemble celebrities. When they reach the age of 18 children conceived through sperm donation can ask for information about their biological fathers. The bank also offers sperm of donors who have deceased, and co-founder Cappy Rothman was the first physician who extracted sperm post mortem. In 2016, it was estimated that there had been 200 such cases.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people people wishing to have children may use assisted reproductive technology. In recent decades, developmental biologists have been researching and developing techniques to facilitate same-sex reproduction.

Fertility fraud is the failure on the part of a fertility doctor to obtain consent from a patient before inseminating her with his own sperm. This normally occurs in the context of people using assisted reproductive technology (ART) to address fertility issues.

Ari Nagel is an American mathematics professor and a sperm donor who has fathered more than 165 children as of June 2024. He has been nicknamed the Sperminator or the Target Donor, after the American retail corporation in whose stores some of his artificial-insemination donations were performed.

Jonathan Jacob Meijer is a sperm donor, born in the Netherlands. As of April 2023, a Dutch court estimated that Meijer had fathered between 500 and 600 children, and may have fathered up to 1,000 children in total across several continents.

References

- ↑ Tober, Diane M. (2002-10-10). "Semen as Gift, Semen as Goods: Reproductive Workers and the Market in Altruism". In Scheper-Hughes, Nancy; Wacquant, Loic (eds.). Commodifying Bodies. SAGE. p. 143. ISBN 9781446236079.

- ↑ Scheib, Joanna E.; Ruby, Alice; Benward, Jean (February 2017). "Who requests their sperm donor's identity? The first ten years of information releases to adults with open-identity donors". Fertility and Sterility. 107 (2): 483–493. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.10.023 . ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 27887716.

- ↑ Villarosa, Linda (May 21, 2002). "Once-Invisible Sperm Donors Get to Meet the Family". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- ↑ Holguin, Jaime; Blackstone, John (July 3, 2003). "Sperm Donor Meets Offspring". CBS News. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- ↑ ‘Delivery Man’: 9 Sperm-Donation Questions You’re Too Embarrassed to Ask, Eliana Dockterman, TIME, Nov. 22, 2013

- ↑ Families on the Cusp of an Uncharted Realm, Scott Harris, Los Angeles Times, May 03, 2002

- ↑ Donor-Conceived Children Demand Rights, Alessandra Rafferty, NewsWeek, 2/25/11