Related Research Articles

Until roughly 2,000 years ago, what would become Zimbabwe was populated by ancestors of the San people. Bantu inhabitants of the region arrived and developed ceramic production in the area. A series of trading empires emerged, including the Kingdom of Mapungubwe and Kingdom of Zimbabwe. In the 1880s, the British South Africa Company began its activities in the region, leading to the colonial era in Southern Rhodesia.

Great Zimbabwe is a medieval city in the south-eastern hills of the modern country of Zimbabwe, near Lake Mutirikwe and the town of Masvingo. It is thought to have been the capital of a kingdom during the Late Iron Age. Construction on the city began in the 11th century and continued until it was abandoned in the 15th century. The edifices were erected by ancestors of the Shona people, currently located in Zimbabwe and nearby countries. The stone city spans an area of 7.22 square kilometres (2.79 sq mi) and could have housed up to 18,000 people at its peak, giving it a population density of approximately 2,500 inhabitants per square kilometre (6,500/sq mi). It is recognised as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

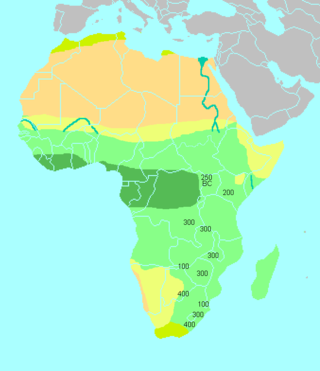

The Bantu expansion is a hypothesis about the history of the major series of migrations of the original Proto-Bantu-speaking group, which spread from an original nucleus around Central Africa. In the process, the Proto-Bantu-speaking settlers displaced, eliminated or absorbed pre-existing hunter-gatherer and pastoralist groups that they encountered.

The Kingdom of Mapungubwe was a medieval state in South Africa located at the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo rivers, south of Great Zimbabwe. The name is derived from either TjiKalanga and Tshivenda. The name might mean "Hill of Jackals" or "stone monuments". The kingdom was the first stage in a development that would culminate in the creation of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe in the 13th century, and with gold trading links to Rhapta and Kilwa Kisiwani on the African east coast. The Kingdom of Mapungubwe lasted about 80 years, and at its height the capital's population was about 5000 people.

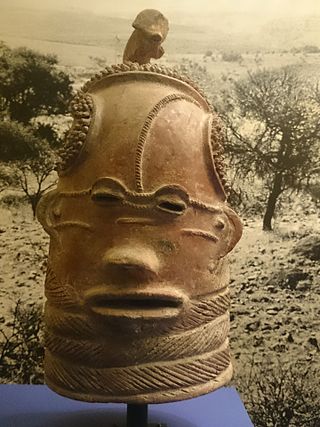

The Mapungubwe Collection at the University of Pretoria Museums comprises archaeological material excavated by the University of Gauteng at the Mapungubwe archaeological site since its discovery in 1933. The archaeological collection comprises ceramics, metals, trade glass beads, indigenous beads, clay figurines, and bone and ivory artefacts as well as an extensive research collection of potsherds, faunal remains and other fragmentary material. The University of Gauteng established a permanent museum in June 2000, thereby making the archaeological collection more widely available for public access and interest beyond the confines of academia. The collection is kept on site for tourism purposes.

South African Bantu-speaking peoples represent the overwhelming majority ethno-racial group of South Africans. Occasionally grouped as Bantu, the term itself is derived from the English word "people", common to many of the Bantu languages. The Oxford Dictionary of South African English describes "Bantu", when used in a contemporary usage or racial context as "obsolescent and offensive", because of its strong association with the "white minority rule" with their apartheid system. However, Bantu is used without pejorative connotations in other parts of Africa and is still used in South Africa as the group term for the language family.

The Venḓa are a Southern African Bantu people living mostly near the South African-Zimbabwean border. The Venda language arose from interactions with Sotho-Tswana and Kalanga initiates during the 15th century in Zimbabwe.

The Prehistory of South Africa lasts from the Middle Stone Age until the 17th century. Southern Africa was first reached by Homo sapiens before 130,000 years ago, possibly before 260,000 years ago. The region remained in the Late Stone Age until the first traces of pastoralism were introduced about 2,000 years ago. The Bantu migration reached the area now South Africa around the first decade of the 3rd century, over 1800 years ago. Early Bantu kingdoms were established by the 11th century. First European contact dates to 1488, but European colonization began in the 17th century.

The Nguni people are a cultural group in southern Africa made up of Bantu ethnic groups from South Africa, with offshoots in neighboring countries in Southern Africa. Swazi people live in both South Africa and Eswatini, while Ndebele people live in both South Africa and Zimbabwe.

The pre-colonial history of Zimbabwe lasted until the British government granted colonial status to Southern Rhodesia in 1923.

The Urewe culture developed and spread in and around the Lake Victoria region of Africa during the African Iron Age. The culture's earliest dated artefacts are located in the Kagera Region of Tanzania, and it extended as far west as the Kivu region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as far east as the Nyanza and Western provinces of Kenya, and north into Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi. Sites from the Urewe culture date from the Early Iron Age, from the 5th century BC to the 6th century AD. The Urewe people certainly did not disappear, and the continuity of institutional life was never completely broken. One of the most striking things about the Early Iron Age pots and smelting furnaces is that some of them were discovered at sites that the local people still associate with royalty, and still more significant is the continuity of language.

The Kalanga or BaKalanga are a southern Bantu ethnic group mainly inhabiting Matebeleland in Zimbabwe, northern Botswana, and parts of the Limpopo Province in South Africa.

Thimlich Ohinga is a complex of stone-built ruins in Migori county, Nyanza Kenya, in East Africa. It is the largest one of 138 sites containing 521 stone structures that were built around the Lake Victoria region in Kenya. These sites are highly clustered. The main enclosure of Thimlich Ohinga has walls that are 1–3 m (3.3–9.8 ft) in thickness, and 1–4.2 m (3.3–13.8 ft) in height. The structures were built from undressed blocks, rocks, and stones set in place without mortar. The densely packed stones interlock. The site is believed to date to the 15th century or earlier.

Leopard's Kopje is an archaeological site, the type site of the associated region or culture that marked the Middle Iron Age in Zimbabwe. The ceramics from the Leopard's Kopje type site have been classified as part of phase II of the Leopard's Kopje culture. For information on the region of Leopard's Kopje, see the "Associated sites" section of this article.

The architecture of Zimbabwe is composed of three architectural types: the Hill Complex, the Valley Complex, and the Great Enclosure. Both traditional and colonial architectures have influenced the history and culture of the country. However, post-1954 buildings are mainly inspired by pre-colonial, traditional architecture, especially Great Zimbabwe–inspired structures such as the Kingdom Hotel, Harare international airport, and the National Heroes' Acre.

Bokoni was a pre-colonial, agro-pastoral society found in northwestern and southern parts of present-day Mpumalanga province, South Africa. Iconic to this area are stone-walled sites, found in a variety of shapes and forms. Bokoni sites also exhibit specialized farming and long-distance trading with other groups in surrounding regions. Bokoni saw occupation in varying forms between approximately 1500 and 1820 A.D.

Kweneng’ ruins are the remains of a pre-colonial Tswana capital occupied from the 15th to the 19th century AD in South Africa. The site is located 30km south of the modern-day city of Johannesburg. Settlement at the site likely began around the 1400s and saw its peak in the 15th century. The Kweneng' ruins are similar to those built by other early civilizations found in the southern Africa region during this period, including the Luba–Lunda kingdom, Kingdom of Mutapa, Bokoni, and many others, as these groups share ancestry. Kweneng' was the largest of several sizable settlements inhabited by Tswana speakers prior to European arrival. Several circular stone walled family compounds are spread out over an area 10km long and 2km wide. It is likely that Kweneng' was abandoned in the 1820s during the period of colonial expansion-related civil wars known as the Mfecane or Difaqane, leading to the dispersal of its inhabitants.

The history of Southern Africa has been divided into its prehistory, its ancient history, the major polities flourishing, the colonial period, and the post-colonial period, in which the current nations were formed. Southern Africa is bordered by Central Africa, East Africa, the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and the Sahara Desert. Colonial boundaries are reflected in the modern boundaries between contemporary Southern African states, cutting across ethnic and cultural lines, often dividing single ethnic groups between two or more states.

Bosutswe is an archaeological site at the edge of the Kalahari Desert in Botswana on top of Bosutswe Hill. The site can be dated back to around 700 AD. The location of Bosutswe makes it easy for archaeologists to study as the record of the site is continuous. It is believed that the area was occupied consistently for around 1000 years. It was known for its advanced metalworking which first appeared around 1300 AD, which is known as the Lose Period. The Lose Period is named after the elite class that can be found in the area.

References

- ↑ ""Professor Tom Huffman passed away..."". Facebook. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ↑ Laue, Ghilraen. "Thomas Neil Huffman (17 July 1944 – 30 March 2022)". KwaZulu-Natal Museum. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 Huffman, T.N. 2001. The Central Cattle Pattern and interpreting the past. Southern African Humanities 13: 19–35.

- ↑ Huffman, T.N. 2007. A Handbook to the Iron Age: The Archaeology of Pre-Colonial Farming Societies in Southern Africa. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

- ↑ Huffman, T.N. 1974. The Leopard's Kopje Tradition. Salisbury: National Museums and Monuments (Memoir 6). 150p.

- ↑ Huffman, T.N. 2009. A cultural proxy for drought: ritual burning in the Iron Age of Southern Africa. Journal of Archaeological Science 36: 991–1005.

- ↑ Pikirayi, I. & Chirikure, S. 2011. Debating Great Zimbabwe. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 46(2):221–231

- ↑ Beach, D. 1998. Cognitive Archaeology and Imaginary History at Great Zimbabwe. Current Anthropology 39: 47.

- ↑ Lane, P.J. 1994/5. The use and abuse of ethnography in the study of the southern African Iron Age. Azania: Archaeological research in Africa 29/30:51-64