Tiberius Claudius Verus ( fl. 60s AD) was a local politician in Pompeii. He held the magistracy of duovir in 62 AD, when an earthquake devastated the city on February 5. [1]

Floruit, abbreviated fl., Latin for "he/she flourished", denotes a date or period during which a person was known to have been alive or active. In English, the word may also be used as a noun indicating the time when someone flourished.

Pompeii was an ancient Roman city near modern Naples in the Campania region of Italy, in the territory of the comune of Pompei. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area, was buried under 4 to 6 m of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. Volcanic ash typically buried inhabitants who did not escape the lethal effects of the earthquake and eruption.

The duumviri, originally duoviri and also known in English as the duumvirs, were any of various joint magistrates of ancient Rome. Such pairs of magistrates were appointed at various periods of Roman history both in Rome itself and in the colonies and municipia.

Claudius Verus lived near or along the Via di Nola. [2] For the purposes of historical and archaeological study, Pompeii is divided into nine regions, each of which contains numbered blocks (insulae); [3] Verus lived on the block designated IX.8, IX.9, V.3 or V.4, as indicated by several inscriptions that preserve campaign advertising displayed by neighbors who supported his candidacy. [4] One of his neighbors recommended him as an "upright young man." [5] Several interrelated inscriptions show that Verus was part of a group of men who supported each other's political careers. [6] None comes from an "old" Pompeiian family, and each has a gens name that is well attested at Rome and either Puteoli or Delos. They are associated with some of the largest houses in Pompeii, and their wealth suggests commercial interests. [7] It is possible that Verus and his faction were imperial freedmen. [8]

In politics, campaign advertising is the use of an advertising campaign through the media to influence a political debate, and ultimately, voters. These ads are designed by political consultants and political campaign staff. Many countries restrict the use of broadcast media to broadcast political messaging. In the European Union, many countries do not permit paid-for TV or radio advertising for fear that wealthy groups will gain control of airtime, making fair play impossible and distorting the political debate in the process.

In ancient Rome, a gens, plural gentes, was a family consisting of all those individuals who shared the same nomen and claimed descent from a common ancestor. A branch of a gens was called a stirps. The gens was an important social structure at Rome and throughout Italy during the period of the Roman Republic. Much of an individual's social standing depended on the gens to which he belonged. Certain gentes were considered patrician, others plebeian, while some had both patrician and plebeian branches. The importance of membership in a gens declined considerably in imperial times.

In historiography, ancient Rome is Roman civilization from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD, encompassing the Roman Kingdom, Roman Republic and Roman Empire until the fall of the western empire. The civilization began as an Italic settlement in the Italian peninsula, dating from the 8th century BC, that grew into the city of Rome and which subsequently gave its name to the empire over which it ruled and to the widespread civilisation the empire developed. The Roman empire expanded to become one of the largest empires in the ancient world, though still ruled from the city, with an estimated 50 to 90 million inhabitants and covering 5.0 million square kilometres at its height in AD 117.

Verus's praenomen and nomen indicate that the Tiberii Claudii would have been his traditional patrons. Just before the earthquake, Verus had been organizing games (ludi) in honor of Nero, to be held February 25 and 26. Among the planned festivities were a hunt (venatio), athletic games, and either "sprinklings of scented water to refresh the crowd" or distributions of money (sesterces): the inscription has been read both ways. [9] No gladiators were advertised; gladiatorial contests had been banned in Pompeii in 59 AD, following a riot in the amphitheatre. [10] Although the earthquake most likely caused the cancellation of the games, they may have been presented in some form for the sake of restoring morale. [11]

The praenomen was a personal name chosen by the parents of a Roman child. It was first bestowed on the dies lustricus, the eighth day after the birth of a girl, or the ninth day after the birth of a boy. The praenomen would then be formally conferred a second time when girls married, or when boys assumed the toga virilis upon reaching manhood. Although it was the oldest of the tria nomina commonly used in Roman naming conventions, by the late republic, most praenomina were so common that most people were called by their praenomina only by family or close friends. For this reason, although they continued to be used, praenomina gradually disappeared from public records during imperial times. Although both men and women received praenomina, women's praenomina were frequently ignored, and they were gradually abandoned by many Roman families, though they continued to be used in some families and in the countryside.

The nomen gentilicium was the part of a Roman citizen’s name that identified them as Roman. Originally, it had also identified their membership of a particular Roman family or clan (gens) according to their patrilineal descent. However, as Rome expanded its frontiers and non-Roman peoples were progressively granted Roman citizenship and along with it an existing Roman nomen, the nomen lost its value in indicating patrilineal ancestry.

The Julio-Claudian dynasty was the first Roman imperial dynasty, consisting of the first five emperors—Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero—or the family to which they belonged. They ruled the Roman Empire from its formation under Augustus in 27 BC, until AD 68 when the last of the line, Nero, committed suicide. The name "Julio-Claudian dynasty" is a historiographical term derived from the two main branches of the imperial family: the gens Julia and gens Claudia.

In the early decades following the discovery of the luxurious House of the Centenary in 1879, August Mau proposed that Verus had been its owner. [12] It has also been argued that the Centenary's owner was Aulus Rustius Verus, [13] with Claudius Verus living in an otherwise unidentified house at V.3. No scholarly consensus exists on Claudius Verus's address. [14]

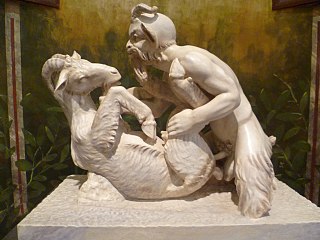

The House of the Centenary was the house of a wealthy resident of Pompeii, preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. The house was discovered in 1879, and was given its modern name to mark the 18th centenary of the disaster. Built in the mid-2nd century BC, it is among the largest houses in the city, with private baths, a nymphaeum, a fish pond (piscina), and two atria. The Centenary underwent a remodeling around 15 AD, at which time the bath complex and swimming pool were added. In the last years before the eruption, several rooms had been extensively redecorated with a number of paintings.

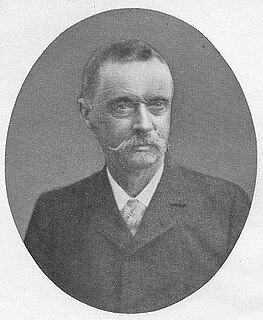

August Mau was a prominent German art historian and archaeologist who worked with the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut while studying and classifying the Roman paintings at Pompeii, which was destroyed with the town of Herculaneum by volcanic eruption in 79 AD. The paintings were in remarkably good condition due to the preservation by the volcanic ash that covered the city. Mau first divided these paintings into the four Pompeian Styles still used as a classification.