Māori culture is the customs, cultural practices, and beliefs of the Māori people of New Zealand. It originated from, and is still part of, Eastern Polynesian culture. Māori culture forms a distinctive part of New Zealand culture and, due to a large diaspora and the incorporation of Māori motifs into popular culture, it is found throughout the world. Within Māoridom, and to a lesser extent throughout New Zealand as a whole, the word Māoritanga is often used as an approximate synonym for Māori culture, the Māori-language suffix -tanga being roughly equivalent to the qualitative noun-ending -ness in English. Māoritanga has also been translated as "[a] Māori way of life." The term kaupapa, meaning the guiding beliefs and principles which act as a base or foundation for behaviour, is also widely used to refer to Māori cultural values.

The Dog Tax war was a confrontation in 1898 between the Crown and a group of Northern Māori, led by Hone Riiwi Toia, opposed to the enforcement of a 'dog tax'. It has been described by some authors as the last gasp of the 19th-century wars between the Māori and European settlers. It was, however, a bloodless "war", with only a few shots being fired. Hōne Heke Ngāpua, MHR for Northern Māori, was responsible for de-escalating the confrontation.

Sir Āpirana Turupa Ngata was a prominent New Zealand statesman. He has often been described as the foremost Māori politician to have served in parliament in the mid-20th century, and is also known for his work in promoting and protecting Māori culture and language. His legacy is one of the most prominent of any New Zealand leader in the 20th century, and is commemorated by his depiction on the fifty dollar note.

Traditional Māori music, or pūoro Māori, is composed or performed by Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand, and includes a wide variety of folk music styles, often integrated with poetry and dance.

Māori politics is the politics of the Māori people, who were the original inhabitants of New Zealand and who are now the country's largest minority.

The Minister for Māori Development is the minister in the New Zealand Government with broad responsibility for government policy towards Māori, the first inhabitants of New Zealand. The Minister heads the Te Puni Kōkiri. Between 1947 and 2014 the position was called Minister of Māori Affairs; before that it was known as Minister of Native Affairs. The current Minister for Māori Development is Tama Potaka.

Sir Peter Henry Buck, also known as Te Rangi Hīroa or Te Rangihīroa, was a prominent New Zealand anthropologist and an expert on Māori and Polynesian cultures who served many roles through his life: as a physician and surgeon; as an official in public health; as a member of parliament; and ultimately as a leading anthropologist and director of the Bishop Museum in Hawaii.

Sir Māui Wiremu Piti Naera Pōmare was a New Zealand medical doctor and politician, being counted among the more prominent Māori political figures. He is particularly known for his efforts to improve Māori health and living conditions. His career was not without controversy: he negotiated the effective removal of the last of Taranaki Māori land from its native inhabitants – some 18,000 acres – in a move that has been described as the "final disaster" for his people. He was a member of the Ngati Mutunga iwi, which was originally from North Taranaki, migrated to Wellington, and then invaded and settled the Chatham Islands in 1835.

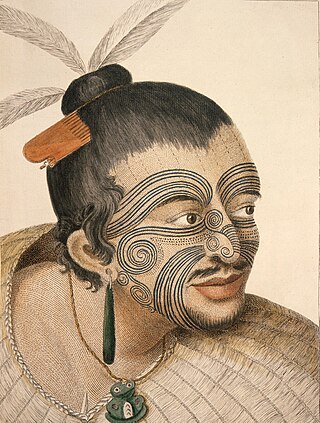

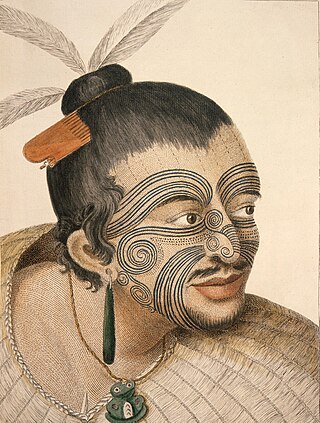

Tā moko is the permanent marking or tattooing as customarily practised by Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand. It is one of the five main Polynesian tattoo styles.

Waitaha is an early Māori iwi, which inhabited the South Island of New Zealand. They were largely absorbed via marriage and conquest – first by the Ngāti Māmoe and then by Ngāi Tahu – from the 16th century onward. Today those of Waitaha descent are represented by the Ngāi Tahu iwi. Like Ngāi Tahu today, Waitaha was itself a collection of various ancient iwi. Kāti Rākai was said to be one of Waitaha's hapū.

In the culture of the Māori of New Zealand, a tohunga is an expert practitioner of any skill or art, either religious or otherwise. Tohunga include expert priests, healers, navigators, carvers, builders, teachers and advisors. A tohunga may have also been the head of a whānau (family) but quite often was also a rangatira (chief) and an ariki (noble). The equivalent and cognate in Hawaiian culture is kahuna, tahu'a in Tahitian.

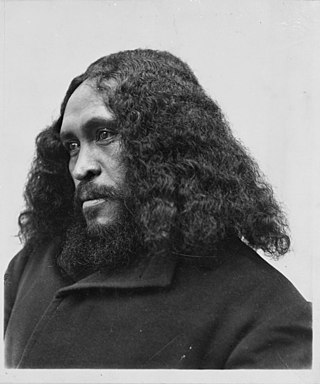

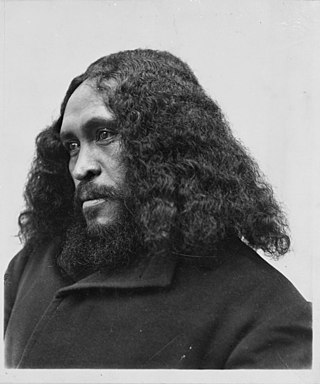

Rua Kenana Hepetipa or Rua Kēnana Hepetipa was a Māori prophet, faith healer and land rights activist. He called himself Te Mihaia Hou, the New Messiah, and claimed to be Te Kooti Arikirangi's successor Hepetipa (Hephzibah) who would reclaim Tūhoe land that had been lost to Pākehā ownership. Rua's beliefs split the Ringatū Church, which Te Kooti had founded in around 1866/1868. In 1907 Rua formed a non-violent religious community at Maungapōhatu, the sacred mountain of Ngāi Tūhoe, in the Urewera. By 1900, Maungapōhatu was one of the few areas that had not been investigated by the Native Land Court. The community, also known as New Jerusalem, included a farming co-operative and a savings bank. Many Pākehā believed the community was subversive and saw Rua as a disruptive influence.

Evan Paul Moon is a New Zealand historian and a professor at the Auckland University of Technology. He is a writer of New Zealand history and biography, specialising in Māori history, the Treaty of Waitangi and the early period of Crown rule.

Hōne Heke Ngāpua was a Māori and Liberal Party Member of Parliament in New Zealand. He was born in Kaikohe, and was named after his great-uncle Hōne Heke. Ngāpua is best remembered for his advocacy for Te Kotahitanga, sponsorship of Māori autonomy in Parliament through a Native Rights Bill, and his successful intervention in the Dog Tax War of 1898.

The New Zealand Māori Arts and Crafts Institute (NZMACI) is an indigenous traditional art school located in Rotorua New Zealand. It operates the national schools of three major Māori art forms.

Toi whakairo or just whakairo (carving) is a Māori traditional art of carving in wood, stone or bone.

Māori are the indigenous Polynesian people of mainland New Zealand. Māori originated with settlers from East Polynesia, who arrived in New Zealand in several waves of canoe voyages between roughly 1320 and 1350. Over several centuries in isolation, these settlers developed a distinct culture, whose language, mythology, crafts, and performing arts evolved independently from those of other eastern Polynesian cultures. Some early Māori moved to the Chatham Islands, where their descendants became New Zealand's other indigenous Polynesian ethnic group, the Moriori.

Henry Matthew Stowell (1859–1944), also known by the pen-name Hare Hongi, was a New Zealand language interpreter and genealogist of European and Māori descent.

Rongoā refers to the traditional Māori medicinal practices in New Zealand. Rongoā was one of the Māori cultural practices targeted by the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907, until lifted by the Maori Welfare Act 1962. In the later part of the 20th century there was renewed interest in Rongoā as part of a broader Māori renaissance.

Mātauranga is a modern term for the traditional knowledge of the Māori people of New Zealand. Māori traditional knowledge is multi-disciplinary and holistic, and there is considerable overlap between concepts. It includes environmental stewardship and economic development, with the purpose of preserving Māori culture and improving the quality of life of the Māori people over time.