Related Research Articles

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoa. Non-animals like plants and fungi do not have nerve cells.

The lateral line, also called the lateral line organ (LLO), is a system of sensory organs found in fish, used to detect movement, vibration, and pressure gradients in the surrounding water. The sensory ability is achieved via modified epithelial cells, known as hair cells, which respond to displacement caused by motion and transduce these signals into electrical impulses via excitatory synapses. Lateral lines serve an important role in schooling behavior, predation, and orientation. Fish can use their lateral line system to follow the vortices produced by fleeing prey. Lateral lines are usually visible as faint lines of pores running lengthwise down each side, from the vicinity of the gill covers to the base of the tail. In some species, the receptive organs of the lateral line have been modified to function as electroreceptors, which are organs used to detect electrical impulses, and as such, these systems remain closely linked. Most amphibian larvae and some fully aquatic adult amphibians possess mechanosensitive systems comparable to the lateral line.

In physiology, a stimulus is a detectable change in the physical or chemical structure of an organism's internal or external environment. The ability of an organism or organ to detect external stimuli, so that an appropriate reaction can be made, is called sensitivity (excitability). Sensory receptors can receive information from outside the body, as in touch receptors found in the skin or light receptors in the eye, as well as from inside the body, as in chemoreceptors and mechanoreceptors. When a stimulus is detected by a sensory receptor, it can elicit a reflex via stimulus transduction. An internal stimulus is often the first component of a homeostatic control system. External stimuli are capable of producing systemic responses throughout the body, as in the fight-or-flight response. In order for a stimulus to be detected with high probability, its level of strength must exceed the absolute threshold; if a signal does reach threshold, the information is transmitted to the central nervous system (CNS), where it is integrated and a decision on how to react is made. Although stimuli commonly cause the body to respond, it is the CNS that finally determines whether a signal causes a reaction or not.

The supraoptic nucleus (SON) is a nucleus of magnocellular neurosecretory cells in the hypothalamus of the mammalian brain. The nucleus is situated at the base of the brain, adjacent to the optic chiasm. In humans, the SON contains about 3,000 neurons.

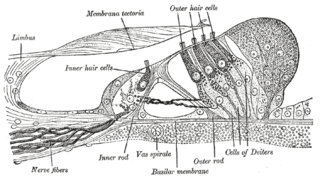

The auditory system is the sensory system for the sense of hearing. It includes both the sensory organs and the auditory parts of the sensory system.

Hair cells are the sensory receptors of both the auditory system and the vestibular system in the ears of all vertebrates, and in the lateral line organ of fishes. Through mechanotransduction, hair cells detect movement in their environment.

Range fractionation is a term used in biology to describe the way by which a group of sensory neurons are able to encode varying magnitudes of a stimulus. Sense organs are usually composed of many sensory receptors measuring the same property. These sensory receptors show a limited degree of precision due to an upper limit in firing rate. If the receptors are endowed with distinct transfer functions in such a way that the points of highest sensitivity are scattered along the axis of the quality being measured, the precision of the sense organ as a whole can be increased.

The superior olivary complex (SOC) or superior olive is a collection of brainstem nuclei that functions in multiple aspects of hearing and is an important component of the ascending and descending auditory pathways of the auditory system. The SOC is intimately related to the trapezoid body: most of the cell groups of the SOC are dorsal to this axon bundle while a number of cell groups are embedded in the trapezoid body. Overall, the SOC displays a significant interspecies variation, being largest in bats and rodents and smaller in primates.

The mismatch negativity (MMN) or mismatch field (MMF) is a component of the event-related potential (ERP) to an odd stimulus in a sequence of stimuli. It arises from electrical activity in the brain and is studied within the field of cognitive neuroscience and psychology. It can occur in any sensory system, but has most frequently been studied for hearing and for vision, in which case it is abbreviated to vMMN. The (v)MMN occurs after an infrequent change in a repetitive sequence of stimuli For example, a rare deviant (d) stimulus can be interspersed among a series of frequent standard (s) stimuli. In hearing, a deviant sound can differ from the standards in one or more perceptual features such as pitch, duration, loudness, or location. The MMN can be elicited regardless of whether someone is paying attention to the sequence. During auditory sequences, a person can be reading or watching a silent subtitled movie, yet still show a clear MMN. In the case of visual stimuli, the MMN occurs after an infrequent change in a repetitive sequence of images.

A topographic map is the ordered projection of a sensory surface, like the retina or the skin, or an effector system, like the musculature, to one or more structures of the central nervous system. Topographic maps can be found in all sensory systems and in many motor systems.

Parvalbumin (PV) is a calcium-binding protein with low molecular weight. In humans, it is encoded by the PVALB gene. It is not a member of the albumin family; it is named for its size and its ability to coagulate.

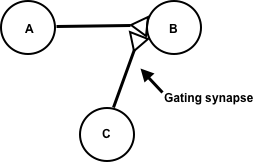

Synaptic gating is the ability of neural circuits to gate inputs by either suppressing or facilitating specific synaptic activity. Selective inhibition of certain synapses has been studied thoroughly, and recent studies have supported the existence of permissively gated synaptic transmission. In general, synaptic gating involves a mechanism of central control over neuronal output. It includes a sort of gatekeeper neuron, which has the ability to influence transmission of information to selected targets independently of the parts of the synapse upon which it exerts its action.

Recurrent thalamo-cortical resonance is an observed phenomenon of oscillatory neural activity between the thalamus and various cortical regions of the brain. It is proposed by Rodolfo Llinas and others as a theory for the integration of sensory information into the whole of perception in the brain. Thalamocortical oscillation is proposed to be a mechanism of synchronization between different cortical regions of the brain, a process known as temporal binding. This is possible through the existence of thalamocortical networks, groupings of thalamic and cortical cells that exhibit oscillatory properties.

The gustatory nucleus is the rostral part of the solitary nucleus located in the medulla. The gustatory nucleus is associated with the sense of taste and has two sections, the rostral and lateral regions. A close association between the gustatory nucleus and visceral information exists for this function in the gustatory system, assisting in homeostasis - via the identification of food that might be possibly poisonous or harmful for the body. There are many gustatory nuclei in the brain stem. Each of these nuclei corresponds to three cranial nerves, the facial nerve (VII), the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), and the vagus nerve (X) and GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter involved in its functionality. All visceral afferents in the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves first arrive in the nucleus of the solitary tract and information from the gustatory system can then be relayed to the thalamus and cortex.

The olivocochlear system is a component of the auditory system involved with the descending control of the cochlea. Its nerve fibres, the olivocochlear bundle (OCB), form part of the vestibulocochlear nerve, and project from the superior olivary complex in the brainstem (pons) to the cochlea.

An organism is said to be sexually dimorphic when male and female conspecifics have anatomical differences in features such as body size, coloration, or ornamentation, but disregarding differences of reproductive organs. Sexual dimorphism is usually a product of sexual selection, with female choice leading to elaborate male ornamentation and male-male competition leading to the development of competitive weaponry. However, evolutionary selection also acts on the sensory systems that receivers use to perceive external stimuli. If the benefits of perception to one sex or the other are different, sex differences in sensory systems can arise. For example, female production of signals used to attract mates can put selective pressure on males to improve their ability to detect those signals. As a result, only males of this species will evolve specialized mechanisms to aid in detection of the female signal. This article uses examples of sex differences in the olfactory, visual, and auditory systems of various organisms to show how sex differences in sensory systems arise when it benefits one sex and not the other to have enhanced perception of certain external stimuli. In each case, the form of the sex difference reflects the function it serves in terms of enhanced reproductive success.

The jamming avoidance response is a behavior of some species of weakly electric fish. It occurs when two electric fish with wave discharges meet – if their discharge frequencies are very similar, each fish shifts its discharge frequency to increase the difference between the two. By doing this, both fish prevent jamming of their sense of electroreception.

Feature detection is a process by which the nervous system sorts or filters complex natural stimuli in order to extract behaviorally relevant cues that have a high probability of being associated with important objects or organisms in their environment, as opposed to irrelevant background or noise.

Conspecific song preference is the ability songbirds require to distinguish conspecific song from heterospecific song in order for females to choose an appropriate mate, and for juvenile males to choose an appropriate song tutor during vocal learning. Researchers studying the swamp sparrow have demonstrated that young birds are born with this ability, because juvenile males raised in acoustic isolation and tutored with artificial recordings choose to learn only songs that contain their own species' syllables. Studies conducted at later life stages indicate that conspecific song preference is further refined and strengthened throughout development as a function of social experience. The selective response properties of neurons in the songbird auditory pathway has been proposed as the mechanism responsible for both the innate and acquired components of this preference.

Many experiments have been done to find out how the brain interprets stimuli and how animals develop fear responses. The emotion, fear, has been hard-wired into almost every individual, due to its vital role in the survival of the individual. Researchers have found that fear is established unconsciously and that the amygdala is involved with fear conditioning.

References

- ↑ Fay, R.R.; Edds-Walton, P.L (2001). "Bimodal Units in the Torus Semicircularis of the Toadfish (Opsanus tau)". Biological Bulletin. 201 (2): 280–281. doi:10.2307/1543366. JSTOR 1543366. PMID 11687424.

- ↑ Carr, C.E.; Maler, L.; Heiligenberg, W.; Sas, E. (20 December 1981). "Laminar organization of the afferent and efferent systems of the torus semicircularis of gymnotiform fish: morphological substrates for parallel processing in the electrosensory system". Journal of Comparative Neurology. 203 (4): 649–670. doi:10.1002/cne.902030406. PMID 7035506. S2CID 37088993.

- ↑ Penna, Mario; Lin, Wen-Yu; Feng, Albert S. (28 November 2001). "Temporal selectivity by single neurons in the torus semicircularis of Batrachyla antartandica (Amphibia: Leptodactylidae)". Journal of Comparative Physiology. 187 (11): 901–912. doi:10.1007/s00359-001-0263-9. PMID 11866188. S2CID 20115979.

- ↑ Mangiamele, Lisa A.; Burmeister, Sabrina S. (2011). "Auditory selectivity for acoustic features that confer species recognition in the túngara frog" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology. 214 (17): 2911–2918. doi: 10.1242/jeb.058362 . PMID 21832134 . Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ↑ Belekhova, M.G.; Kenigfest, N.B.; Karamian, O.A. (2004). "Distribution of Calcium-Binding Proteins in the Central and Peripheral Regions of the Turtle Mesencephalic Center Torus Semicircularis". Doklady Biological Sciences. 399 (4): 451–454. doi:10.1007/s10630-005-0009-x. PMID 15717605. S2CID 1560882.