A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a synapse. The cell receiving the signal, or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

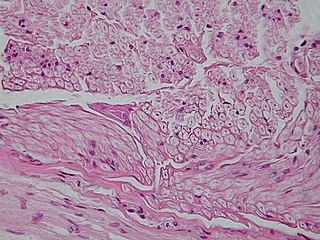

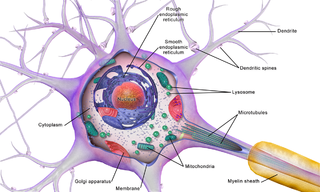

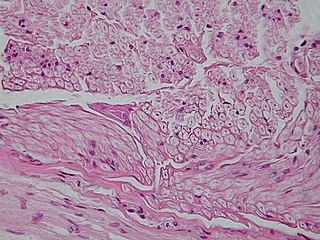

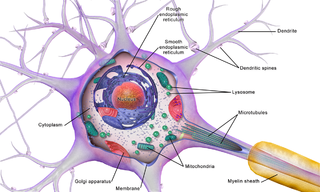

Nervous tissue, also called neural tissue, is the main tissue component of the nervous system. The nervous system regulates and controls body functions and activity. It consists of two parts: the central nervous system (CNS) comprising the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system (PNS) comprising the branching peripheral nerves. It is composed of neurons, also known as nerve cells, which receive and transmit impulses, and neuroglia, also known as glial cells or glia, which assist the propagation of the nerve impulse as well as provide nutrients to the neurons.

In neuroscience, synaptic plasticity is the ability of synapses to strengthen or weaken over time, in response to increases or decreases in their activity. Since memories are postulated to be represented by vastly interconnected neural circuits in the brain, synaptic plasticity is one of the important neurochemical foundations of learning and memory.

Glia, also called glial cells (gliocytes) or neuroglia, are non-neuronal cells in the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system that do not produce electrical impulses. The neuroglia make up more than one half the volume of neural tissue in the human body. They maintain homeostasis, form myelin in the peripheral nervous system, and provide support and protection for neurons. In the central nervous system, glial cells include oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, ependymal cells and microglia, and in the peripheral nervous system they include Schwann cells and satellite cells.

Astrocytes, also known collectively as astroglia, are characteristic star-shaped glial cells in the brain and spinal cord. They perform many functions, including biochemical control of endothelial cells that form the blood–brain barrier, provision of nutrients to the nervous tissue, maintenance of extracellular ion balance, regulation of cerebral blood flow, and a role in the repair and scarring process of the brain and spinal cord following infection and traumatic injuries. The proportion of astrocytes in the brain is not well defined; depending on the counting technique used, studies have found that the astrocyte proportion varies by region and ranges from 20% to around 40% of all glia. Another study reports that astrocytes are the most numerous cell type in the brain. Astrocytes are the major source of cholesterol in the central nervous system. Apolipoprotein E transports cholesterol from astrocytes to neurons and other glial cells, regulating cell signaling in the brain. Astrocytes in humans are more than twenty times larger than in rodent brains, and make contact with more than ten times the number of synapses.

Synaptogenesis is the formation of synapses between neurons in the nervous system. Although it occurs throughout a healthy person's lifespan, an explosion of synapse formation occurs during early brain development, known as exuberant synaptogenesis. Synaptogenesis is particularly important during an individual's critical period, during which there is a certain degree of synaptic pruning due to competition for neural growth factors by neurons and synapses. Processes that are not used, or inhibited during their critical period will fail to develop normally later on in life.

Glutamate receptors are synaptic and non synaptic receptors located primarily on the membranes of neuronal and glial cells. Glutamate is abundant in the human body, but particularly in the nervous system and especially prominent in the human brain where it is the body's most prominent neurotransmitter, the brain's main excitatory neurotransmitter, and also the precursor for GABA, the brain's main inhibitory neurotransmitter. Glutamate receptors are responsible for the glutamate-mediated postsynaptic excitation of neural cells, and are important for neural communication, memory formation, learning, and regulation.

The neuroimmune system is a system of structures and processes involving the biochemical and electrophysiological interactions between the nervous system and immune system which protect neurons from pathogens. It serves to protect neurons against disease by maintaining selectively permeable barriers, mediating neuroinflammation and wound healing in damaged neurons, and mobilizing host defenses against pathogens.

Glutamate transporters are a family of neurotransmitter transporter proteins that move glutamate – the principal excitatory neurotransmitter – across a membrane. The family of glutamate transporters is composed of two primary subclasses: the excitatory amino acid transporter (EAAT) family and vesicular glutamate transporter (VGLUT) family. In the brain, EAATs remove glutamate from the synaptic cleft and extrasynaptic sites via glutamate reuptake into glial cells and neurons, while VGLUTs move glutamate from the cell cytoplasm into synaptic vesicles. Glutamate transporters also transport aspartate and are present in virtually all peripheral tissues, including the heart, liver, testes, and bone. They exhibit stereoselectivity for L-glutamate but transport both L-aspartate and D-aspartate.

Neuromodulation is the physiological process by which a given neuron uses one or more chemicals to regulate diverse populations of neurons. Neuromodulators typically bind to metabotropic, G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) to initiate a second messenger signaling cascade that induces a broad, long-lasting signal. This modulation can last for hundreds of milliseconds to several minutes. Some of the effects of neuromodulators include: altering intrinsic firing activity, increasing or decreasing voltage-dependent currents, altering synaptic efficacy, increasing bursting activity and reconfigurating synaptic connectivity.

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that permits a neuron to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or to the target effector cell.

The subgranular zone (SGZ) is a brain region in the hippocampus where adult neurogenesis occurs. The other major site of adult neurogenesis is the subventricular zone (SVZ) in the brain.

Gliotransmitters are chemicals released from glial cells that facilitate neuronal communication between neurons and other glial cells. They are usually induced from Ca2+ signaling, although recent research has questioned the role of Ca2+ in gliotransmitters and may require a revision of the relevance of gliotransmitters in neuronal signalling in general.

In neurophysiology, a dendritic spike refers to an action potential generated in the dendrite of a neuron. Dendrites are branched extensions of a neuron. They receive electrical signals emitted from projecting neurons and transfer these signals to the cell body, or soma. Dendritic signaling has traditionally been viewed as a passive mode of electrical signaling. Unlike its axon counterpart which can generate signals through action potentials, dendrites were believed to only have the ability to propagate electrical signals by physical means: changes in conductance, length, cross sectional area, etc. However, the existence of dendritic spikes was proposed and demonstrated by W. Alden Spencer, Eric Kandel, Rodolfo Llinás and coworkers in the 1960s and a large body of evidence now makes it clear that dendrites are active neuronal structures. Dendrites contain voltage-gated ion channels giving them the ability to generate action potentials. Dendritic spikes have been recorded in numerous types of neurons in the brain and are thought to have great implications in neuronal communication, memory, and learning. They are one of the major factors in long-term potentiation.

Nonsynaptic plasticity is a form of neuroplasticity that involves modification of ion channel function in the axon, dendrites, and cell body that results in specific changes in the integration of excitatory postsynaptic potentials and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials. Nonsynaptic plasticity is a modification of the intrinsic excitability of the neuron. It interacts with synaptic plasticity, but it is considered a separate entity from synaptic plasticity. Intrinsic modification of the electrical properties of neurons plays a role in many aspects of plasticity from homeostatic plasticity to learning and memory itself. Nonsynaptic plasticity affects synaptic integration, subthreshold propagation, spike generation, and other fundamental mechanisms of neurons at the cellular level. These individual neuronal alterations can result in changes in higher brain function, especially learning and memory. However, as an emerging field in neuroscience, much of the knowledge about nonsynaptic plasticity is uncertain and still requires further investigation to better define its role in brain function and behavior.

Stephen J Smith is Meritorious Investigator at the Allen Institute for Brain Science [1] and Emeritus Professor of Molecular and Cellular Physiology at Stanford University [2]. He held faculty and Howard Hughes Medical Institute positions at the Yale University School of Medicine 1980-1989. He served 1990-2014 as a Stanford Professor, teaching many courses in synaptic physiology and cellular microscopy while mentoring many students and fellows [3]. He also taught in many expert workshops and summer courses at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory and the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Communication between neurons happens primarily through chemical neurotransmission at the synapse. Neurotransmitters are packaged into synaptic vesicles for release from the presynaptic cell into the synapse, from where they diffuse and can bind to postsynaptic receptors. While most presynaptic cells are historically thought to release one vesicle at a time per active site, more recent research has pointed towards the possibility of multiple vesicles being released from the same active site in response to an action potential.

Vladimir Parpura, MD, PhD (b.1964) is a Croatian-American neurobiologist who is currently a professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and an elected fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Alexei Verkhratsky, sometimes spelled Alexej, is a professor of neurophysiology at the University of Manchester best known for his research on the physiology and pathophysiology of neuroglia, calcium signalling, and brain ageing. He is an elected member and vice-president of Academia Europaea, of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina, of the Real Academia Nacional de Farmacia (Spain), of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, of Polish Academy of Sciences, and Dana Alliance for Brain Initiatives, among others. Since 2010, he is a Ikerbasque Research Professor and from 2012 he is deputy director of the Achucarro Basque Center for Neuroscience in Bilbao. He is a distinguished professor at Jinan University, China Medical University of Shenyang, and Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine and is an editor-in-chief of Cell Calcium, receiving editor for Cell Death and Disease, and Acta Physiologica and member of editorial board of many academic journals.

Brain cells make up the functional tissue of the brain. The rest of the brain tissue is structural or connective called the stroma which includes blood vessels. The two main types of cells in the brain are neurons, also known as nerve cells, and glial cells, also known as neuroglia.