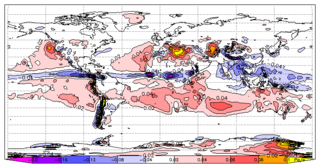

The Tropical Atlantic Variability (TAV) is influenced by internal interaction and external effects. TAV can be discussed in different time scales: seasonal (annual cycle) and interannual.

The Tropical Atlantic Variability (TAV) is influenced by internal interaction and external effects. TAV can be discussed in different time scales: seasonal (annual cycle) and interannual.

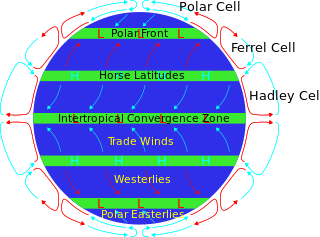

Seasonal variability is the dominant time scale of TAV, which is due to the seasonal march of the Sun. [1] This seasonal variability is related to the movement of Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which is the convergent zone of trade winds from south and north near the equator. It has strong vertical convection resulting to a redundant participation band and weak winds. The mean location of the ITCZ over the Atlantic Ocean is 5–10 degrees north of the geographical equator. [2] [3] All this asymmetric of ITCZ is the ultimate cause of the annual cycle in equatorial sea surface temperature (SST) in Atlantic by maintaining southerly cross-equatorial winds that intensify in boreal summer/fall and relax in boreal spring. [4] [5] From March to April, during which the temperature of the equator reaches maximum, winds are weakest and the sun shines directly over the equator. So, SST is uniformly warm near the equator, which makes the ITCZ really sensitive to even small disturbance of SST and explains the relaxation of cross-equator winds in spring. From July to September, during which the temperature of the equator reaches its minimum, ITCZ reaches its northernmost location, which explains the intensification of cross-equator winds. It can be seen that the process of cooling takes 3 months while that of warming takes 7 months, which are asymmetric. This seasonal asymmetry is due to influence of seasonal continental monsoon. Because of the narrow width of Atlantic, continental monsoon has a much more important influence on its variation compared to the wide Pacific Ocean, whose leading factor is air-sea interaction.

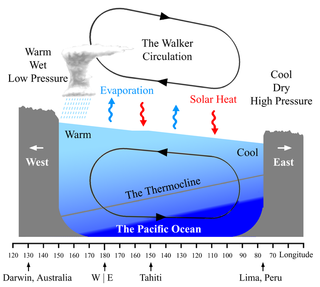

For interannual, there is one mode called Atlantic Niño, of which periodicity varies. During the Atlantic Nino event, eastern area of Atlantic will appear warm SST anomalies accompanying a relaxation of trade winds. [6] This mechanism, which is known as Bjerknes feedback, [7] is similar to El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

"On interannual and longer timescales, no single mode seems to dominate. Instead, several mechanisms are responsible for tropical Atlantic variability. On the equator, both observational and modeling studies indicate that there is a Bjerknes-type air–sea coupled mode arising from the interaction of the equatorial zonal SST gradient, ITCZ convection, zonal wind, and thermocline depth." [1]

The horse latitudes are the latitudes about 30 degrees north and south of the Equator. They are characterized by sunny skies, calm winds, and very little precipitation. They are also known as subtropical ridges or highs. It is a high-pressure area at the divergence of trade winds and the westerlies.

Upwelling is an oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water from deep water towards the ocean surface. It replaces the warmer and usually nutrient-depleted surface water. The nutrient-rich upwelled water stimulates the growth and reproduction of primary producers such as phytoplankton. The biomass of phytoplankton and the presence of cool water in those regions allow upwelling zones to be identified by cool sea surface temperatures (SST) and high concentrations of chlorophyll a.

El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a global climate phenomenon that emerges from variations in winds and sea surface temperatures over the tropical Pacific Ocean. Those variations have an irregular pattern but do have some semblance of cycles. The occurrence of ENSO is not predictable. It affects the climate of much of the tropics and subtropics, and has links (teleconnections) to higher-latitude regions of the world. The warming phase of the sea surface temperature is known as "El Niño" and the cooling phase as "La Niña". The Southern Oscillation is the accompanying atmospheric oscillation, which is coupled with the sea temperature change.

The Intertropical Convergence Zone, known by sailors as the doldrums or the calms because of its monotonous windless weather, is the area where the northeast and the southeast trade winds converge. It encircles Earth near the thermal equator though its specific position varies seasonally. When it lies near the geographic equator, it is called the near-equatorial trough. Where the ITCZ is drawn into and merges with a monsoonal circulation, it is sometimes referred to as a monsoon trough.

The Tropical Ocean Global Atmosphere program (TOGA) was a ten-year study (1985–1994) of the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP), aimed specifically at the prediction of climate phenomena on time scales of months to years.

The Pacific decadal oscillation (PDO) is a robust, recurring pattern of ocean-atmosphere climate variability centered over the mid-latitude Pacific basin. The PDO is detected as warm or cool surface waters in the Pacific Ocean, north of 20°N. Over the past century, the amplitude of this climate pattern has varied irregularly at interannual-to-interdecadal time scales. There is evidence of reversals in the prevailing polarity of the oscillation occurring around 1925, 1947, and 1977; the last two reversals corresponded with dramatic shifts in salmon production regimes in the North Pacific Ocean. This climate pattern also affects coastal sea and continental surface air temperatures from Alaska to California.

The Walker circulation, also known as the Walker cell, is a conceptual model of the air flow in the tropics in the lower atmosphere (troposphere). According to this model, parcels of air follow a closed circulation in the zonal and vertical directions. This circulation, which is roughly consistent with observations, is caused by differences in heat distribution between ocean and land. In addition to motions in the zonal and vertical direction the tropical atmosphere also has considerable motion in the meridional direction as part of, for example, the Hadley Circulation.

The Madden–Julian oscillation (MJO) is the largest element of the intraseasonal variability in the tropical atmosphere. It was discovered in 1971 by Roland Madden and Paul Julian of the American National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). It is a large-scale coupling between atmospheric circulation and tropical deep atmospheric convection. Unlike a standing pattern like the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), the Madden–Julian oscillation is a traveling pattern that propagates eastward, at approximately 4 to 8 m/s, through the atmosphere above the warm parts of the Indian and Pacific oceans. This overall circulation pattern manifests itself most clearly as anomalous rainfall.

The North Equatorial Current (NEC) is a westward wind-driven current mostly located near the equator, but the location varies from different oceans. The NEC in the Pacific and the Atlantic is about 5°-20°N, while the NEC in the Indian Ocean is very close to the equator. It ranges from the sea surface down to 400 m in the western Pacific.

The Equatorial Counter Current is an eastward flowing, wind-driven current which extends to depths of 100–150 metres (330–490 ft) in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans. More often called the North Equatorial Countercurrent (NECC), this current flows west-to-east at about 3-10°N in the Atlantic, Indian Ocean and Pacific basins, between the North Equatorial Current (NEC) and the South Equatorial Current (SEC). The NECC is not to be confused with the Equatorial Undercurrent (EUC) that flows eastward along the equator at depths around 200 metres (660 ft) in the western Pacific rising to 100 metres (330 ft) in the eastern Pacific.

The geography of South America contains many diverse regions and climates. Geographically, South America is generally considered a continent forming the southern portion of the landmass of the Americas, south and east of the Colombia–Panama border by most authorities, or south and east of the Panama Canal by some. South and North America are sometimes considered a single continent or supercontinent, while constituent regions are infrequently considered subcontinents.

The Hadley cell, also known as the Hadley circulation, is a global-scale tropical atmospheric circulation that features air rising near the equator, flowing poleward near the tropopause at a height of 12–15 km (7.5–9.3 mi) above the Earth's surface, cooling and descending in the subtropics at around 25 degrees latitude, and then returning equatorward near the surface. It is a thermally direct circulation within the troposphere that emerges due to differences in insolation and heating between the tropics and the subtropics. On a yearly average, the circulation is characterized by a circulation cell on each side of the equator. The Southern Hemisphere Hadley cell is slightly stronger on average than its northern counterpart, extending slightly beyond the equator into the Northern Hemisphere. During the summer and winter months, the Hadley circulation is dominated by a single, cross-equatorial cell with air rising in the summer hemisphere and sinking in the winter hemisphere. Analogous circulations may occur in extraterrestrial atmospheres, such as on Venus and Mars.

Tropical cyclogenesis is the development and strengthening of a tropical cyclone in the atmosphere. The mechanisms through which tropical cyclogenesis occur are distinctly different from those through which temperate cyclogenesis occurs. Tropical cyclogenesis involves the development of a warm-core cyclone, due to significant convection in a favorable atmospheric environment.

The Atlantic Equatorial Mode or Atlantic Niño is a quasiperiodic interannual climate pattern of the equatorial Atlantic Ocean. It is the dominant mode of year-to-year variability that results in alternating warming and cooling episodes of sea surface temperatures accompanied by changes in atmospheric circulation. The term Atlantic Niño comes from its close similarity with the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) that dominates the tropical Pacific basin. For this reason, the Atlantic Niño is often called the little brother of El Niño. The Atlantic Niño usually appears in northern summer, and is not the same as the Atlantic Meridional (Interhemispheric) Mode that consists of a north-south dipole across the equator and operates more during northern spring. The equatorial warming and cooling events associated with the Atlantic Niño are known to be strongly related to rainfall variability over the surrounding continents, especially in West African countries bordering the Gulf of Guinea. Therefore, understanding of the Atlantic Niño has important implications for climate prediction in those regions. Although the Atlantic Niño is an intrinsic mode to the equatorial Atlantic, there may be a tenuous causal relationship between ENSO and the Atlantic Niño in some circumstances.

The Tropical Atlantic SST Dipole refers to a cross-equatorial sea surface temperature (SST) pattern that appears dominant on decadal timescales. It has a period of about 12 years, with the SST anomalies manifesting their most pronounced features around 10–15 degrees of latitude off of the Equator. It is also referred to as the interhemispheric SST gradient or the Meridional Atlantic mode.

There are a number of explanations of the asymmetry of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), known by sailors as the Doldrums.

Pacific Meridional Mode (PMM) is a climate mode in the North Pacific. In its positive state, it is characterized by the coupling of weaker trade winds in the northeast Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Baja California with decreased evaporation over the ocean, thus increasing sea surface temperatures (SST); and the reverse during its negative state. This coupling develops during the winter months and spreads southwestward towards the equator and the central and western Pacific during spring, until it reaches the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which tends to shift north in response to a positive PMM.

The Angola - Benguela front (ABF) is a permanent frontal feature situated between 15° and 17°S off the coast of Angola and Namibia, west Africa. It separates the saline, warm and nutrient-poor sea water of the Angola Current from the cold and nutrient-rich sea water associated with the Benguela Current.

Ocean dynamical thermostat is a physical mechanism through which changes in the mean radiative forcing influence the gradients of sea surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean and the strength of the Walker circulation. Increased radiative forcing (warming) is more effective in the western Pacific than in the eastern where the upwelling of cold water masses damps the temperature change. This increases the east-west temperature gradient and strengthens the Walker circulation. Decreased radiative forcing (cooling) has the opposite effect.

The recharge oscillator model for El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a theory described for the first time in 1997 by Jin., which explains the periodical variation of the sea surface temperature (SST) and thermocline depth that occurs in the central equatorial Pacific Ocean. The physical mechanisms at the basis of this oscillation are periodical recharges and discharges of the zonal mean equatorial heat content, due to ocean-atmosphere interaction. Other theories have been proposed to model ENSO, such as the delayed oscillator, the western Pacific oscillator and the advective reflective oscillator. A unified and consistent model has been proposed by Wang in 2001, in which the recharge oscillator model is included as a particular case.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)