A pilus is a hair-like cell-surface appendage found on many bacteria and archaea. The terms pilus and fimbria can be used interchangeably, although some researchers reserve the term pilus for the appendage required for bacterial conjugation. All conjugative pili are primarily composed of pilin – fibrous proteins, which are oligomeric.

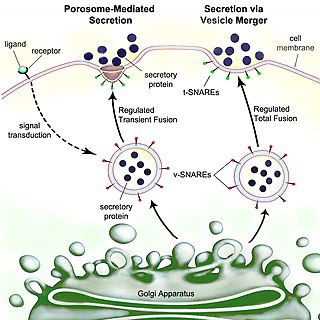

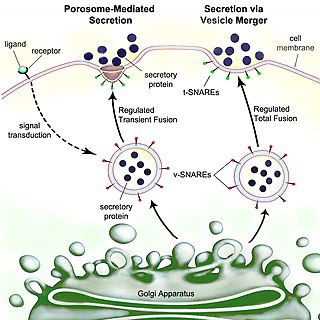

Secretion is the movement of material from one point to another, such as a secreted chemical substance from a cell or gland. In contrast, excretion is the removal of certain substances or waste products from a cell or organism. The classical mechanism of cell secretion is via secretory portals at the plasma membrane called porosomes. Porosomes are permanent cup-shaped lipoprotein structures embedded in the cell membrane, where secretory vesicles transiently dock and fuse to release intra-vesicular contents from the cell.

A tumour inducing (Ti) plasmid is a plasmid found in pathogenic species of Agrobacterium, including A. tumefaciens, A. rhizogenes, A. rubi and A. vitis.

The bacterial outer membrane is found in gram-negative bacteria. Gram-negative bacteria form two lipid bilayers in their cell envelopes - an inner membrane (IM) that encapsulates the cytoplasm, and an outer membrane (OM) that encapsulates the periplasm.

Pilin refers to a class of fibrous proteins that are found in pilus structures in bacteria. These structures can be used for the exchange of genetic material, or as a cell adhesion mechanism. Although not all bacteria have pili or fimbriae, bacterial pathogens often use their fimbriae to attach to host cells. In Gram-negative bacteria, where pili are more common, individual pilin molecules are linked by noncovalent protein-protein interactions, while Gram-positive bacteria often have polymerized LPXTG pilin.

The gene rpoS encodes the sigma factor sigma-38, a 37.8 kD protein in Escherichia coli. Sigma factors are proteins that regulate transcription in bacteria. Sigma factors can be activated in response to different environmental conditions. rpoS is transcribed in late exponential phase, and RpoS is the primary regulator of stationary phase genes. RpoS is a central regulator of the general stress response and operates in both a retroactive and a proactive manner: it not only allows the cell to survive environmental challenges, but it also prepares the cell for subsequent stresses (cross-protection). The transcriptional regulator CsgD is central to biofilm formation, controlling the expression of the curli structural and export proteins, and the diguanylate cyclase, adrA, which indirectly activates cellulose production. The rpoS gene most likely originated in the gammaproteobacteria.

The twin-arginine translocation pathway is a protein export, or secretion pathway found in plants, bacteria, and archaea. In contrast to the Sec pathway which transports proteins in an unfolded manner, the Tat pathway serves to actively translocate folded proteins across a lipid membrane bilayer. In plants, the Tat translocase is located in the thylakoid membrane of the chloroplast, where it acts to export proteins into the thylakoid lumen. In bacteria, the Tat translocase is found in the cytoplasmic membrane and serves to export proteins to the cell envelope, or to the extracellular space. The existence of a Tat translocase in plant mitochondria is also proposed.

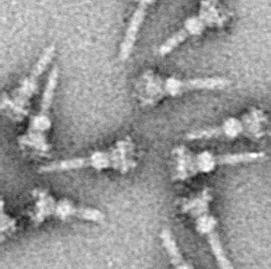

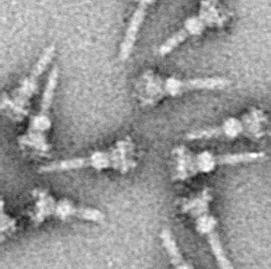

The type III secretion system is one of the bacterial secretion systems used by bacteria to secrete their effector proteins into the host's cells to promote virulence and colonisation. While the type III secretion system has been widely regarded as equivalent to the injectisome, many argue that the injectisome is only part of the type III secretion system, which also include structures like the flagellar export apparatus. The T3SS is a needle-like protein complex found in several species of pathogenic gram-negative bacteria.

In molecular biology, trimeric autotransporter adhesins (TAAs), are proteins found on the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. Bacteria use TAAs in order to infect their host cells via a process called cell adhesion. TAAs also go by another name, oligomeric coiled-coil adhesins, which is shortened to OCAs. In essence, they are virulence factors, factors that make the bacteria harmful and infective to the host organism.

Chaperone-usher fimbriae (CU) are linear, unbranching, outer-membrane pili secreted by gram-negative bacteria through the chaperone-usher system rather than through type IV secretion or extracellular nucleation systems. These fimbriae are built up out of modular pilus subunits, which are transported into the periplasm in a Sec dependent manner. Chaperone-usher secreted fimbriae are important pathogenicity factors facilitating host colonisation, localisation and biofilm formation in clinically important species such as uropathogenic Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Gabriel Waksman FMedSci, FRS, is Courtauld professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at University College London (UCL), and professor of structural and molecular biology at Birkbeck College, University of London. He is the director of the Institute of Structural and Molecular Biology (ISMB) at UCL and Birkbeck, head of the Department of Structural and Molecular Biology at UCL, and head of the Department of Biological Sciences at Birkbeck.

The type VI secretion system (T6SS) is one of the bacterial secretion systems, membrane protein complexes, used by a wide range of gram-negative bacteria to transport effectors. Effectors are moved from the interior of a bacterial cell, across the membrane into an adjacent target cell. While often reported that the T6SS was discovered in 2006 by researchers studying the causative agent of cholera, Vibrio cholerae, the first study demonstrating that T6SS genes encode a protein export apparatus was actually published in 2004, in a study of protein secretion by the fish pathogen Edwardsiella tarda.

The type 2 secretion system is a type of protein secretion machinery found in various species of Gram-negative bacteria, including many human pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Vibrio cholerae. The type II secretion system is one of six protein secretory systems commonly found in Gram-negative bacteria, along with the type I, type III, and type IV secretion systems, as well as the chaperone/usher pathway, the autotransporter pathway/type V secretion system, and the type VI secretion system. Like these other systems, the type II secretion system enables the transport of cytoplasmic proteins across the lipid bilayers that make up the cell membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. Secretion of proteins and effector molecules out of the cell plays a critical role in signaling other cells and in the invasion and parasitism of host cells.

Twitching motility is a form of crawling bacterial motility used to move over surfaces. Twitching is mediated by the activity of hair-like filaments called type IV pili which extend from the cell's exterior, bind to surrounding solid substrates, and retract, pulling the cell forwards in a manner similar to the action of a grappling hook. The name twitching motility is derived from the characteristic jerky and irregular motions of individual cells when viewed under the microscope. It has been observed in many bacterial species, but is most well studied in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Myxococcus xanthus. Active movement mediated by the twitching system has been shown to be an important component of the pathogenic mechanisms of several species.

CsgD is a transcription and response regulator protein referenced to as the master modulator of bacterial biofilm development. In E. coli cells, CsgD is tasked with aiding the transition from planktonic cell motility to the stationary phase of biofilm formation, in response to environmental growth factors. A transcription analysis assay illustrated a heightened decrease in CsgD's DNA-binding capacity when phosphorylated at A.A. D59 of the protein's primary sequence. Therefore, in the protein's active form (unphosphorylated), CsgD is capable of carrying out its normal functions of regulating curli proteins (fimbria) and producing ECM polysaccharides (cellulose). Following a promoter-lacZ fusion assay of CsgD binding to specific target sites on E. coli's genome, two classes of binding targets were identified: group I genes and group II genes. The group I genes, akin to fliE and yhbT, exhibit repressed transcription following their interaction with CsgD, whilst group II genes, including yccT and adrA, illustrated active functionality. Other group I operons that illustrate repressed transcription include fliE and fliEFGH, for motile flagellum formation. Other group II genes, imperative to the transition towards stationary biofilm development, include csgBA, encoding for curli fimbriae, and adrA, encoding for the synthesis of cyclic diguanylate. In this context, c-di-GMP functions as a bacterial secondary messenger, enhancing the production of extracellular cellulose and impeding flagellum production and rotation.

The Curli protein is a type of amyloid fiber produced by certain strains of enterobacteria. They are extracellular fibers located on bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella spp. These fibers serve to promote cell community behavior through biofilm formation in the extracellular matrix. Amyloids are associated with several human neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, Parkinson's disease, and prion diseases. The study of curli may help to understand human diseases thought to arise from improper amyloid fiber formation. The curli pili are generally assembled through the extracellular nucleation precipitation pathway.

Bacterial secretion systems are protein complexes present on the cell membranes of bacteria for secretion of substances. Specifically, they are the cellular devices used by pathogenic bacteria to secrete their virulence factors to invade the host cells. They can be classified into different types based on their specific structure, composition and activity. Generally, proteins can be secreted through two different processes. One process is a one-step mechanism in which proteins from the cytoplasm of bacteria are transported and delivered directly through the cell membrane into the host cell. Another involves a two-step activity in which the proteins are first transported out of the inner cell membrane, then deposited in the periplasm, and finally through the outer cell membrane into the host cell.

The bacterial type IV secretion system, also known as the type IV secretion system or the T4SS, is a secretion protein complex found in gram negative bacteria, gram positive bacteria, and archaea. It is able to transport proteins and DNA across the cell membrane. The type IV secretion system is just one of many bacterial secretion systems. Type IV secretion systems are related to conjugation machinery which generally involve a single-step secretion system and the use of a pilus. Type IV secretion systems are used for conjugation, DNA exchange with the extracellular space, and for delivering proteins to target cells. The type IV secretion system is divided into type IVA and type IVB based on genetic ancestry.

Parvulin-like peptidyl-prolyl isomerase (PrsA), also referred to as putative proteinase maturation protein A (PpmA), functions as a molecular chaperone in Gram-positive bacteria, such as B. subtilis, S. aureus, L. monocytogenes and S. pyogenes. PrsA proteins contain a highly conserved parvulin domain that contains peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase) activity capable of catalyzing the bond N-terminal to proline from cis to trans, or vice versa, which is a rate limiting step in protein folding. PrsA homologs also contain a foldase domain suspected to aid in the folding of proteins but, unlike the parvulin domain, is not highly conserved. PrsA proteins are capable of forming multimers in vivo and in vitro and, when dimerized, form a claw-like structure linked by the NC domains. Most Gram-positive bacteria contain only one PrsA-like protein, but some organisms such as L. monocytogenes, B. anthracis and S. pyogenes contain two PrsAs.

Type VII secretion systems are bacterial secretion systems first observed in the phyla Actinomycetota and Bacillota. Bacteria use such systems to transport, or secrete, proteins into the environment. The bacterial genus Mycobacterium uses type VII secretion systems (T7SS) to secrete proteins across their cell envelope. The first T7SS system discovered was the ESX-1 System.