Related Research Articles

The history of Uganda comprises the history of the people who inhabited the territory of present-day Uganda before the establishment of the Republic of Uganda, and the history of that country once it was established. Evidence from the Paleolithic era shows humans have inhabited Uganda for at least 50,000 years. The forests of Uganda were gradually cleared for agriculture by people who probably spoke Central Sudanic languages.

Apollo Milton Obote was a Ugandan political leader who led Uganda to independence from British colonial rule in 1962. Following the nation's independence, he served as prime minister of Uganda from 1962 to 1966 and the second president of Uganda from 1966 to 1971, then again from 1980 to 1985.

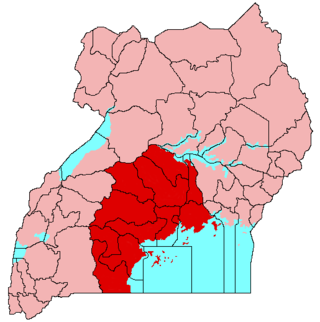

Buganda is a Bantu kingdom within Uganda. The kingdom of the Baganda people, Buganda is the largest of the traditional kingdoms in present-day East Africa, consisting of Buganda's Central Region, including the Ugandan capital Kampala. The 14 million Baganda make up the largest Ugandan region, representing approximately 16% of Uganda's population.

The early history of Uganda comprises the history of Uganda before the territory that is today Uganda was made into a British protectorate at the end of the 19th century. Prior to this, the region was divided between several closely related kingdoms.

The Protectorate of Uganda was a protectorate of the British Empire from 1894 to 1962. In 1893 the Imperial British East Africa Company transferred its administration rights of territory consisting mainly of the Kingdom of Buganda to the British government.

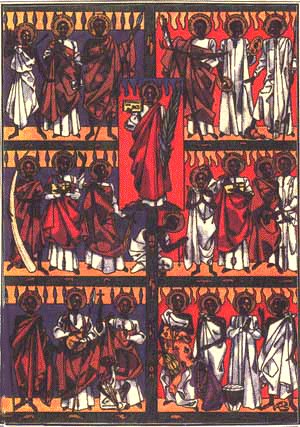

The Uganda Martyrs are a group of 22 Catholic and 23 Anglican converts to Christianity in the historical kingdom of Buganda, now part of Uganda, who were executed between 31 January 1885 and 27 January 1887.

Kabaka Yekka, commonly abbreviated as KY, was a monarchist political movement and party in Uganda. Kabaka Yekka means 'king only' in the Ganda language, Kabaka being the title of the King in the kingdom of Buganda.

The Constitution of Uganda is the supreme law of Uganda. The fourth and current constitution was promulgated on 8 October 1995. It sanctions a republican form of government with a powerful President.

The Buganda Crisis, also called the 1966 Mengo Crisis, the Kabaka Crisis, or the 1966 Crisis, domestically, was a period of political turmoil that occurred in Buganda. It was driven by conflict between Prime Minister Milton Obote and the Kabaka of Buganda, Mutesa II, culminating in a military assault upon the latter's residence that drove him into exile.

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, also known as the Central African Federation or CAF, was a colonial federation that consisted of three southern African territories: the self-governing British colony of Southern Rhodesia and the British protectorates of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. It existed between 1953 and 1963.

The history of Buganda is that of the Buganda kingdom of the Baganda people, the largest of the traditional kingdoms in present-day Uganda.

A non-sovereign monarchy or constituent monarchy is one in which the head of the monarchical polity, and the polity itself, are subject to a temporal authority higher than their own. The constituent states of the German Empire or the Princely States of British India provide historical examples; while the Zulu King, whose power derives from the Constitution of South Africa, is a contemporary one.

The Ganda people, or Baganda, are a Bantu ethnic group native to Buganda, a subnational kingdom within Uganda. Traditionally composed of 52 clans, the Baganda are the largest people of the Bantu ethnic group in Uganda, comprising 24.5 percent of the population at the time of the 2014 census.

The Uganda Legislative Council (LEGCO) was the predecessor of the Parliament of Uganda, prior to Uganda's independence from the United Kingdom. LEGCO was small to start with and all its members were Europeans. Its legislative powers were limited, since all important decisions came from the British Government in Whitehall.

The Hilton Young Commission was a Commission of Inquiry appointed in 1926 to look into the possible closer union of the British territories in East and Central Africa. These were individually economically underdeveloped, and it was suggested that some form of association would result both in cost savings and their more rapid development. The Commission recommended an administrative union of the East African mainland territories, possibly to be joined later by the Central African ones. It also proposed that the legislatures of each territory should continue and saw any form of self-government as being a long-term aspiration. It did however reject the possibility of the European minorities in Kenya or Northern Rhodesia establishing political control in those territories, and rejected the claim of Kenyan Asians for the same voting rights as Europeans. Although the commission's recommendations on an administrative union were not followed immediately, closer ties in East Africa were established in the 1940s. However, in Central Africa, its report had the effect of encouraging European settlers to seek closer association with Southern Rhodesia, in what became in 1953 the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

The lost counties referendum of November 1964 was a local referendum held to decide whether the "lost counties" of Buyaga and Bugangaizi in Uganda should continue to be part of the Kingdom of Buganda, be transferred back to the Kingdom of Bunyoro, or be established as a separate district. The electorate, consisting of the residents of the two counties at the time of independence, voted overwhelmingly to be returned to Bunyoro.

The Ugandan Constitutional Conference, held at Lancaster House in the autumn of 1961, was organised by the British Government to pave the way of Ugandan independence.

The Kabaka crisis was a political and constitutional crisis in the Uganda Protectorate between 1953 and 1955 wherein the Kabaka Mutesa II pressed for Bugandan secession from the Uganda Protectorate and was subsequently deposed and exiled by the British governor Andrew Cohen. Widespread discontent with this action forced the British government to backtrack, resulting in the restoration of Mutesa as specified in the Buganda Agreement of 1955, which ultimately shaped the nature of Ugandan independence.

Michael Kintu was a Ugandan politician who served as Katikkiro of the Kingdom of Buganda from 1955 to 1964.

Ugandan nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Uganda, as amended; the Uganda Citizenship and Immigration Control Act; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Uganda. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality describes the relationship of an individual to the state under international law, whereas citizenship is the domestic relationship of an individual within the nation. Commonwealth countries often use the terms nationality and citizenship as synonyms, despite their legal distinction and the fact that they are regulated by different governmental administrative bodies. Ugandan nationality is typically obtained under the principal of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth to parents with Ugandan nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalisation or registration.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Onek C. Adyanga (25 May 2011). Modes of British Imperial Control of Africa: A Case Study of Uganda, c.1890-1990. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 137–139. ISBN 978-1-4438-3035-5.

- 1 2 Apter, David E. (1967). The Political Kingdom in Uganda: A Study in Bureaucratic Nationalism. Routledge. pp. 403, 488. ISBN 978-1-136-30757-7.

- ↑ Otunnu, Ogenga (26 December 2016). Crisis of Legitimacy and Political Violence in Uganda, 1890 to 1979. Springer. p. 150. ISBN 978-3-319-33156-0.

- 1 2 3 Mukholi, David (1995). A Complete Guide to Uganda's Fourth Constitution: History, Politics, and the Law. Fountain Publishers. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-9970-02-084-3.