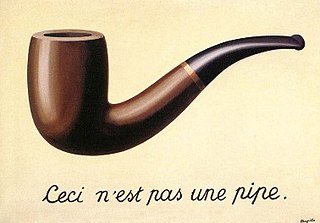

Surrealism is an art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike scenes and ideas. Its intention was, according to leader André Breton, to "resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality", or surreality. It produced works of painting, writing, theatre, filmmaking, photography, and other media as well.

Raymond Queneau was a French novelist, poet, critic, editor and co-founder and president of Oulipo, notable for his wit and cynical humour.

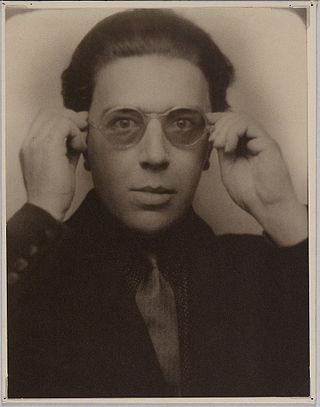

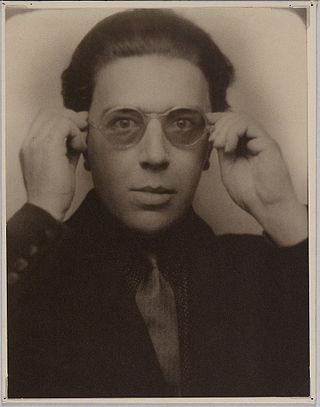

André Robert Breton was a French writer and poet, the co-founder, leader, and principal theorist of surrealism. His writings include the first Surrealist Manifesto of 1924, in which he defined surrealism as "pure psychic automatism".

André-Aimé-René Masson [andʁe aime ʁene masɔ̃] was a French artist.

The Surrealist Manifesto refers to several publications by Yvan Goll and André Breton, leaders of rival surrealist groups. Goll and Breton both published manifestos in October 1924 titled Manifeste du surréalisme. Breton wrote a second manifesto in 1929, which was published the following year, and in 1942, a reflection or a commentary on the potential for a third manifesto, exploring how the Surrealist movement might adapt to changing times.

Paul Nougé was a Belgian poet, founder and theoretician of surrealism in Belgium, sometimes known as the "Belgian Breton".

La Révolution surréaliste was a publication by the Surrealists in Paris. Twelve issues were published between 1924 and 1929.

Julien Michel Leiris was a French surrealist writer and ethnographer. Part of the Surrealist group in Paris, Leiris became a key member of the College of Sociology with Georges Bataille and head of research in ethnography at the CNRS.

Minotaure was a Surrealist-oriented magazine founded by Albert Skira and E. Tériade in Paris and published in French between 1933 and 1939. Minotaure published on the plastic arts, poetry, and literature, avant garde, as well as articles on esoteric and unusual aspects of literary and art history. Also included were psychoanalytical studies and artistic aspects of anthropology and ethnography. It was a lavish and extravagant magazine by the standards of the 1930s, profusely illustrated with high quality reproductions of art, often in color.

Documents was a Surrealist art magazine edited by Georges Bataille. Published in Paris from 1929 through 1930, it ran for 15 issues, each of which contained a wide range of original writing and photographs.

Jacques Baron (1905–1986) was a French surrealist poet whose first collection of poems was published in Aventure in 1921. Although he was initially involved with the Dada movement, he became a founding member of the Surrealist movement following his meeting with André Breton in 1921, and contributed to La Révolution surréaliste. In 1927, like many of his contemporaries, Baron joined the Cercle Communiste Démocratique. Although fascinated by dream-like states of the nomadic unconscious and other imaginary worlds of the "marvelous", a dispute with Breton in 1929 got him expelled from the movement, and prompted him to contribute to Un Cadavre, an anti-Breton pamphlet. After the break with Surrealism, Baron became associated with Georges Bataille and Documents, in which he published a short essay on "Crustaceans for the Critical Dictionary", an article on the sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, and a poem dedicated to Picasso, "Flames". He later collaborated on a number of reviews such as Le Voyage en Grèce, La Critique Sociale and Minotaure. Baron also wrote a novel, Charbon de mer (1935), a mémoire, L’An 1 du Surréalisme (1969), and a collection of poems, L’Allure poétique (1973).

Roger Vitrac was a French surrealist playwright and poet.

Jacques-André Boiffard was a French photographer, born in Épernon in Eure-et-Loir. He was a medical student in Paris until 1924 when he met André Breton through Pierre Naville, a Surrealist writer, and childhood friend.

Georges Alexandre Malkine was the only visual artist named in André Breton's 1924 Surrealist Manifesto among those who, at the time of its publication, had “performed acts of absolute surrealism." The rest Breton named were for the most part writers, including Louis Aragon, Robert Desnos, and Benjamin Peret. Malkine's 1926 painting Nuit D'amour was the precursor of the lyrical abstract school of painting.

Georges Limbour was a French writer, poet and art critic, and a regent of the Collège de 'Pataphysique.

Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution was a periodical issued by the Surrealist Group in Paris between 1930 and 1933. It was the successor of La Révolution surréaliste and preceded the primarily surrealist publication Minotaure.

Suzanne Muzard or Musard (1900–1992) was a French prostitute and photographer associated with surrealism. The lover of André Breton, she was addressed in Breton's love poems.

Émile Savitry (1903–1967) was a French photographer and painter.

Joseph Delteil was a 20th-century French writer and poet.

Jacques Hérold was a prominent surrealist painter born in Piatra Neamț, Romania.