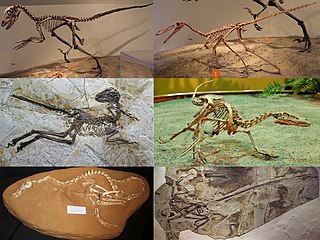

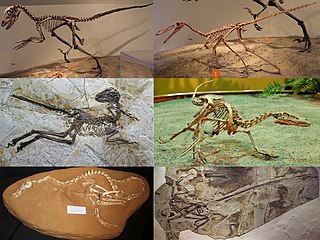

Archaeopteryx, sometimes referred to by its German name, "Urvogel" is a genus of bird-like dinosaurs. The name derives from the ancient Greek ἀρχαῖος (archaīos), meaning "ancient", and πτέρυξ (ptéryx), meaning "feather" or "wing". Between the late 19th century and the early 21st century, Archaeopteryx was generally accepted by palaeontologists and popular reference books as the oldest-known bird. Older potential avialans have since been identified, including Anchiornis, Xiaotingia, and Aurornis.

The screamers are three South American bird species placed in family Anhimidae. They were thought to be related to the Galliformes because of similar bills, but are more closely related to the family Anatidae, i.e. ducks and allies, and the magpie goose, within the clade Anseriformes. The clade is exceptional within the living birds in lacking uncinate processes of ribs. The three species are: The horned screamer ; the southern screamer or crested screamer ; and the northern screamer or black-necked screamer.

A transitional fossil is any fossilized remains of a life form that exhibits traits common to both an ancestral group and its derived descendant group. This is especially important where the descendant group is sharply differentiated by gross anatomy and mode of living from the ancestral group. These fossils serve as a reminder that taxonomic divisions are human constructs that have been imposed in hindsight on a continuum of variation. Because of the incompleteness of the fossil record, there is usually no way to know exactly how close a transitional fossil is to the point of divergence. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that transitional fossils are direct ancestors of more recent groups, though they are frequently used as models for such ancestors.

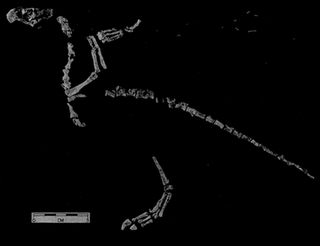

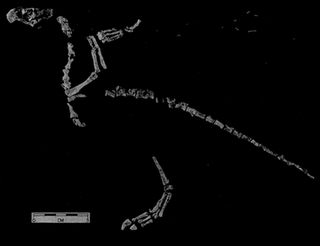

Compsognathus is a genus of small, bipedal, carnivorous theropod dinosaur. Members of its single species Compsognathus longipes could grow to around the size of a chicken. They lived about 150 million years ago, during the Tithonian age of the late Jurassic period, in what is now Europe. Paleontologists have found two well-preserved fossils, one in Germany in the 1850s and the second in France more than a century later. Today, C. longipes is the only recognized species, although the larger specimen discovered in France in the 1970s was once thought to belong to a separate species and named C. corallestris.

Dromaeosauridae is a family of feathered coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs. They were generally small to medium-sized feathered carnivores that flourished in the Cretaceous Period. The name Dromaeosauridae means 'running lizards', from Greek δρομαῖος (dromaîos), meaning 'running at full speed', 'swift', and σαῦρος (saûros), meaning 'lizard'. In informal usage, they are often called raptors, a term popularized by the film Jurassic Park; several genera include the term "raptor" directly in their name, and popular culture has come to emphasize their bird-like appearance and speculated bird-like behavior.

Protoavis is a problematic taxon known from fragmentary remains from Late Triassic Norian stage deposits near Post, Texas. The animal's true classification has been the subject of much controversy, and there are many different interpretations of what the taxon actually is. When it was first described, the fossils were described as being from a primitive bird which, if the identification is valid, would push back avian origins some 60-75 million years.

Coelurosauria is the clade containing all theropod dinosaurs more closely related to birds than to carnosaurs.

John Harold Ostrom was an American paleontologist who revolutionized the modern understanding of dinosaurs. Ostrom's work inspired what his pupil Robert T. Bakker has termed a "dinosaur renaissance".

Bird flight is the primary mode of locomotion used by most bird species in which birds take off and fly. Flight assists birds with feeding, breeding, avoiding predators, and migrating.

Avimimus, meaning "bird mimic", is a genus of oviraptorosaurian theropod dinosaur, named for its bird-like characteristics, that lived in the late Cretaceous in what is now Mongolia, around 85 to 70 million years ago.

Bird anatomy, or the physiological structure of birds' bodies, shows many unique adaptations, mostly aiding flight. Birds have a light skeletal system and light but powerful musculature which, along with circulatory and respiratory systems capable of very high metabolic rates and oxygen supply, permit the bird to fly. The development of a beak has led to evolution of a specially adapted digestive system.

The physiology of dinosaurs has historically been a controversial subject, particularly their thermoregulation. Recently, many new lines of evidence have been brought to bear on dinosaur physiology generally, including not only metabolic systems and thermoregulation, but on respiratory and cardiovascular systems as well.

The scientific question of within which larger group of animals birds evolved has traditionally been called the "origin of birds". The present scientific consensus is that birds are a group of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs that originated during the Mesozoic Era.

Compsognathidae is a family of coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs. Compsognathids were small carnivores, generally conservative in form, hailing from the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods. The bird-like features of these species, along with other dinosaurs such as Archaeopteryx inspired the idea for the connection between dinosaur reptiles and modern-day avian species. Compsognathid fossils preserve diverse integument — skin impressions are known from four genera commonly placed in the group, Compsognathus, Sinosauropteryx, Sinocalliopteryx, and Juravenator. While the latter three show evidence of a covering of some of the earliest primitive feathers over much of the body, Juravenator and Compsognathus also show evidence of scales on the tail or hind legs. "Ubirajara jubatus", informally described in 2020, had elaborate integumentary structures on its back and shoulders superficially similar to the display feathers of a standardwing bird-of-paradise, and unlike any other non-avian dinosaur currently described.

Sapeornis is a monotypic genus of avialan dinosaurs which lived during the early Cretaceous period. Sapeornis contains only one species, Sapeornis chaoyangensis.

Around 350 BCE, Aristotle and other philosophers of the time attempted to explain the aerodynamics of avian flight. Even after the discovery of the ancestral bird Archaeopteryx which lived over 150 million years ago, debates still persist regarding the evolution of flight. There are three leading hypotheses pertaining to avian flight: Pouncing Proavis model, Cursorial model, and Arboreal model.

John Alan Feduccia is a paleornithologist specializing in the origins and phylogeny of birds. He is S. K. Heninger Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of North Carolina. Feduccia's authored works include three major books, The Age of Birds, The Origin and Evolution of Birds, and Riddle of the Feathered Dragons.

This glossary explains technical terms commonly employed in the description of dinosaur body fossils. Besides dinosaur-specific terms, it covers terms with wider usage, when these are of central importance in the study of dinosaurs or when their discussion in the context of dinosaurs is beneficial. The glossary does not cover ichnological and bone histological terms, nor does it cover measurements.

The Origin of Birds is an early synopsis of bird evolution written in 1926 by Gerhard Heilmann, a Danish artist and amateur zoologist. The book was born from a series of articles published between 1913 and 1916 in Danish, and although republished as a book it received mainly criticism from established scientists and got little attention within Denmark. The English edition of 1926, however, became highly influential at the time due to the breadth of evidence synthesized as well as the artwork used to support its arguments. It was considered the last word on the subject of bird evolution for several decades after its publication.

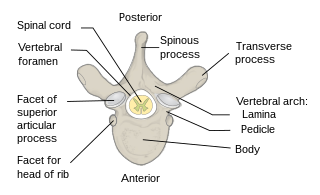

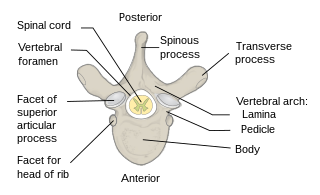

Each vertebra is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spinal segment and the particular species.