The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, often referred to as the Brady Act or the Brady Bill, is an Act of the United States Congress that mandated federal background checks on firearm purchasers in the United States, and imposed a five-day waiting period on purchases, until the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) was implemented in 1998. The act was appended to the end of Section 922 of title 18, United States Code. The intention of the act was to prevent persons with previous serious convictions from purchasing firearms.

The Domestic Violence Offender Gun Ban, often called the "Lautenberg Amendment", is an amendment to the Omnibus Consolidated Appropriations Act of 1997, enacted by the 104th United States Congress in 1996, which bans access to firearms by people convicted of crimes of domestic violence. The act is often referred to as "the Lautenberg Amendment" after its sponsor, Senator Frank Lautenberg. Lautenberg proposed the amendment after a decision from the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, involving underenforcement of domestic violence laws brought under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. President Bill Clinton signed the law as part of the Omnibus Appropriations Act of 1997.

The Gun Control Act of 1968 is a U.S. federal law that regulates the firearms industry and firearms ownership. Due to constitutional limitations, the Act is primarily based on regulating interstate commerce in firearms by generally prohibiting interstate firearms transfers except by manufacturers, dealers and importers licensed under a scheme set up under the Act.

Small v. United States, 544 U.S. 385 (2005), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States involving 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(1), which makes it illegal to possess a gun for individuals previously "convicted in any court" of crimes for which they could have been sentenced to more than one year in prison. The Court ruled, in a five to three decision, that "any court" does not include those in foreign countries. This decision resolved a circuit split on the issue, and reversed the lower ruling of the Third Circuit that the law did apply to foreign convictions.

The Firearm Owners' Protection Act (FOPA) of 1986 is a United States federal law that revised many provisions of the Gun Control Act of 1968.

The National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) is a background check system in the United States created by the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act of 1993 to prevent firearm sales to people prohibited under the Act. The system was launched by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 1998. Under the system, firearm dealers, manufacturers or importers who hold a Federal Firearms License (FFL) are required to undertake a NICS background check on prospective buyers before transferring a firearm. The NICS is not intended to be a gun registry, but is a list of persons prohibited from owning or possessing a firearm. By law, upon successfully passing the background check, the buyer’s details are to be discarded and a record on NICS of the firearm purchase is not to be made, though the seller as a FFL holder is required to keep a record of the transaction.

In the United States, the right to keep and bear arms is modulated by a variety of state and federal statutes. These laws generally regulate the manufacture, trade, possession, transfer, record keeping, transport, and destruction of firearms, ammunition, and firearms accessories. They are enforced by state, local and the federal agencies which include the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF).

The Armed Career Criminal Act of 1984 (ACCA) is a United States federal law that provides sentence enhancements for felons who commit crimes with firearms if they are convicted of certain crimes three or more times. Pennsylvania Senator Arlen Specter was a key proponent for the legislation.

Loss of rights due to criminal conviction refers to the practice in some countries of reducing the rights of individuals who have been convicted of a criminal offence. The restrictions are in addition to other penalties such as incarceration or fines. In addition to restrictions imposed directly upon conviction, there can also be collateral civil consequences resulting from a criminal conviction, but which are not imposed directly by the courts as a result of the conviction.

Gun laws in Utah regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition in the state of Utah in the United States.

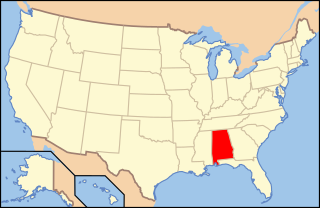

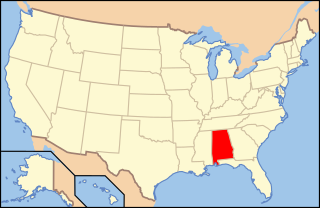

Gun laws in Alabama regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition in the state of Alabama in the United States.

United States v. Alfonso D. Lopez, Jr., 514 U.S. 549 (1995), was a landmark case of the United States Supreme Court that struck down the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990 (GFSZA) due to it being outside of Congress's power to regulate interstate commerce. It was the first case since 1937 in which the Court held that Congress had exceeded its power under the Commerce Clause.

Gun laws in Illinois regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition in the state of Illinois in the United States.

Gun laws in Indiana regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition in the U.S. state of Indiana. Laws and regulations are subject to change.

Gun laws in Michigan regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition in the U.S. state of Michigan.

Gun laws in North Carolina regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition in the U.S. state of North Carolina.

Gun laws in Pennsylvania regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in the United States.

Gun laws in Texas regulate the sale, possession, and use of firearms and ammunition in the U.S. state of Texas.

Abramski v. United States, 573 U.S. 169 (2014), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court found that making arrangements for a straw purchase of a gun is in violation of the Gun Control Act of 1968, and is different from re-selling or gifting a previously purchased gun. In the Abramski case, a former police officer from Virginia took advantage of a local discount to buy a gun for his uncle and later transferred it to Pennsylvania—the uncle's residence—using the appropriate federal procedure. During the purchase, Abramski falsely declared that he was purchasing the gun for himself.

The boyfriend loophole is a gap in American gun legislation that allows physically abusive ex-romantic partners and stalkers with previous convictions or restraining orders to access guns. While individuals who have been convicted of, or are under a restraining order for, domestic violence are prohibited from owning a firearm, the prohibition only applies if the victim was the perpetrator's spouse or cohabitant, or if the perpetrator had a child with the victim.