Phrack is an e-zine written by and for hackers, first published November 17, 1985. Described by Fyodor as "the best, and by far the longest running hacker zine," the magazine is open for contributions by anyone who desires to publish remarkable works or express original ideas on the topics of interest. It has a wide circulation which includes both hackers and computer security professionals.

Kevin David Mitnick is an American computer security consultant, author, and convicted hacker. He is best known for his high-profile 1995 arrest and five years in prison for various computer and communications-related crimes.

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986 (CFAA) is a United States cybersecurity bill that was enacted in 1986 as an amendment to existing computer fraud law, which had been included in the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984. The law prohibits accessing a computer without authorization, or in excess of authorization. Prior to computer-specific criminal laws, computer crimes were prosecuted as mail and wire fraud, but the applying law was often insufficient.

Operation Sundevil was a 1990 nationwide United States Secret Service crackdown on "illegal computer hacking activities." It involved raids in approximately fifteen different cities and resulted in three arrests and the confiscation of computers, the contents of electronic bulletin board systems (BBSes), and floppy disks. It was revealed in a press release on May 9, 1990. The arrests and subsequent court cases resulted in the creation of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. The operation is now seen as largely a public-relations stunt. Operation Sundevil has also been viewed as one of the preliminary attacks on the Legion of Doom and similar hacking groups. The raid on Steve Jackson Games, which led to the court case Steve Jackson Games, Inc. v. United States Secret Service, is often attributed to Operation Sundevil, but the Electronic Frontier Foundation states that it is unrelated and cites this attribution as a media error.

Melvin Reynolds is an American politician from Illinois. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in the United States House of Representatives from 1993 to 1995. He resigned in October 1995 after a jury convicted him of sexual assault charges related to sex with an underage campaign worker.

Craig Neidorf, a.k.a.Knight Lightning, was one of the two founding editors of Phrack Magazine, an online, text-based ezine that defined the hacker mentality of the mid 1980s.

Jeremy Hammond is an American activist and computer hacker from Chicago. He founded the computer security training website HackThisSite in 2003. He was first imprisoned over the Protest Warrior hack in 2005 and was later convicted of computer fraud in 2013 for hacking the private intelligence firm Stratfor and releasing data to WikiLeaks, and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

The Computer Underground Digest (CuD) was a weekly online newsletter on early Internet cultural, social, and legal issues published by Gordon Meyer and Jim Thomas from March 1990 to March 2000.

United States v. Drew, 259 F.R.D. 449, was an American federal criminal case in which the U.S. government charged Lori Drew with violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) over her alleged cyberbullying of her 13-year-old neighbor, Megan Meier, who had committed suicide. The jury deadlocked on a felony conspiracy count and acquitted Drew of three felony CFAA violations, but found her guilty of lesser included misdemeanor violations; the judge overturned these convictions in response to a subsequent motion for acquittal by Drew.

Leonard Rose, aka Terminus, is an American hacker who in 1991 accepted a plea bargain that convicted him of two counts of wire fraud stemming from publishing an article in Phrack magazine.

Albert Gonzalez is an American computer hacker and computer criminal who is accused of masterminding the combined credit card theft and subsequent reselling of more than 170 million card and ATM numbers from 2005 to 2007: the biggest such fraud in history. Gonzalez and his accomplices used SQL injection to deploy backdoors on several corporate systems in order to launch packet sniffing attacks which allowed him to steal computer data from internal corporate networks. During his spree, he was said to have thrown himself a $75,000 birthday party and complained about having to count $340,000 by hand after his currency-counting machine broke. Gonzalez stayed at lavish hotels but his formal homes were modest.

Andrew Alan Escher Auernheimer, best known by his pseudonym weev, is an American computer hacker and self-avowed Internet troll. Affiliated with the alt-right, the Southern Poverty Law Center has described him as being a neo-Nazi, white supremacist, and antisemitic conspiracy theorist. He has used many aliases in contacting the media, although most sources indicate his real first name as Andrew.

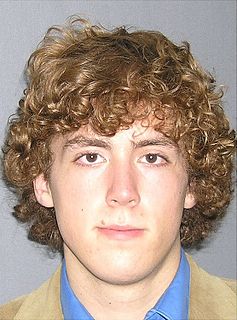

The Sarah Palin email hack occurred on September 16, 2008, during the 2008 United States presidential election campaign when vice presidential candidate, Sarah Palin's, Yahoo! personal email account was subjected to unauthorized access. The hacker, David Kernell, obtained access to Palin's account by looking up biographical details, such as her high school and birthdate, and using Yahoo!'s account recovery for forgotten passwords. Kernell then posted several pages of Palin's email on 4chan's /b/ board. Kernell, who at the time of the offense was a 20-year-old college student, was the son of longtime Democratic state representative Mike Kernell of Memphis.

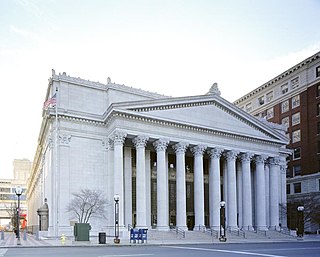

United States v. Ivanov was an American court case addressing subject-matter jurisdiction for computer crimes performed by Internet users outside of the United States against American businesses and infrastructure. In trial court, Aleksey Vladimirovich Ivanov of Chelyabinsk, Russia was indicted for conspiracy, computer fraud, extortion, and possession of illegal access devices; all crimes committed against the Online Information Bureau (OIB) whose business and infrastructure were based in Vernon, Connecticut.

Vladislav Anatolievich Horohorin,, alias BadB, is a former hacker and international credit card trafficker who was convicted of wire fraud and served a seven-year prison sentence.

United States v. Kane, No 11-mj-00001, is a court case where a software bug in a video poker machine was exploited to win several hundred thousand dollars. Central to the case was whether a video poker machine constituted a protected computer and whether the exploitation of a software bug constituted exceeding authorized access under Title 18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(4) of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA). Ultimately, the Court ruled that the government’s argument failed to sufficiently meet the “exceeding authorized access” requirement of Title 18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(4) and granted the Defendants’ Motions to Dismiss.

Maksim Viktorovich Yakubets is a Russian computer expert and alleged computer hacker. He is alleged to have been a member of the Evil Corp, Jabber Zeus Crew, as well as the alleged leader of the Bulgat malware conspiracy. Russian media openly describe Yakubets as a "hacker who stole $100 million", friend of Dmitry Peskov and discussed his lavish lifestyle, including luxury wedding with a daughter of FSB officer Eduard Bendersky and Lamborghini with "ВОР" registration plate. Yakubets impunity in Russia is perceived as clue of his close ties with FSB, but also criticized by domestic information security experts such as Ilya Sachkov.

Sandworm also known as Unit 74455, is allegedly a Russian cybermilitary unit of the GRU, the organization in charge of Russian military intelligence. Other names, given by cybersecurity researchers, include Telebots, Voodoo Bear, and Iron Viking.

United States v. Elizabeth A. Holmes, et al., is an ongoing United States federal criminal fraud case against the founder of now-defunct corporation Theranos, Elizabeth Holmes, and its former president and COO, Ramesh Balwani. The case alleged that Holmes and Balwani perpetrated multi-million dollar wire-fraud schemes against investors and patients. Holmes and Balwani each had their own jury trial.