The Toltec culture was a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture that ruled a state centered in Tula, Hidalgo, Mexico, during the Epiclassic and the early Post-Classic period of Mesoamerican chronology, reaching prominence from 950 to 1150 CE. The later Aztec culture considered the Toltec to be their intellectual and cultural predecessors and described Toltec culture emanating from Tōllān as the epitome of civilization. In the Nahuatl language the word Tōltēkatl (singular) or Tōltēkah (plural) came to take on the meaning "artisan". The Aztec oral and pictographic tradition also described the history of the Toltec Empire, giving lists of rulers and their exploits.

Chalchiuhtlicue is an Aztec deity of water, rivers, seas, streams, storms, and baptism. Chalchiuhtlicue is associated with fertility, and she is the patroness of childbirth. Chalchiuhtlicue was highly revered in Aztec culture at the time of the Spanish conquest, and she was an important deity figure in the Postclassic Aztec realm of central Mexico. Chalchiuhtlicue belongs to a larger group of Aztec rain gods, and she is closely related to another Aztec water god called Chalchiuhtlatonal.

Huitzilopochtli is the solar and war deity of sacrifice in Aztec religion. He was also the patron god of the Aztecs and their capital city, Tenochtitlan. He wielded Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent, as a weapon, thus also associating Huitzilopochtli with fire.

In Aztec mythology, Tonacatecuhtli was a creator and fertility god, worshipped for populating the earth and making it fruitful. Most Colonial-era manuscripts equate him with Ōmetēcuhtli. His consort was Tonacacihuatl.

In Aztec mythology, Xiuhtēcuhtli, was the god of fire, day and heat. In historical sources he is called by many names, which reflect his varied aspects and dwellings in the three parts of the cosmos. He was the lord of volcanoes, the personification of life after death, warmth in cold (fire), light in darkness and food during famine. He was also named Cuezaltzin ("flame") and Ixcozauhqui, and is sometimes considered to be the same as Huehueteotl, although Xiuhtecuhtli is usually shown as a young deity. His wife was Chalchiuhtlicue. Xiuhtecuhtli is sometimes considered to be a manifestation of Ometecuhtli, the Lord of Duality, and according to the Florentine Codex Xiuhtecuhtli was considered to be the father of the Gods, who dwelled in the turquoise enclosure in the center of earth. Xiuhtecuhtli-Huehueteotl was one of the oldest and most revered of the indigenous pantheon. The cult of the God of Fire, of the Year, and of Turquoise perhaps began as far back as the middle Preclassic period. Turquoise was the symbolic equivalent of fire for Aztec priests. A small fire was permanently kept alive at the sacred center of every Aztec home in honor of Xiuhtecuhtli.

The Maya calendar is a system of calendars used in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and in many modern communities in the Guatemalan highlands, Veracruz, Oaxaca and Chiapas, Mexico.

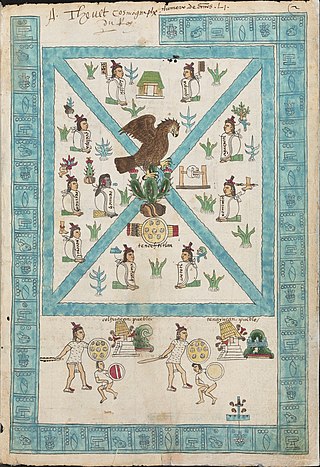

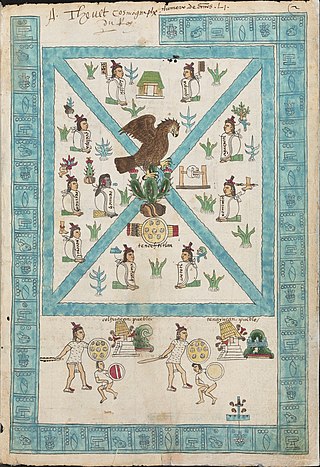

The Aztec or Mexica calendar is the calendrical system used by the Aztecs as well as other Pre-Columbian peoples of central Mexico. It is one of the Mesoamerican calendars, sharing the basic structure of calendars from throughout the region.

The calendrical systems devised and used by the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica, primarily a 260-day year, were used in religious observances and social rituals, such as divination.

Tlacaelel I was the principal architect of the Aztec Triple Alliance and hence the Mexica (Aztec) empire. He was the son of Emperor Huitzilihuitl and Queen Cacamacihuatl, nephew of Emperor Itzcoatl, father of poet Macuilxochitzin, and brother of Emperors Chimalpopoca and Moctezuma I.

The tōnalpōhualli, meaning "count of days" in Nahuatl, is a Mexica version of the 260-day calendar in use in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. This calendar is solar and consists of 20 13-day periods. Each trecena is ruled by a different deity. Graphic representations for the twenty day names have existed among certain ethnic, linguistic, or archaeologically identified peoples.

Diego Durán was a Dominican friar best known for his authorship of one of the earliest Western books on the history and culture of the Aztecs, The History of the Indies of New Spain, a book that was much criticised in his lifetime for helping the "heathen" maintain their culture.

The Aztec religion is a polytheistic and monistic pantheism in which the Nahua concept of teotl was construed as the supreme god Ometeotl, as well as a diverse pantheon of lesser gods and manifestations of nature. The popular religion tended to embrace the mythological and polytheistic aspects, and the Aztec Empire's state religion sponsored both the monism of the upper classes and the popular heterodoxies.

Aztec codices are Mesoamerican manuscripts made by the pre-Columbian Aztec, and their Nahuatl-speaking descendants during the colonial period in Mexico.

The Codex Borbonicus is an Aztec codex written by Aztec priests shortly before or after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. It is named after the Palais Bourbon in France and kept at the Bibliothèque de l'Assemblée Nationale in Paris. The codex is an outstanding example of how Aztec manuscript painting is crucial for the understanding of Mexica calendric constructions, deities, and ritual actions.

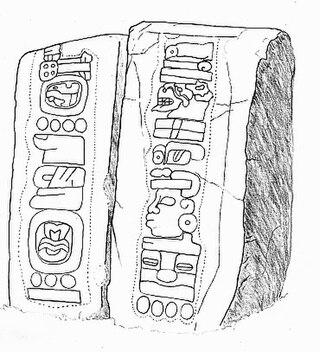

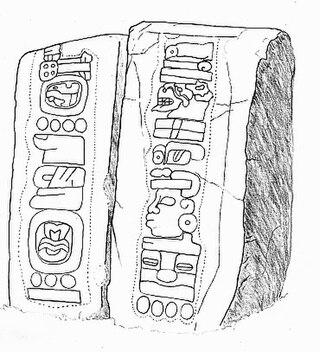

Mesoamerica, along with Mesopotamia and China, is one of three known places in the world where writing is thought to have developed independently. Mesoamerican scripts deciphered to date are a combination of logographic and syllabic systems. They are often called hieroglyphs due to the iconic shapes of many of the glyphs, a pattern superficially similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs. Fifteen distinct writing systems have been identified in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, many from a single inscription. The limits of archaeological dating methods make it difficult to establish which was the earliest and hence the progenitor from which the others developed. The best documented and deciphered Mesoamerican writing system, and the most widely known, is the classic Maya script. Earlier scripts with poorer and varying levels of decipherment include the Olmec hieroglyphs, the Zapotec script, and the Isthmian script, all of which date back to the 1st millennium BC. An extensive Mesoamerican literature has been conserved, partly in indigenous scripts and partly in postconquest transcriptions in the Latin script.

The xiuhpōhualli is a 365-day calendar used by the Aztecs and other pre-Columbian Nahua peoples in central Mexico. It is composed of eighteen 20-day "months," which through Spanish usage came to be known as veintenas, with an inauspicious, separate 5-day period at the end of the year called the nēmontēmi. The name given to the 20-day periods in pre-Columbian times is unknown, and though the Nahuatl word for moon or month, mētztli, is sometimes used today to describe them, the sixteenth-century missionary and ethnographer, Diego Durán explained that:

In ancient times the year was composed of eighteen months, and thus it was observed by these Indian people. Since their months were made of no more than twenty days, these were all the days contained in a month, because they were not guided by the moon but by the days; therefore, the year had eighteen months. The days of the year were counted twenty by twenty.

Toxcatl was the name of the fifth twenty-day month or "veintena" of the Aztec calendar which lasted approximately from the 5th to the 22nd May, and of the festival which was held every year in this month. The Festival of Toxcatl was dedicated to the god Tezcatlipoca and featured the sacrifice of a young man who had been impersonating the deity for a full year.

The Mexica New Year is the celebration of the new year according to the Aztec calendar. The date on which the holiday falls in the Gregorian calendar depends on the version of the calendar used, but it is generally considered to occur at sunrise on 12 March. The holiday is observed in some Nahua communities in Mexico. To celebrate, ocote (pitch-pine) candles are lit on the eve of the new year, along with fireworks, drumming, and singing. Some of the most important events occur in Huauchinango, Naupan, Mexico City, Zongolica, and Xicotepec.

In the Aztec (Mexica) culture, the Nahuatl word nēmontēmi refers to a period of five intercalary days inserted between the 360 days labeled with numbers and day-names in the main part of the Aztec seasonal calendar. Their location was roughly around 5–18 March every Gregorian year.

The Muisca calendar was a lunisolar calendar used by the Muisca. The calendar was composed of a complex combination of months and three types of years were used; rural years, holy years, and common years. Each month consisted of thirty days and the common year of twenty months, as twenty was the 'perfect' number of the Muisca, representing the total of extremeties; fingers and toes. The rural year usually contained twelve months, but one leap month was added. This month represented a month of rest. The holy year completed the full cycle with 37 months.