Related Research Articles

United States appellate procedure involves the rules and regulations for filing appeals in state courts and federal courts. The nature of an appeal can vary greatly depending on the type of case and the rules of the court in the jurisdiction where the case was prosecuted. There are many types of standard of review for appeals, such as de novo and abuse of discretion. However, most appeals begin when a party files a petition for review to a higher court for the purpose of overturning the lower court's decision.

In legal terminology, a complaint is any formal legal document that sets out the facts and legal reasons that the filing party or parties believes are sufficient to support a claim against the party or parties against whom the claim is brought that entitles the plaintiff(s) to a remedy. For example, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) that govern civil litigation in United States courts provide that a civil action is commenced with the filing or service of a pleading called a complaint. Civil court rules in states that have incorporated the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure use the same term for the same pleading.

A lawsuit is a proceeding by a party or parties against another in the civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today. The term "lawsuit" is used in reference to a civil action brought by a plaintiff demands a legal or equitable remedy from a court. The defendant is required to respond to the plaintiff's complaint. If the plaintiff is successful, judgment is in the plaintiff's favor, and a variety of court orders may be issued to enforce a right, award damages, or impose a temporary or permanent injunction to prevent an act or compel an act. A declaratory judgment may be issued to prevent future legal disputes.

In law, a summary judgment is a judgment entered by a court for one party and against another party summarily, i.e., without a full trial. Summary judgments may be issued on the merits of an entire case, or on discrete issues in that case. The formulation of the summary judgment standard is stated in somewhat different ways by courts in different jurisdictions. In the United States, the presiding judge generally must find there is "no genuine dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law." In England and Wales, the court rules for a party without a full trial when "the claim, defence or issue has no real prospect of success and there is no other compelling reason why the case or issue should be disposed of at a trial."

A demurrer is a pleading in a lawsuit that objects to or challenges a pleading filed by an opposing party. The word demur means "to object"; a demurrer is the document that makes the objection. Lawyers informally define a demurrer as a defendant saying "So what?" to the pleading.

In United States law, a motion is a procedural device to bring a limited, contested issue before a court for decision. It is a request to the judge to make a decision about the case. Motions may be made at any point in administrative, criminal or civil proceedings, although that right is regulated by court rules which vary from place to place. The party requesting the motion may be called the moving party, or may simply be the movant. The party opposing the motion is the nonmoving party or nonmovant.

Forum shopping is a colloquial term for the practice of litigants having their legal case heard in the court thought most likely to provide a favorable judgment. Some jurisdictions have, for example, become known as "plaintiff-friendly" and so have attracted litigation even when there is little or no connection between the legal issues and the jurisdiction in which they are to be litigated.

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure govern civil procedure in United States district courts. The FRCP are promulgated by the United States Supreme Court pursuant to the Rules Enabling Act, and then the United States Congress has seven months to veto the rules promulgated or they become part of the FRCP. The Court's modifications to the rules are usually based upon recommendations from the Judicial Conference of the United States, the federal judiciary's internal policy-making body.

A legal remedy, also referred to as judicial relief or a judicial remedy, is the means with which a court of law, usually in the exercise of civil law jurisdiction, enforces a right, imposes a penalty, or makes another court order to impose its will in order to compensate for the harm of a wrongful act inflicted upon an individual.

Default judgment is a binding judgment in favor of either party based on some failure to take action by the other party. Most often, it is a judgment in favor of a plaintiff when the defendant has not responded to a summons or has failed to appear before a court of law. The failure to take action is the default. The default judgment is the relief requested in the party's original petition.

In the United States, removal jurisdiction allows a defendant to move a civil action filed in a state court to the United States district court in the federal judicial district in which the state court is located. A federal statute governs removal.

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317 (1986), was a case decided by the United States Supreme Court, written by then-Associate Justice William Rehnquist. In Celotex, the Court held that a party moving for summary judgment need only show that the opposing party lacks evidence sufficient to support its case. A broader version of this doctrine was later formally added to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

A Doe subpoena is a subpoena that seeks the identity of an unknown defendant to a lawsuit. Most jurisdictions permit a plaintiff who does not yet know a defendant's identity to file suit against John Doe and then use the tools of the discovery process to seek the defendant's true name. A Doe subpoena is often served on an online service provider or ISP for the purpose of identifying the author of an anonymous post.

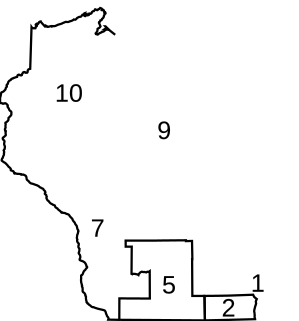

The Wisconsin circuit courts are the general trial courts in the state of Wisconsin. There are currently 69 circuits in the state, divided into 10 judicial administrative districts. Circuit court judges hear and decide both civil and criminal cases. Each of the 249 circuit court judges are elected and serve six-year terms.

The Virginia Circuit Courts are the state trial courts of general jurisdiction in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The Circuit Courts have jurisdiction to hear civil and criminal cases. For civil cases, the courts have authority to try cases with an amount in controversy of more than $4,500 and have exclusive original jurisdiction over claims for more than $25,000. In criminal matters, the Circuit Courts are the trial courts for all felony charges and for misdemeanors originally charged there. The Circuit Courts also have appellate jurisdiction for any case from the Virginia General District Courts claiming more than $50, which are tried de novo in the Circuit Courts.

Service of process in Virginia encompasses the set of rules indicating how a party to a lawsuit must be given service of process in the state of Virginia, in order for the judiciary of Virginia to have jurisdiction over that party. In the Virginia General District Court, the summons is referred to as either a "warrant" or as a "notice of motion for judgment" depending on the kind of case brought. In the Virginia Circuit Court it is simply called a summons.

Virginia civil procedure is the body of law that sets out the rules and standards that Virginia courts follow when adjudicating civil lawsuits. Professor W. Hamilton Bryson is the preeminent master and legal scholar on Virginia Civil Procedure. Many commentators particularly equate him with the "scholars and lords chancellors of old."

'Venue' in Virginia civil procedure describes the rules governing which court in the Commonwealth of Virginia is the appropriate place for a case to be tried, presuming that subject matter jurisdiction and personal jurisdiction have been established.

Lane v Holder is a civil lawsuit filed with the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia on behalf of plaintiff Michelle Lane, a resident of the District of Columbia, by the Second Amendment Foundation against Eric Holder, Attorney General for the United States, and W. Steven Flaherty, Superintendent of the Virginia State Police. The suit seeks to bar the Defendants from enforcing a provision of the Federal Gun Control Act of 1968 that prohibits the purchase of firearms by a non-resident of the state in which the purchase is made, and from enforcing a Virginia State statute prohibiting the sale of handguns, outright, to any non-resident of the State. The case was dismissed by the District Court judge Gerald Bruce Lee. An appeal by Lane and the SAF is pending before the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Karnoski v. Trump (2:17-cv-01297-MJP) is a lawsuit filed on August 29, 2017 in the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington. The suit, like the similar suits Jane Doe v. Trump, Stone v. Trump, and Stockman v. Trump, seeks to block Trump and top Pentagon officials from implementing the proposed ban on military service for transgender people under the auspices of the equal protection and due process clauses of the Fifth Amendment. The suit was filed on the behalf of three transgender plaintiffs, the Human Rights Campaign, and the Gender Justice League by Lambda Legal and OutServe-SLDN.

References

- ↑ "§ 16.1-77. Civil jurisdiction of general district courts; amending amount of claim".

- ↑ Va. Code Ann. § 16.1-77(3)

- ↑ Va. Code. Ann. §64.1–75.

- ↑ Va. Code. Ann. §8.01-261, −262.

- ↑ VA. Sup. Ct. R. 1.1 (2015).

- ↑ See, e.g., Commonwealth v. Fields, 88 Va. Cir. 151, 2014 Va. Cir. LEXIS 13 (Va. Cir. Ct. 2014).