The Easter Rising, also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an independent Irish Republic while the United Kingdom was fighting the First World War. It was the most significant uprising in Ireland since the rebellion of 1798 and the first armed conflict of the Irish revolutionary period. Sixteen of the Rising's leaders were executed from May 1916. The nature of the executions, and subsequent political developments, ultimately contributed to an increase in popular support for Irish independence.

Na Fianna Éireann, known as the Fianna, is an Irish nationalist youth organisation founded by Constance Markievicz in 1909, with later help from Bulmer Hobson. Fianna members were involved in setting up the Irish Volunteers, and had their own circle of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). They took part in the 1914 Howth gun-running and in the 1916 Easter Rising. They were active in the War of Independence and many took the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War.

The Irish Volunteers, sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force or Irish Volunteer Army, was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in response to the formation of its Irish unionist/loyalist counterpart the Ulster Volunteers in 1912, and its declared primary aim was "to secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to the whole people of Ireland". The Volunteers included members of the Gaelic League, Ancient Order of Hibernians and Sinn Féin, and, secretly, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Increasing rapidly to a strength of nearly 200,000 by mid-1914, it split in September of that year over John Redmond's commitment to the British war effort, with the smaller group retaining the name of "Irish Volunteers".

The Irish Citizen Army, or ICA, was a small paramilitary group of trained trade union volunteers from the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) established in Dublin for the defence of workers' demonstrations from the Dublin Metropolitan Police. It was formed by James Larkin, James Connolly and Jack White on 23 November 1913. Other prominent members included Seán O'Casey, Constance Markievicz, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, P. T. Daly and Kit Poole. In 1916, it took part in the Easter Rising, an armed insurrection aimed at ending British rule in Ireland.

Thomas Patrick Ashe was a member of the Gaelic League, the Gaelic Athletic Association, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and a founding member of the Irish Volunteers.

Diarmuid O'Hegarty was an Irish civil servant and revolutionary. O’Hegarty was a member of the Irish Volunteer executive, IRA director of communications, and director of Organisation. Diarmuid O’Hegarty was an extremely self- effacing man; he was described by Frank Pakenham as the ‘civil servant of the revolution’.

Michael Joseph Staines was an Irish republican, politician and police commissioner. He was born in Newport, County Mayo, his mother Margaret's home village, and where his father Edward was serving as a Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) officer.

Frongoch internment camp at Frongoch in Merionethshire, Wales was a makeshift place of imprisonment during the First World War and the 1916 Easter Rising.

Córas na Poblachta was a minor Irish republican political party founded in 1940.

Joseph O'Doherty was an Irish teacher, barrister, revolutionary, politician, county manager, member of the First Dáil and of the Irish Free State Seanad.

Richard "Dick" McKee was a prominent member of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). He was also friend to some senior members in the republican movement, including Éamon de Valera, Austin Stack and Michael Collins. Along with Peadar Clancy and Conor Clune, he was killed by his captors in Dublin Castle on Sunday, 21 November 1920, a day known as Bloody Sunday that also saw the killing of a network of British spies by the "Squad" unit of the Irish Republican Army and the killing of 14 people in Croke Park by the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC).

Gearóid O'Sullivan was an Irish teacher, Irish language scholar, army officer, barrister and Sinn Féin and Fine Gael politician.

Parnell Square is a Georgian square sited at the northern end of O'Connell Street in the city of Dublin, Ireland. It is in the city's D01 postal district.

Patrick Belton was an Irish nationalist, politician, farmer, and businessman. Closely associated with Michael Collins, he was active in the 1916 Easter Rising and in the Republican movement in the years that followed. Belton later provided a strong Catholic voice in an Irish nationalist context throughout his career. He was strongly anti-communist and he was a founder and leader of the Irish Christian Front. Supportive of Francisco Franco, Belton however opposed Eoin O'Duffy taking an Irish Brigade to Spain, feeling that they would be needed in Ireland to counter domestic "political ills".

County Wexford is a county located in the south-east of Ireland. The period 1916–1923 was one of the most turbulent in the county's history. In 1914 Ireland was still part of the United Kingdom. During World War I much war-related activity took place in County Wexford, especially in Wexford's coastal waters. A number of men enlisted in the British Army from Co. Wexford died in the land war in Europe. In 1916 Wexford Rebels seized the town of Enniscorthy during the Easter Rising. Co. Wexford was very active throughout the War of Independence and later fought an especially bloody Irish Civil War.

Gearóid Ó Cuinneagáin was an Irish language activist, nationalist and far-right politician born in Belfast, Ireland. He was the founder and leader of Ailtirí na hAiséirghe, a fascist party which sought to create a Christian corporatist state and revive the Irish language through the establishment of an authoritarian dictatorship in Ireland.

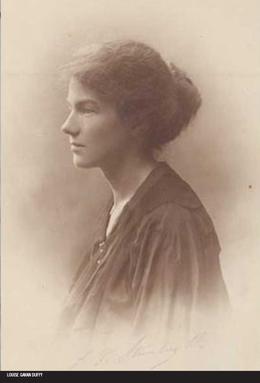

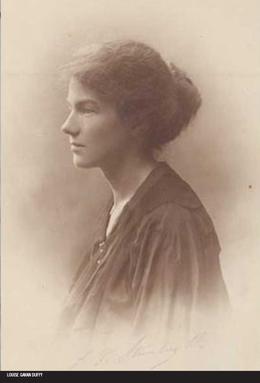

Louise Gavan Duffy was an educator, an Irish language enthusiast and a Gaelic revivalist, setting up the first Gaelscoil in Ireland. She was also a suffragist and Irish nationalist who was present in the General Post Office, the main headquarters during the 1916 Easter Rising.

Mary Josephine "Min" Ryan was an Irish Nationalist. A member of Cumann na mBan and the honorary secretary of the executive committee, she took part in the 1916 Easter Rising and the War of Independence.

Seán Mac Mahon was an Irish nationalist who fought in the 1916 rising.

Patrick MacGrath was born into an old Dublin republican family and took part in the 1916 Rising, as did two of his brothers. He was sent to Frongoch Internment Camp after the 1916 Rising and served his time there. He was a senior member of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), hunger striker, IRA Director of Operations and Training during its major bombing/sabotage in England and was the first of six IRA men executed by the Irish Government between 1940–1944. After participating in the Easter Rebellion, MacGrath remained in the IRA, rising in rank and becoming a major leader within the organisation.