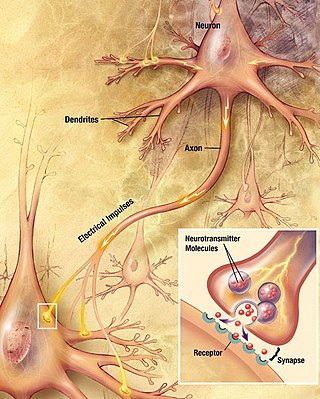

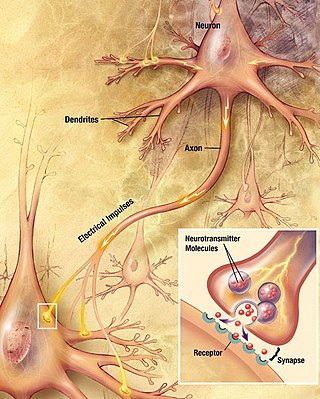

Within a nervous system, a neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network. Neurons communicate with other cells via synapses, which are specialized connections that commonly use minute amounts of chemical neurotransmitters to pass the electric signal from the presynaptic neuron to the target cell through the synaptic gap.

Chemical synapses are biological junctions through which neurons' signals can be sent to each other and to non-neuronal cells such as those in muscles or glands. Chemical synapses allow neurons to form circuits within the central nervous system. They are crucial to the biological computations that underlie perception and thought. They allow the nervous system to connect to and control other systems of the body.

In neuroscience, synaptic plasticity is the ability of synapses to strengthen or weaken over time, in response to increases or decreases in their activity. Since memories are postulated to be represented by vastly interconnected neural circuits in the brain, synaptic plasticity is one of the important neurochemical foundations of learning and memory.

An excitatory synapse is a synapse in which an action potential in a presynaptic neuron increases the probability of an action potential occurring in a postsynaptic cell. Neurons form networks through which nerve impulses travels, each neuron often making numerous connections with other cells of neurons. These electrical signals may be excitatory or inhibitory, and, if the total of excitatory influences exceeds that of the inhibitory influences, the neuron will generate a new action potential at its axon hillock, thus transmitting the information to yet another cell.

Retrograde signaling in biology is the process where a signal travels backwards from a target source to its original source. For example, the nucleus of a cell is the original source for creating signaling proteins. During retrograde signaling, instead of signals leaving the nucleus, they are sent to the nucleus. In cell biology, this type of signaling typically occurs between the mitochondria or chloroplast and the nucleus. Signaling molecules from the mitochondria or chloroplast act on the nucleus to affect nuclear gene expression. In this regard, the chloroplast or mitochondria act as a sensor for internal external stimuli which activate a signaling pathway.

Molecular neuroscience is a branch of neuroscience that observes concepts in molecular biology applied to the nervous systems of animals. The scope of this subject covers topics such as molecular neuroanatomy, mechanisms of molecular signaling in the nervous system, the effects of genetics and epigenetics on neuronal development, and the molecular basis for neuroplasticity and neurodegenerative diseases. As with molecular biology, molecular neuroscience is a relatively new field that is considerably dynamic.

Neurotransmission is the process by which signaling molecules called neurotransmitters are released by the axon terminal of a neuron, and bind to and react with the receptors on the dendrites of another neuron a short distance away. A similar process occurs in retrograde neurotransmission, where the dendrites of the postsynaptic neuron release retrograde neurotransmitters that signal through receptors that are located on the axon terminal of the presynaptic neuron, mainly at GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses.

Neural facilitation, also known as paired-pulse facilitation (PPF), is a phenomenon in neuroscience in which postsynaptic potentials (PSPs) evoked by an impulse are increased when that impulse closely follows a prior impulse. PPF is thus a form of short-term synaptic plasticity. The mechanisms underlying neural facilitation are exclusively pre-synaptic; broadly speaking, PPF arises due to increased presynaptic Ca2+

concentration leading to a greater release of neurotransmitter-containing synaptic vesicles. Neural facilitation may be involved in several neuronal tasks, including simple learning, information processing, and sound-source localization.

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that permits a neuron to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or to the target effector cell.

The Max Planck Institute of Experimental Medicine was a research institute of the Max Planck Society, located in Göttingen, Germany. On January 1, 2022, the institute merged with the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen to form the Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences.

In neuroscience, homeostatic plasticity refers to the capacity of neurons to regulate their own excitability relative to network activity. The term homeostatic plasticity derives from two opposing concepts: 'homeostatic' and plasticity, thus homeostatic plasticity means "staying the same through change". In the nervous system, neurons must be able to evolve with the development of their constantly changing environment while simultaneously staying the same amidst this change. This stability is important for neurons to maintain their activity and functionality to prevent neurons from carcinogenesis. At the same time, neurons need to have flexibility to adapt to changes and make connections to cope with the ever-changing environment of a developing nervous system.

Synaptic potential refers to the potential difference across the postsynaptic membrane that results from the action of neurotransmitters at a neuronal synapse. In other words, it is the “incoming” signal that a neuron receives. There are two forms of synaptic potential: excitatory and inhibitory. The type of potential produced depends on both the postsynaptic receptor, more specifically the changes in conductance of ion channels in the post synaptic membrane, and the nature of the released neurotransmitter. Excitatory post-synaptic potentials (EPSPs) depolarize the membrane and move the potential closer to the threshold for an action potential to be generated. Inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) hyperpolarize the membrane and move the potential farther away from the threshold, decreasing the likelihood of an action potential occurring. The Excitatory Post Synaptic potential is most likely going to be carried out by the neurotransmitters glutamate and acetylcholine, while the Inhibitory post synaptic potential will most likely be carried out by the neurotransmitters gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glycine. In order to depolarize a neuron enough to cause an action potential, there must be enough EPSPs to both depolarize the postsynaptic membrane from its resting membrane potential to its threshold and counterbalance the concurrent IPSPs that hyperpolarize the membrane. As an example, consider a neuron with a resting membrane potential of -70 mV (millivolts) and a threshold of -50 mV. It will need to be raised 20 mV in order to pass the threshold and fire an action potential. The neuron will account for all the many incoming excitatory and inhibitory signals via summative neural integration, and if the result is an increase of 20 mV or more, an action potential will occur.

Axon terminals are distal terminations of the branches of an axon. An axon, also called a nerve fiber, is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell that conducts electrical impulses called action potentials away from the neuron's cell body in order to transmit those impulses to other neurons, muscle cells or glands. In the central nervous system, most presynaptic terminals are actually formed along the axons, not at their ends.

Cellular neuroscience is a branch of neuroscience concerned with the study of neurons at a cellular level. This includes morphology and physiological properties of single neurons. Several techniques such as intracellular recording, patch-clamp, and voltage-clamp technique, pharmacology, confocal imaging, molecular biology, two photon laser scanning microscopy and Ca2+ imaging have been used to study activity at the cellular level. Cellular neuroscience examines the various types of neurons, the functions of different neurons, the influence of neurons upon each other, and how neurons work together.

Nonsynaptic plasticity is a form of neuroplasticity that involves modification of ion channel function in the axon, dendrites, and cell body that results in specific changes in the integration of excitatory postsynaptic potentials and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials. Nonsynaptic plasticity is a modification of the intrinsic excitability of the neuron. It interacts with synaptic plasticity, but it is considered a separate entity from synaptic plasticity. Intrinsic modification of the electrical properties of neurons plays a role in many aspects of plasticity from homeostatic plasticity to learning and memory itself. Nonsynaptic plasticity affects synaptic integration, subthreshold propagation, spike generation, and other fundamental mechanisms of neurons at the cellular level. These individual neuronal alterations can result in changes in higher brain function, especially learning and memory. However, as an emerging field in neuroscience, much of the knowledge about nonsynaptic plasticity is uncertain and still requires further investigation to better define its role in brain function and behavior.

Thomas Christian Südhof, ForMemRS, is a German-American biochemist known for his study of synaptic transmission. Currently, he is a professor in the school of medicine in the department of molecular and cellular physiology, and by courtesy in neurology, and in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University.

The active zone or synaptic active zone is a term first used by Couteaux and Pecot-Dechavassinein in 1970 to define the site of neurotransmitter release. Two neurons make near contact through structures called synapses allowing them to communicate with each other. As shown in the adjacent diagram, a synapse consists of the presynaptic bouton of one neuron which stores vesicles containing neurotransmitter, and a second, postsynaptic neuron which bears receptors for the neurotransmitter, together with a gap between the two called the synaptic cleft. When an action potential reaches the presynaptic bouton, the contents of the vesicles are released into the synaptic cleft and the released neurotransmitter travels across the cleft to the postsynaptic neuron and activates the receptors on the postsynaptic membrane.

In neuroscience, synaptic scaling is a form of homeostatic plasticity, in which the brain responds to chronically elevated activity in a neural circuit with negative feedback, allowing individual neurons to reduce their overall action potential firing rate. Where Hebbian plasticity mechanisms modify neural synaptic connections selectively, synaptic scaling normalizes all neural synaptic connections by decreasing the strength of each synapse by the same factor, so that the relative synaptic weighting of each synapse is preserved.

Neurotransmitters are released into a synapse in packaged vesicles called quanta. One quantum generates a miniature end plate potential (MEPP) which is the smallest amount of stimulation that one neuron can send to another neuron. Quantal release is the mechanism by which most traditional endogenous neurotransmitters are transmitted throughout the body. The aggregate sum of many MEPPs is an end plate potential (EPP). A normal end plate potential usually causes the postsynaptic neuron to reach its threshold of excitation and elicit an action potential. Electrical synapses do not use quantal neurotransmitter release and instead use gap junctions between neurons to send current flows between neurons. The goal of any synapse is to produce either an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) or an inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP), which generate or repress the expression, respectively, of an action potential in the postsynaptic neuron. It is estimated that an action potential will trigger the release of approximately 20% of an axon terminal's neurotransmitter load.

Communication between neurons happens primarily through chemical neurotransmission at the synapse. Neurotransmitters are packaged into synaptic vesicles for release from the presynaptic cell into the synapse, from where they diffuse and can bind to postsynaptic receptors. While most presynaptic cells are historically thought to release one vesicle at a time per active site, more recent research has pointed towards the possibility of multiple vesicles being released from the same active site in response to an action potential.