Space exploration is the use of astronomy and space technology to explore outer space. While the exploration of space is currently carried out mainly by astronomers with telescopes, its physical exploration is conducted both by uncrewed robotic space probes and human spaceflight. Space exploration, like its classical form astronomy, is one of the main sources for space science.

Luna 16 was an uncrewed 1970 space mission, part of the Soviet Luna program. It was the first robotic probe to land on the Moon and return a sample of lunar soil to Earth. The 101 grams sample was returned from Mare Fecunditatis. It represented the first successful lunar sample return mission by the Soviet Union and was the third lunar sample return mission overall.

In astronautics, the Hohmann transfer orbit is an orbital maneuver used to transfer a spacecraft between two orbits of different altitudes around a central body. For example, a Hohmann transfer could be used to raise a satellite's orbit from low Earth orbit to geostationary orbit. In the idealized case, the initial and target orbits are both circular and coplanar. The maneuver is accomplished by placing the craft into an elliptical transfer orbit that is tangential to both the initial and target orbits. The maneuver uses two impulsive engine burns: the first establishes the transfer orbit, and the second adjusts the orbit to match the target.

The Interplanetary Transport Network (ITN) is a collection of gravitationally determined pathways through the Solar System that require very little energy for an object to follow. The ITN makes particular use of Lagrange points as locations where trajectories through space can be redirected using little or no energy. These points have the peculiar property of allowing objects to orbit around them, despite lacking an object to orbit, as these points exist where gravitational forces between two celestial bodies are equal. While it would use little energy, transport along the network would take a long time.

Johann Gottfried Galle was a German astronomer from Radis, Germany, at the Berlin Observatory who, on 23 September 1846, with the assistance of student Heinrich Louis d'Arrest, was the first person to view the planet Neptune and know what he was looking at. Urbain Le Verrier had predicted the existence and position of Neptune, and sent the coordinates to Galle, asking him to verify. Galle found Neptune in the same night he received Le Verrier's letter, within 1° of the predicted position. The discovery of Neptune is widely regarded as a dramatic validation of celestial mechanics, and is one of the most remarkable moments of 19th-century science.

A geocentric orbit, Earth-centered orbit, or Earth orbit involves any object orbiting Earth, such as the Moon or artificial satellites. In 1997, NASA estimated there were approximately 2,465 artificial satellite payloads orbiting Earth and 6,216 pieces of space debris as tracked by the Goddard Space Flight Center. More than 16,291 objects previously launched have undergone orbital decay and entered Earth's atmosphere.

In astrodynamics and aerospace, a delta-v budget is an estimate of the total change in velocity (delta-v) required for a space mission. It is calculated as the sum of the delta-v required to perform each propulsive maneuver needed during the mission. As input to the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, it determines how much propellant is required for a vehicle of given empty mass and propulsion system.

In spaceflight, an orbital maneuver is the use of propulsion systems to change the orbit of a spacecraft. For spacecraft far from Earth an orbital maneuver is called a deep-space maneuver (DSM).

The Hiten spacecraft, given the English name Celestial Maiden and known before launch as MUSES-A, part of the MUSES Program, was built by the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science of Japan and launched on January 24, 1990. It was Japan's first lunar probe, the first robotic lunar probe since the Soviet Union's Luna 24 in 1976, and the first lunar probe launched by a country other than the Soviet Union or the United States. The spacecraft was named after flying heavenly beings in Buddhism.

Ewen Adair Whitaker was a British-born astronomer who specialized in lunar studies. During World War II he was engaged in quality control for the lead sheathing of hollow cables strung under the English Channel as part of the "Pipe Line Under The Ocean" Project (PLUTO) to supply gasoline to Allied military vehicles in France. After the war, he obtained a position at the Royal Greenwich Observatory working on the UV spectra of stars, but became interested in lunar studies. As a sideline, Whitaker drew and published the first accurate chart of the South Polar area of the Moon in 1954, and served as director of the Lunar Section of the British Astronomical Association.

Vladimir Petrovich Vetchinkin was a Soviet scientist in the field of aerodynamics, aeronautics, and wind energy, Doctor of Technical Sciences (1927), Honored Science Worker of the RSFSR (1946).

A low-energy transfer, or low-energy trajectory, is a route in space that allows spacecraft to change orbits using significantly less fuel than traditional transfers. These routes work in the Earth–Moon system and also in other systems, such as between the moons of Jupiter. The drawback of such trajectories is that they take longer to complete than higher-energy (more-fuel) transfers, such as Hohmann transfer orbits.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to space exploration.

Palm Heinrich Ludwig (Pruß) von Boguslawski was a German astronomy professor and observatory director in Breslau (Wrocław).

A halo orbit is a periodic, three-dimensional orbit associated with one of the L1, L2 or L3 Lagrange points in the three-body problem of orbital mechanics. Although a Lagrange point is just a point in empty space, its peculiar characteristic is that it can be orbited by a Lissajous orbit or by a halo orbit. These can be thought of as resulting from an interaction between the gravitational pull of the two planetary bodies and the Coriolis and centrifugal force on a spacecraft. Halo orbits exist in any three-body system, e.g., a Sun–Earth–orbiting satellite system or an Earth–Moon–orbiting satellite system. Continuous "families" of both northern and southern halo orbits exist at each Lagrange point. Because halo orbits tend to be unstable, station-keeping using thrusters may be required to keep a satellite on the orbit.

Ary Sternfeld was co-creator of the modern aerospace science. He was a Polish engineer of Jewish origin, who studied in Poland and France. From 1935 until his death he worked in Moscow.

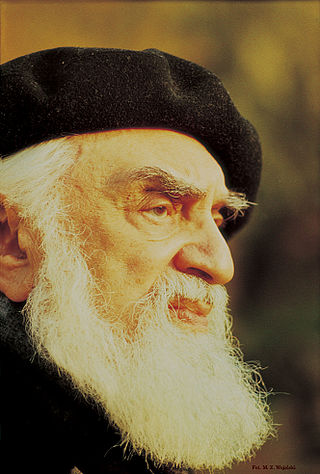

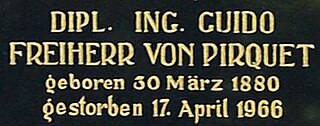

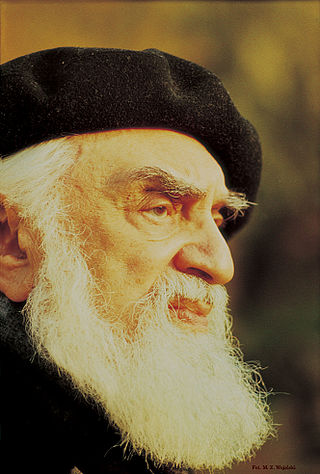

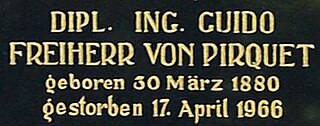

Guido von Pirquet was an Austrian pioneer of astronautics and a Baron of a lower noble family.

Chang'e 5-T1 was an experimental robotic spacecraft that was launched to the Moon on 23 October 2014, by the China National Space Administration (CNSA) to conduct atmospheric re-entry tests on the capsule design planned to be used in the Chang'e 5 mission. As part of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program, Chang'e 5, launched in 2020, was a Moon sample return mission. Like its predecessors, the spacecraft is named after the Chinese Moon goddess Chang'e. The craft consisted of a return vehicle capsule and a service module orbiter.