Related Research Articles

Hubert Walter was an influential royal adviser in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries in the positions of Chief Justiciar of England, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lord Chancellor. As chancellor, Walter began the keeping of the Charter Roll, a record of all charters issued by the chancery. Walter was not noted for his holiness in life or learning, but historians have judged him one of the most outstanding government ministers in English history.

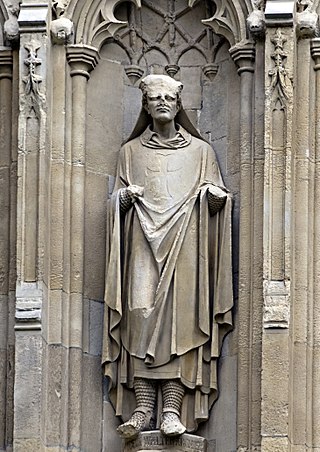

Aymer de Valence, 2nd Earl of Pembroke was an Anglo-French nobleman. Though primarily active in England, he also had strong connections with the French royal house. One of the wealthiest and most powerful men of his age, he was a central player in the conflicts between Edward II of England and his nobility, particularly Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster. Pembroke was one of the Lords Ordainers appointed to restrict the power of Edward II and his favourite Piers Gaveston. His position changed with the great insult he suffered when Gaveston, as a prisoner in his custody whom he had sworn to protect, was removed and beheaded at the instigation of Lancaster. This led Pembroke into close and lifelong cooperation with the king. Later in life, however, political circumstances combined with financial difficulties would cause him problems, driving him away from the centre of power.

Walter de Coutances was a medieval Anglo-Norman bishop of Lincoln and archbishop of Rouen. He began his royal service in the government of Henry II, serving as a vice-chancellor. He also accumulated a number of ecclesiastical offices, becoming successively canon of Rouen Cathedral, treasurer of Rouen, and archdeacon of Oxford. King Henry sent him on a number of diplomatic missions and finally rewarded him with the bishopric of Lincoln in 1183. He did not remain there long, for he was translated to Rouen in late 1184.

Leiston Abbey outside the town of Leiston, Suffolk, England, was a religious house of Canons Regular following the Premonstratensian rule, dedicated to St Mary. Founded in c. 1183 by Ranulf de Glanville, Chief Justiciar to King Henry II (1180-1189), it was originally built on a marshland isle near the sea, and was called "St Mary de Insula". Around 1363 the abbey suffered so much from flooding that a new site was chosen and it was rebuilt further inland for its patron, Robert de Ufford, 1st Earl of Suffolk (1298-1369). However, there was a great fire in c. 1379 and further rebuilding was necessary.

Vale Royal Abbey is a former medieval abbey and later country house in Whitegate, England. The precise location and boundaries of the abbey are difficult to determine in today's landscape. The original building was founded c. 1270 by the Lord Edward, later Edward I, for Cistercian monks. Edward had supposedly taken a vow during a rough sea crossing in the 1260s. Civil wars and political upheaval delayed the build until 1272, the year he inherited the throne. The original site at Darnhall was unsatisfactory, so was moved a few miles north to the Delamere Forest. Edward intended the structure to be on a grand scale—had it been completed it would have been the largest Cistercian monastery in the country—but his ambitions were frustrated by recurring financial difficulties.

Sir Richard de Exeter was an Anglo-Norman knight and baron who served as a judge in Ireland.

Walter de Luci, Abbot of Battle Abbey, was the brother of Richard de Luci, who was Chief Justiciar of England.

Darnhall Abbey was a late-thirteenth century Cistercian abbey at Darnhall, Cheshire, founded by Lord Edward sometime in the years around 1270. This was in thanks, so tells the Abbey's chronicler, for God saving him and his fleet from a storm at sea. It was dedicated to St Mary. It only existed for a short time before it moved to the better-known Vale Royal Abbey. The site chosen for the Abbey at Darnhall was discovered to be unfit for its purpose. Money was short, as Edward did not provide enough for the original foundation, but the Abbey was allowed to trade wool to augment its finances. The Abbey relocated a few miles north, and what remained of Darnhall Abbey became the monastic grange of the new foundation. There was probably only ever one Abbot of Darnhall before the Abbey relocated in 1275.

Thomas Kirkham was a pre-Reformation ecclesiastic notable for his role as the Bishop of Sodor and Man during the latter half of the 15th century.

In the early fourteenth century, tensions between villagers from Darnhall and Over, Cheshire, and their feudal lord, the Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, erupted into violence over whether they had villein—that is, servile—status. The villagers argued not, while the Abbey believed it was due the villagers' feudal service.

Stephen, was a late 14th-century abbot of Vale Royal Abbey in Cheshire. He is believed to have been born c. 1346, and in office from 27 January 1373 to possibly 1400, although the precise date of his departure is unknown. One of the earliest mentions of him as Abbot is 1373, when he received the homage of Robert Grosvenor for the manor of Lostock. He witnessed a charter between the prior of the Augustinian hermits in Warrington and the convent there in 1379. A few years later, Abbot Stephen provided evidence for the Royal Commission that was enquiring into the case of Scrope v Grosvenor, which sat for three years, concluding its business in 1389.

John Chaumpeneys was the last Abbot of Darnhall Abbey and first Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, Cheshire, from around 1275 to circ 1289.

John of Hoo was an early fourteenth-century Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, Cheshire. His abbacy was from around 1308–09 to 1314–15.

Richard of Evesham was Abbot of Vale Royal from 1316 to 1342.

Peter was an English Cistercian abbot who served as the fifth abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, Cheshire, in the first half of the 14th century. He is generally held to be the author of the abbey's own chronicle, which was published in 1914 as the Ledger of Vale Royal Abbey. Owing to a failure to finish the abbey's building works—which had commenced in 1277 and had been intermittently ongoing ever since—the abbey was unsightly, and the monks' quarters probably near derelict. Abbot Peter oversaw the transplantation of the house onto new grounds. Much of his career, however, was focussed on defending his abbey's feudal lordship over its tenants. The dispute between the abbey and its tenantry had existed since the abbey's foundation; the abbot desired to enforce his feudal rights, the serfs to reject them, as they claimed to be by then freemen. This did not merely involve Abbot Peter defending the privileges of his house in the courts. Although there was much litigation, with Abbot Peter having to defend himself to the Justice of Chester and even the King on occasion, by 1337 his discontented villagers even followed him from Cheshire to Rutland. A confrontation between Abbot Peter and his tenants resulted in the death of a monastic servant and his own capture and imprisonment. With the King's intervention, however, Abbot Peter and his party were soon freed.

Robert de Cheyneston was Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, Cheshire between 1340 and 1349. De Cheyneston had already been a monk at the Abbey before his election as Abbot.

Thomas Ragon was the eighth Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, Cheshire. His term of office lasted from 1351 to 1369. His abbacy was predominantly occupied with recommencing the building works at Vale Royal—which had been in abeyance for a decade—and the assertion of his abbey's rights over a satellite church in Llanbadarn Fawr, Ceredigion, which was also claimed by the Abbot of Gloucester.

John was Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, Cheshire, between 1405 and 1411, and although his abbacy seems to have been largely free of the local disorder that had plagued those of his predecessors, the Abbey appears to have been taken in to King Henry IV's hands on at least two occasions.

Vale Royal Abbey is a medieval abbey, and later a country house, located in Whitegate, between Northwich and Winsford in Cheshire, England. During its 278-year period of operation, it had at least 21 abbots.

John de Ponz, also called John de Ponte, John Savan, or John of Bridgwater (c.1248–1307) was an English-born administrator, lawyer and judge in the reign of King Edward I. He served in the Royal Household in England for several years before moving to Ireland, where he practised in the Royal Courts as the King's Serjeant-at-law (Ireland). He later served as a justice in eyre, and then as a justice of the Court of Common Pleas (Ireland). He was a gifted lawyer, but as a judge was accused of acting unjustly. A case he heard in Kilkenny in 1302 can be seen as a precursor of the Kilkenny Witchcraft Trials of 1324, and involved several of the main actors in the Trials.

References

- ↑ Heale 2016, p. 91.

- ↑ Brownbill 1914, p. 20.

- ↑ Brownbill 1914, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 V. C. H. 1980, pp. 156–65.

- ↑ Given-Wilson et al. 2005.

- ↑ Sayles 1988, p. 253.

- ↑ Baines 1836, pp. 378–79.

- ↑ Denton 1992, p. 131.

- 1 2 Brownbill 1914, pp. 20–23.

- ↑ Brownbill 1914, p. 14.

- ↑ Smith & London 2001, p. 317.

Bibliography

- Baines, E. (1836). History of the County Palatine and Duchy of Lancaster. Vol. IV. London: Fisher, son & Company.

- Brownbill, J., ed. (1914). The Ledger Book of Vale Royal Abbey. Manchester: Manchester Record Society.

- Denton, J. (1992). "From the Foundation of Vale Royal Abbey to the Statute of Carlisle: Edward I and Ecclesiastical Patronage". In P. R. Coss (ed.). Thirteenth Century England IV: Proceedings of the Newcastle Upon Tyne Conference 1991. Thirteenth Century England. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85115-325-4.

- Given-Wilson, C.; Brand, P.; Phillips, S.; Ormrod, M.; Martin, G.; Curry, A.; Horrox, R., eds. (2005). "'Edward I: Summer, 1302'" . British History Online. Parliament Rolls of Medieval England. Woodbridge.

- Heale, M. (2016). The Abbots and Priors of Late Medieval and Reformation England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870253-5.

- Sayles, G. O. (1988). The Functions of the Medieval Parliament of England. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-0-907628-92-7.

- Smith, C. M.; London, V. C. M. (2001). The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales, 1216–1377. Vol. II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-42892-7.

- V. C. H. (1980). Elrington, C. R.; Harris, B. E. (eds.). "Houses of Cistercian monks: The abbey of Vale Royal". Victoria County History. A History of the County of Chester, III. London.