Rievaulx Abbey was a Cistercian abbey in Rievaulx, near Helmsley, in the North York Moors National Park, North Yorkshire, England. It was one of the great abbeys in England until it was seized in 1538 under Henry VIII during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The wider site was awarded Scheduled Ancient Monument status in 1915 and the abbey was brought into the care of the then Ministry of Works in 1917. The ruins of its main buildings are today a tourist attraction, owned and maintained by English Heritage.

Theobald of Bec was a Norman archbishop of Canterbury from 1139 to 1161. His exact birth date is unknown. Some time in the late 11th or early 12th century Theobald became a monk at the Abbey of Bec, rising to the position of abbot in 1137. King Stephen of England chose him to be Archbishop of Canterbury in 1138. Canterbury's claim to primacy over the Welsh ecclesiastics was resolved during Theobald's term of office when Pope Eugene III decided in 1148 in Canterbury's favour. Theobald faced challenges to his authority from a subordinate bishop, Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester and King Stephen's younger brother, and his relationship with King Stephen was turbulent. On one occasion Stephen forbade him from attending a papal council, but Theobald defied the king, which resulted in the confiscation of his property and temporary exile. Theobald's relations with his cathedral clergy and the monastic houses in his archdiocese were also difficult.

Croxden Abbey, also known as "Abbey of the Vale of St. Mary at Croxden", was a Cistercian abbey at Croxden, Staffordshire, United Kingdom. A daughter house of the abbey in Aunay-sur-Odon, Normandy, the abbey was founded by Bertram III de Verdun of Alton Castle, Staffordshire, in the 12th century. The abbey was dissolved in 1538.

St Mary's Abbey, Melrose is a partly ruined monastery of the Cistercian order in Melrose, Roxburghshire, in the Scottish Borders. It was founded in 1136 by Cistercian monks at the request of King David I of Scotland and was the chief house of that order in the country until the Reformation. It was headed by the abbot or commendator of Melrose. Today the abbey is maintained by Historic Environment Scotland as a scheduled monument.

Buildwas Abbey was a Cistercian monastery located on the banks of the River Severn, at Buildwas in Shropshire, England - today about 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Ironbridge. Founded by the local bishop in 1135, it was sparsely endowed at the outset but enjoyed several periods of growth and increasing wealth: notably under Abbot Ranulf in the second half of the 12th century and again from the mid-13th century, when large numbers of acquisitions were made from the local landed gentry. Abbots were regularly used as agents by the Plantagenet monarchs in their attempts to subdue Ireland and Wales and the abbey acquired a daughter house in each country.

Aldringham cum Thorpe is a civil parish in the East Suffolk district of Suffolk, England. Located south of the town of Leiston, the parish includes the villages of Aldringham and Thorpeness, which is on the coast, between Sizewell (north) and Aldeburgh (south). In 2007 it had an estimated population of 700, rising to 759 at the 2011 Census.

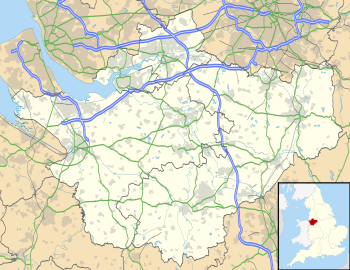

Darnhall is a civil parish and small village to the south west of Winsford in the Borough of Cheshire West and Chester and the ceremonial county of Cheshire in England. It had a population of 232 at the 2011 Census.

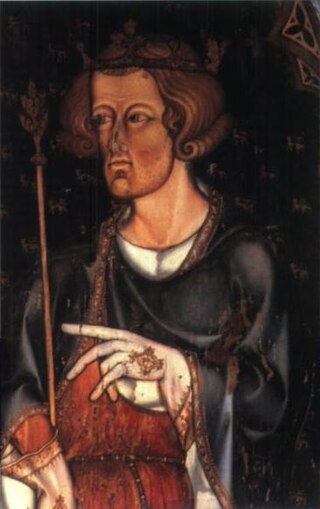

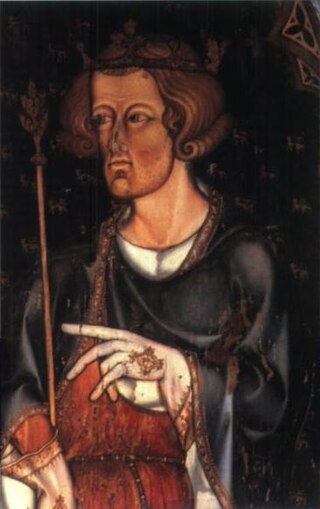

Vale Royal Abbey is a former medieval abbey and later country house in Whitegate, England. The precise location and boundaries of the abbey are difficult to determine in today's landscape. The original building was founded c. 1270 by the Lord Edward, later Edward I, for Cistercian monks. Edward had supposedly taken a vow during a rough sea crossing in the 1260s. Civil wars and political upheaval delayed the build until 1272, the year he inherited the throne. The original site at Darnhall was unsatisfactory, so was moved a few miles north to the Delamere Forest. Edward intended the structure to be on a grand scale—had it been completed it would have been the largest Cistercian monastery in the country—but his ambitions were frustrated by recurring financial difficulties.

Saint Padarn's Church is a parish church of the Church in Wales, and the largest mediaeval church in mid-Wales. It is at Llanbadarn Fawr, near Aberystwyth, in Ceredigion, Wales.

Darnhall Abbey was a late-thirteenth century Cistercian abbey at Darnhall, Cheshire, founded by Lord Edward sometime in the years around 1270. This was in thanks, so tells the Abbey's chronicler, for God saving him and his fleet from a storm at sea. It was dedicated to St Mary. It only existed for a short time before it moved to the better-known Vale Royal Abbey. The site chosen for the Abbey at Darnhall was discovered to be unfit for its purpose. Money was short, as Edward did not provide enough for the original foundation, but the Abbey was allowed to trade wool to augment its finances. The Abbey relocated a few miles north, and what remained of Darnhall Abbey became the monastic grange of the new foundation. There was probably only ever one Abbot of Darnhall before the Abbey relocated in 1275.

In the early fourteenth century, tensions between villagers from Darnhall and Over, Cheshire, and their feudal lord, the Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, erupted into violence over whether they had villein—that is, servile—status. The villagers argued not, while the Abbey believed it was due the villagers' feudal service.

Stephen, was a late 14th-century abbot of Vale Royal Abbey in Cheshire. He is believed to have been born c. 1346, and in office from 27 January 1373 to possibly 1400, although the precise date of his departure is unknown. One of the earliest mentions of him as Abbot is 1373, when he received the homage of Robert Grosvenor for the manor of Lostock. He witnessed a charter between the prior of the Augustinian hermits in Warrington and the convent there in 1379. A few years later, Abbot Stephen provided evidence for the Royal Commission that was enquiring into the case of Scrope v Grosvenor, which sat for three years, concluding its business in 1389.

John Chaumpeneys was the last Abbot of Darnhall Abbey and first Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, Cheshire, from around 1275 to circ 1289.

Walter of Hereford was a twelfth- and thirteenth-century Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey in Cheshire. He was Abbot from around 1294 to approximately 1307. His abbacy occurred at a time of tribulation for the abbey, mostly due to poor relations with the local populace. Walter is in portrayed in his Abbey's later chronicler in superlatives. He is described as "greatly venerable in life and always and everywhere devoted to God and the Blessed Virgin Mary" and as

A man of most beautiful appearance, as regards externals...and in good works also he fought a good fight for Christ, for he used a hair shirt to conquer the flesh, and by this discipline subdued it to the spirit. He rarely or never ate meat.

John of Hoo was an early fourteenth-century Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, Cheshire. His abbacy was from around 1308–09 to 1314–15.

Richard of Evesham was Abbot of Vale Royal from 1316 to 1342.

Robert de Cheyneston was Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, Cheshire between 1340 and 1349. De Cheyneston had already been a monk at the Abbey before his election as Abbot.

Thomas Ragon was the eighth Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, Cheshire. His term of office lasted from 1351 to 1369. His abbacy was predominantly occupied with recommencing the building works at Vale Royal—which had been in abeyance for a decade—and the assertion of his abbey's rights over a satellite church in Llanbadarn Fawr, Ceredigion, which was also claimed by the Abbot of Gloucester.

John was Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, Cheshire, between 1405 and 1411, and although his abbacy seems to have been largely free of the local disorder that had plagued those of his predecessors, the Abbey appears to have been taken in to King Henry IV's hands on at least two occasions.

Vale Royal Abbey is a medieval abbey, and later a country house, located in Whitegate, between Northwich and Winsford in Cheshire, England. During its 278-year period of operation, it had at least 21 abbots.