Related Research Articles

Chiang Kai-shek was a Chinese statesman, revolutionary, and military commander. He was the head of the Nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) party, General of the National Revolutionary Army, known as Generalissimo, and the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) in mainland China from 1928 until 1949. After being defeated in the Chinese Civil War by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1949, he led the ROC on the island of Taiwan until his death in 1975.

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and the forces of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), with armed conflict continuing intermittently from 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949, resulting in a CCP victory and control of mainland China in the Chinese Communist Revolution.

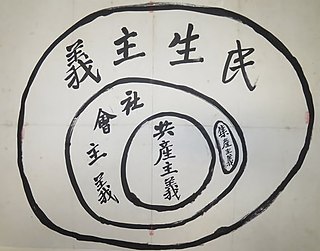

Chinese nationalism is a form of nationalism in which asserts that the Chinese people are a nation and promotes the cultural and national unity of all Chinese people. According to Sun Yat-sen's philosophy in the Three Principles of the People, Chinese nationalism is evaluated as multi-ethnic nationalism, which should be distinguished from Han nationalism or local ethnic nationalism.

The Xi'an Incident was a major Chinese political crisis from 12 to 26 December 1936. Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Nationalist government of China, was placed under house arrest in the city of Xi'an by a Nationalist army he was there to review. Chiang's captors hoped to end the Chinese Civil War and confront Japanese imperial expansion into Chinese territory. After two weeks of intense negotiations between Chiang, his captors, and representatives of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Chiang was released with a verbal promise to end the civil war and put up a firmer resistance to Japan.

Patrick Jay Hurley was an American politician and diplomat. He was the United States Secretary of War from 1929 to 1933, but is best remembered for being Ambassador to China in 1945, during which he was instrumental in getting Joseph Stilwell recalled from China and replaced with the more diplomatic General Albert Coady Wedemeyer. A man of humble origins, Hurley's lack of what was considered to be a proper ambassadorial demeanor and mode of social interaction made professional diplomats scornful of him. He came to share pre-eminent army strategist Wedemeyer's view that the Chinese Communists could be defeated and America ought to commit to doing so even if it meant backing the Kuomintang and Chiang Kai-shek to the hilt. Frustrated, Hurley resigned as Ambassador to China in 1945, publicised his concerns about high-ranking members of the State Department, and alleged they believed that the Chinese Communists were not totalitarians and that America's priority was to avoid allying with a losing side in the civil war.

Operation Ichi-Go was a campaign of a series of major battles between the Imperial Japanese Army forces and the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China, fought from April to December 1944. It consisted of three separate battles in the Chinese provinces of Henan, Hunan and Guangxi.

The Liaoshen campaign, an abbreviation of Liaoning–Shenyang campaign after the province of Liaoning and its Yuan directly administered capital city Shenyang, was the first of the three major military campaigns launched by the Communist People's Liberation Army (PLA) against the Kuomintang Nationalist government during the late stage of the Chinese Civil War. This engagement is also known to the Kuomintang as the Liaohsi campaign, and took place between September and November 1948, lasting a total of 52 days. The campaign ended after the Nationalist forces suffered sweeping defeats across Manchuria, losing the major cities of Jinzhou, Changchun, and eventually Shenyang in the process, leading to the capture of the whole of Manchuria by the Communist forces. The victory of the campaign resulted in the Communists achieving a strategic numerical advantage over the Nationalists for the first time in its history.

Wei Lihuang was a Chinese general who served the Nationalist government throughout the Chinese Civil War and Second Sino-Japanese War as one of China's most successful military commanders.

The Nationalist government, officially the National Government of the Republic of China, refers to the government of the Republic of China from 1 July 1925 to 20 May 1948, led by the nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) party.

Zhang Zhizhong or Chang Chih-chung was a Chinese military commander and politician, general in the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China and later a pro-Communist politician in the People's Republic of China.

Hu Zongnan, courtesy name Shoushan (壽山), was a Chinese general in the National Revolutionary Army and then the Republic of China Army. Together with Chen Cheng and Tang Enbo, Hu, a native of Zhenhai, Ningbo, formed the triumvirate of Chiang Kai-shek's most trusted generals during the Second Sino-Japanese War. After the retreat of the Nationalists to Taiwan in 1949, he also served as the President's military strategy advisor until his death in 1962.

The Second United Front was the alliance between the ruling Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to resist the Japanese invasion of China during the Second Sino-Japanese War, which suspended the Chinese Civil War from 1937 to 1945.

The Shanghai massacre of 12 April 1927, the April 12 Purge or the April 12 Incident as it is commonly known in China, was the violent suppression of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) organizations and leftist elements in Shanghai by forces supporting General Chiang Kai-shek and conservative factions in the Kuomintang. Following the incident, conservative KMT elements carried out a full-scale purge of communists in all areas under their control, and violent suppression occurred in Guangzhou and Changsha. The purge led to an open split between left-wing and right-wing factions in the KMT, with Chiang Kai-shek establishing himself as the leader of the right-wing faction based in Nanjing, in opposition to the original left-wing KMT government based in Wuhan, which was led by Wang Jingwei. By 15 July 1927, the Wuhan regime had expelled the Communists in its ranks, effectively ending the First United Front, a working alliance of both the KMT and CCP under the tutelage of Comintern agents. For the rest of 1927, the CCP would fight to regain power, beginning the Autumn Harvest Uprising. With the failure and the crushing of the Guangzhou Uprising at Guangzhou however, the power of the Communists was largely diminished, unable to launch another major urban offensive.

The historical Kuomintang socialist ideology is a form of socialist thought developed in mainland China during the early Republic of China. The Tongmenghui revolutionary organization led by Sun Yat-sen was the first to promote socialism in China.

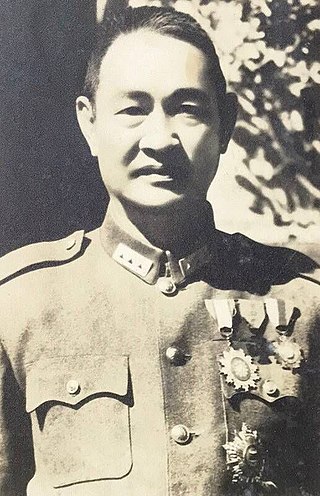

Cheng Qian was a Chinese army officer and politician who held very important military and political positions in both the Republic of China and the People's Republic of China. Educated at the Imperial Japanese Army Academy and Waseda University, he first met Sun Yat-sen in Tokyo, becoming an early supporter. Later, under Chiang Kai-shek, he was one of the most powerful members of the Kuomintang, notably serving as Chief of Staff of the Military Affairs Commission during the Second Sino–Japanese War.

The Chinese Communist Revolution was a social and political revolution that culminated in the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. For the preceding century, China had faced escalating social, economic, and political problems as a result of Western imperialism, Japanese imperialism, and the decline of the Qing dynasty. Cyclical famines and an oppressive landlord system kept the large mass of rural peasantry poor and politically disenfranchised. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was formed in 1921 by young urban intellectuals inspired by European socialist ideas and the success of the October Revolution in Russia. The CCP originally allied itself with the nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) party against the warlords and foreign imperialist forces, but the 1927 massacre of Communists in Shanghai ordered by Kuomintang leader Chiang Kai-shek forced them into the Chinese Civil War, which would last more than three decades.

Zheng Dongguo was a field commander in the Republic of China National Revolutionary Army. He took part in the Second Sino-Japanese War, and was active in southern China and in the Burma theatre of the war, drawing troops from Yunnan. After the Japanese surrender in 1945, he was an important commander in the Chinese Civil War serving under Du Yuming and Chen Cheng in Manchuria.

The Chongqing Negotiations were a series of negotiations between the Kuomintang-ruled Nationalist government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 29 August to 10 October 1945, held in Chongqing, China. The negotiations were highlighted by the final meeting between the leaders of both parties, Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong, which was the first time they had met in 20 years. Most of the negotiations were undertaken by Wang Shijie and Zhou Enlai, representatives of the Nationalist government and CCP, respectively. The negotiations lasted for 43 days, and came to a conclusion after both parties signed the Double Tenth Agreement.

The Wuhan Nationalist government, also known as the Wuhan government, Wuhan regime, or Hankow government, was a government dominated by the left-wing of the Nationalist or Kuomintang (KMT) Party of China that was based in Wuhan from 5 December 1926 to 21 September 1927, led first by Eugene Chen, and later by Wang Jingwei.

Chiangism, also known as the Political Philosophy of Chiang Kai-shek, or Chiang Kai-shek Thought, is the political philosophy of President Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, who used it during his rule in China under the Kuomintang on both the mainland and Taiwan. It is a right-wing authoritarian nationalist political ideology which is based on mostly Confucian and Tridemist ideologies, and was used in the New Life Movement in China and the Chinese Cultural Renaissance movement in Taiwan. It is a syncretic mix of many political ideologies, including revolutionary nationalism, Tridemism, socialism, militarism, Confucianism, state capitalism, constitutionalism, fascism, authoritarian capitalism, and paternalistic conservatism, as well as Chiang's Methodist Christian beliefs.

References

- ↑ Brady, Anne-Marie (2003). Making the Foreign Serve China: Managing Foreigners in the People's Republic. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 46,47. ISBN 0742518612.

- ↑ Hamilton, John M., Edgar Snow: A Biography, LSU Press, (2003) ISBN 0-8071-2912-7, ISBN 978-0-8071-2912-8, p. 167; Shewmaker, Kenneth E., Americans and Chinese Communists, 1927-1945: A Persuading Encounter, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press (1971) ISBN 0-8014-0617-X

- ↑ Kenneth E. Shewmaker, "The "Agrarian Reformer" Myth," The China Quarterly 34 (1968): 66-81.

- ↑ John Service, Report No. 5, 8 March 1944, to Commanding General Fwd. Ech., USAF – CBI, APO 879. "The Communist Policy Towards the Kuomintang." State Department, NARA, RG 59.

- ↑ U.S. Congress. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and the Other Internal Security Laws. The Amerasia Papers: A Clue to the Catastrophe of China. Vol. 1 (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1970), 406 – 407.

- ↑ Fenby, Jonathan Chiang Kai-shek China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost, New York: Carrol & Graf, 2004 page 424.

- 1 2 3 Taylor, Jay (209). The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China. Harvard University Press. p. 297,298. ISBN 0674054717.

- ↑ Russel D. Buhite, Patrick J. Hurley and American Foreign Policy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell U Press, 1973), 160 – 162.

- ↑ Wesley Marvin Bagby, The Eagle-Dragon Alliance: America's Relations with China in World War II, p.96

- ↑ Fenby, Jonathan Chiang Kai-shek China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost, New York: Carrol & Graf, 2004 page 438.

- ↑ ——— (2004). Stalin: A Biography. London: Macmillan. p. 553. ISBN 978-0-333-72627-3.

- ↑ Helen Rappaport (1999). Joseph Stalin: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. p. 36. ISBN 9781576070840.

- ↑ Chalmers A. Johnson (1962). Peasant Nationalism and Communist Power: The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1937-1945. Stanford University Press. pp. 15–19. ISBN 0804700745.

- ↑ Chalmers A. Johnson (1962). Peasant Nationalism and Communist Power: The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1937-1945. Stanford University Press. pp. 31, 47–49. ISBN 0804700745.

- ↑ Chalmers A. Johnson (1962). Peasant Nationalism and Communist Power: The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1937-1945. Stanford University Press. pp. 117, 139. ISBN 0804700745.

- ↑ Chalmers A. Johnson (1962). Peasant Nationalism and Communist Power: The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1937-1945. Stanford University Press. p. 143. ISBN 0804700745.

- ↑ Walter Theodore Hitchcock (1991). The Intelligence Revolution: A Historical Perspective : Proceedings of the Thirteenth Military History Symposium, U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colorado, October 12-14, 1988. U.S. Air Force Academy, Office of Air Force History, United States Air Force. pp. 213–215. ISBN 0912799706.