Connellsville is a city in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, United States, 50 miles (80 km) southeast of Pittsburgh on the Youghiogheny River, a tributary of the Monongahela River. It is part of the Pittsburgh Metro Area. The population was 7,637 at the 2010 census, down from 9,146 at the 2000 census.

The Interurban is a type of electric railway, with streetcar-like electric self-propelled rail cars which run within and between cities or towns. They were very prevalent in North America between 1900 and 1925 and were used primarily for passenger travel between cities and their surrounding suburban and rural communities. Interurban as a term encompassed the companies, their infrastructure, their cars that ran on the rails, and their service. In the United States, the early 1900s interurban was a valuable economic institution. Most roads between towns and many town streets were unpaved. Transportation and haulage was by horse-drawn carriages and carts. The interurban provided reliable transportation, particularly in winter weather, between the town and countryside. In 1915, 15,500 miles (24,900 km) of interurban railways were operating in the United States and, for a few years, interurban railways, including the numerous manufacturers of cars and equipment, were the fifth-largest industry in the country. By 1930, most interurbans in North America were gone with a few surviving into the 1950s. Oliver Jensen, author of American Heritage History of Railroads in America, commented that "...the automobile doomed the interurban whose private tax paying tracks could never compete with the highways that a generous government provided for the motorist."

The Philadelphia and Western Railroad was a high-speed, third rail-equipped, commuter-hauling interurban electric railroad operating in the western suburbs of the U.S. city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. One of its lines is now SEPTA's Norristown High Speed Line; the other has been abandoned. Part of the abandoned line within Radnor Township is now the Radnor Trail, a multi-use path or rail trail.

The Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad (P&LE), also known as the "Little Giant", was formed on May 11, 1875. Company headquarters were located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The line connected Pittsburgh in the east with Youngstown, Ohio at nearby Haselton, Ohio in the west and Connellsville, Pennsylvania to the east. It did not reach Lake Erie until the formation of Conrail in 1976. The P&LE was known as the "Little Giant" since the tonnage that it moved was out of proportion to its route mileage. While it operated around one tenth of one percent of the nation's railroad miles, it hauled around one percent of its tonnage. This was largely because the P&LE served the steel mills of the greater Pittsburgh area, which consumed and shipped vast amounts of materials. It was a specialized railroad deriving much of its revenue from coal, coke, iron ore, limestone, and steel. The eventual closure of the steel mills led to the end of the P&LE as an independent line in 1992.

The Southwest Pennsylvania Railroad is a shortline railroad that operates in southwestern Pennsylvania. The SWP uses rail branches that were acquired from CSX Transportation and Conrail. All of the track used by the SWP is in either Fayette or Westmoreland counties. SWP provides local service to many customers in the area, connecting them to the outside world via interchanges with Norfolk Southern, Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad, and CSX. SWP has been vital in the location of several new industries to Fayette and Westmoreland Counties in recent years.

Route 15, the Girard Avenue Line, is a trolley line operated by the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) along Girard Avenue through North and West Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. As of 2007, it is the only surface trolley line in the City Transit Division that is not part of the Subway–Surface Trolley Lines. SEPTA PCC II vehicles are used on the line.

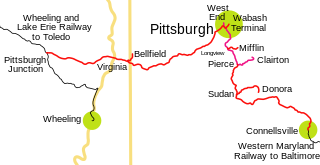

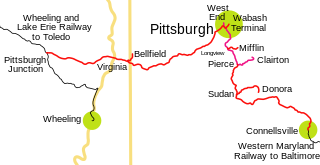

The Pittsburgh and West Virginia Railway was a railroad in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Wheeling, West Virginia, areas. Originally built as the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway, a Pittsburgh extension of George J. Gould's Wabash Railroad, the venture entered receivership in 1908 and the line was cut loose. An extension completed in 1931 connected it to the Western Maryland Railway at Connellsville, Pennsylvania, forming part of the Alphabet Route, a coalition of independent lines between the Northeastern United States and the Midwest. It was leased by the Norfolk and Western Railway in 1964 in conjunction with the N&W acquiring several other sections of the former Alphabet Route, but was leased to the new spinoff Wheeling and Lake Erie Railway in 1990, just months before the N&W was merged into the Norfolk Southern Railway.

The Sacramento Northern Railway was a 183-mile (295 km) electric interurban railway that connected Chico in northern California with Oakland via the California capital, Sacramento. In its operation it ran directly on the streets of Oakland, Sacramento, Yuba City, Chico, and Woodland and ran interurban passenger service until 1941 and freight service into the 1960s.

Pittsburgh Railways was one of the predecessors of the Port Authority of Allegheny County. It had 666 PCC cars, the third largest fleet in North America. It had 68 streetcar routes, of which only three are used by the Port Authority as light rail routes. With the Port Authority's Transit Development Plan, many route names will be changed to its original, such as the 41D Brookline becoming the 39 Brookline. Many of the streetcar routes have been remembered in the route names of many Port Authority buses.

Pittsburgh, surrounded by rivers and hills, has a unique transportation infrastructure that includes roads, tunnels, bridges, railroads, inclines, bike paths, and stairways.

The Union Railroad is a Class III switching railroad located in Allegheny County in Western Pennsylvania. The company is owned by Transtar, Inc., which is itself a subsidiary of USS Corp, more popularly known as United States Steel. The railroad's primary customers are the three plants of the USS Mon Valley Works, the USS Edgar Thomson Steel Works, the USS Irvin Works and the USS Clairton Works.

The Pennsylvania Trolley Museum, located at 1 Museum Road, Washington, Pennsylvania, is a museum dedicated to operation and preservation of streetcars and trolleys primarily from Pennsylvania, but their collection of historic trolleys includes examples from near by Toledo Ohio, New Orleans, and even an open sided car from Brazil. Many have been painstakingly restored to operating condition. Other unique cars either waiting for restoration or incompatible with the Pennsylvania trolley gauge track are on display in a massive trolley display building. Notable examples on static display include a J.G. Brill “brilliner” car which was introduced as a competitor to the PCC, locomotives, and a horse car from the early days of Pittsburgh’s public transit systems.

The Hagerstown & Frederick Railway, now defunct, was an American railroad of central Maryland built in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The 47D Drake was a PCC trolley line that was part of the Pittsburgh Light Rail system.

The Lehigh Valley Transit Company (LVT) was a regional transport company, headquartered in Allentown, Pennsylvania, that began operations in 1901 as an urban trolley and interurban rail transport company. It operated successfully into the 1930s, struggled financially during the Depression, and was saved from abandonment by a dramatic ridership increase due to the Second World War. In 1951, the LVT, once again financially struggling, ended its 36-mile (58 km) interurban rail service from Allentown to Philadelphia. In 1952, it ended its Allentown area local trolley service. It operated local bus service in the Allentown, Bethlehem, and Easton, Pennsylvania, areas until going out of business in 1972.

Conestoga Traction, later Conestoga Transportation Company, was a classic American regional interurban trolley that operated seven routes 1899 to 1946 radiating spoke-like from Lancaster, Pennsylvania to numerous neighboring farm villages and towns. It ran side-of-road trolleys through Amish farm country to Coatesville, Strasburg/Quarryville, Pequea, Columbia/Marietta, Elizabethtown, Manheim/Lititz, and Ephrata/Adamstown/Terre Hill.

U.S. Route 119 (US 119) travels through Connellsville, Greensburg, and Punxsutawney, and bypasses Uniontown and Indiana. There are numerous other boroughs and villages along its 133-mile (214 km) route in the Keystone State. The southern entrance of US 119 is at the West Virginia state line one-half-mile south of Point Marion. The northern terminus is at US 219 two miles (3 km) south of DuBois, Pennsylvania. US 119 is in the National Highway System from the West Virginia state line to Exit 0 of PA Turnpike 66, and from US 22 to US 219. From US 22 to US 219, the highway carries the name of the Buffalo-Pittsburgh Highway; from US 22 to PA 56, it is also known as the Patrick J. Stapleton Highway; near Uniontown, it bears the name George C. Marshall Parkway.

The Memorial Bridge is a structure that crosses the Youghiogheny River, connecting the eastern and western shores of Connellsville, Pennsylvania, USA.

The Colorado Springs and Interurban Railway was an electric trolley system in the Colorado Springs, Colorado that operated from 1902 to 1932. The company was formed when Winfield Scott Stratton purchased Colorado Springs Rapid Transit Railway in 1901 and consolidated it in 1902 with the Colorado Springs & Suburban Railway Company. It operated in Colorado Springs, its suburbs, and Manitou Springs. One of the street cars from Stratton's first order is listed on the Colorado State Register of Historic Properties.